The provision of non-medical prescribing in mental health services is not uniform; there is a mix of independent and supplementary prescribing which affects service provision and patients' access to medicines, leading to an inequity of treatment (Brimblecombe and Dobel-Ober, 2022).

The majority of prescribing in mental health in the UK takes place in community mental health in the UK takes place in community mental health teams, and drug and alcohol treatment services. New prescribers are introduced as independent prescribers where possible, and this is the preferred model to promote. The idea that non-medical prescribing can provide more effective and accessible healthcare for patients is the ethos that should be central to this promotion.

Non-medical prescribing can make it easier for patients to be seen by offering them a choice of care setting that is closer to their home. This can also provide greater potential for patients to engage with services as they have less distance to travel for treatment, and offer a more personalised level of care, with one-to-one sessions providing psychological interventions and a potential prescription for treatment at the end of the session.

Non-medical prescribing clinics can open up patients to some choice and there is a growing body of evidence to suggest that, where patients are given the opportunity to access non-medical prescribing specialist services, uptake is high with low did not attend rates (Ross, 2015).

Research suggests that prescribing by nurse practitioners in mental health settings can be well received by patients (Jones et al, 2007). The relationship can be more flexible and the patient's needs better met as the nurse practitioner can be more responsive to a patient then a psychiatrist in a clinical setting. Patients can be better accommodated in a non-medical prescribing setting then a doctor–patient relationship, and many find nurse prescribers easier to talk to and more responsive than doctors (Ross, 2015).

In other similar studies, patients highlighted some significant gains. They reported that nurse prescribing was more convenient and less anxiety provoking, an issue of particular importance for optimising mental health services. Offering choice was deemed important; however, for some service users, information about why medication may be beneficial was highlighted as an unmet need in the prescribing process. The practising nurse prescriber described their experiences and credited a good structure of supervision and support from the team (Gumber et al, 2011).

In terms of making prescribing safe for patients, recent studies in mental health have shown that nurse prescribing by either nurse consultants or experienced nurse practitioners can be safe and effective, and there is a high degree of compliance with the national standards set for prescribing. Often, the range of drugs prescribed can be narrow, but this idea of non-medical prescribing needs to be more widely used by the mental health sector.

The main areas where mental health services have non-medical prescribing in their area of expertise is in community mental health teams and drug and alcohol services. For drug services in primary care this has been expanded over the last few years, but has not been reflected in the expansion of non-medical prescribers in traditional mental health teams (Lowe et al, 2018). In these services, expansion of non-medical prescribing has been slow, and some psychiatrists and nurse prescribers have found some of the changes needed to accommodate this difficult to navigate (Brimblecombe and Dobel-Ober, 2022).

Non-medical prescribing is a relatively new competency in mental health services. However, there is a growing body of evidence that it appears to benefit both service users and health professionals alike (Ross et al, 2007; Brimblecombe and Dobel-Ober, 2022). Therefore, the promotion of this approach and its design is important to consider.

This article explores the area of alcohol dependency and depression, and some wider mental health issues in healthcare, illustrating how non-medical prescribers can manage patients with a more personalised and flexible approach. It highlights how this can work with GPs in primary care and mental health services in substance misuse to free up resources (Fernandez and Ryan, 2022). It is hoped this will encourage professionals in mental health services to promote the role of the non-medical prescriber for their services.

It is important for service managers to be aware of the value independent prescribers can bring and their relevance to improving healthcare (Furlong and Smith, 2005).

Alcohol and drug liaison service

The alcohol liaison service in an inner-London hospital has developed a nurse-led service model to meet the needs of the patient population it serves. Experienced non-medical prescribers deliver the service, and nurses are able to innovate and develop services tailored to patients' needs.

Traditional services for alcohol liaison have now become mainstream nationally, and the emphasis is to increase the coverage of the team to address the need for service provision, signposting and linking to community services. The team have been working on developing from this traditional model to deliver a more patient-centred service that can be used to prevent future admissions. It does this by providing a comprehensive service that can signpost and treat patients, and offer community prescribing and specialist advice through its outpatient service, which looks to treat patients who are resistant to mainstream alcohol services.

A growing problem recognised by the staff of the alcohol liaison service was frequent attenders to A&E and the hospital not engaging with local services. Therefore, staff were proactive in developing an outpatient service to engage and treat this cohort. During the assessment process, the patient is offered the opportunity to engage with the outpatient service. Recent data has shown this is a growing and significant number, with at least 33% of all assessed patients engaging with the outpatient service. The patients are offered:

- Motivational interviewing to improve a patient's insight into their dependency pattern

- Prescribing through non-medical function

- Prescribing through good links in primary care (long term)

- Comprehensive overview.

Patients have already experienced benefits from this approach to delivering an outpatient service for people with alcohol dependency. Many of those seen have been detoxed while in hospital and the role of the non-medical prescribing clinic was to enable patients to build on this, and try to maintain abstinence on discharge. On the whole, this has been achieved, with patients finding engagement with the clinic easy and quick access to medicines. It has been a responsive and proactive approach.

When patients detox, they often describe problems with low mood and depression. Often, the main trigger for patients is low mood, and alcohol is used to manage this, leading to dependent drinking. It is these patients the clinics have been able to assess and treat effectively, with non-medical prescribers having expertise in depression and alcohol, using informed prescribing to meet patient need.

Moderate-to-severe depression is often seen in patients in outpatient clinics, and the role of non-medical prescriber is integral to treating this cohort effectively. Alcohol dependency and depressive illnesses are highly prevalent, frequently co-occur and are associated with worse outcomes when paired. The assessment and treatment of patients with co-occurring alcohol use disorders and depressive illnesses is wrought with significant challenges (DeVido and Weiss, 2012). The non-medical prescribing clinic assesses and treats patients, prescribing an appropriate antidepressant to enable patients maintain abstinence.

Basic demographics

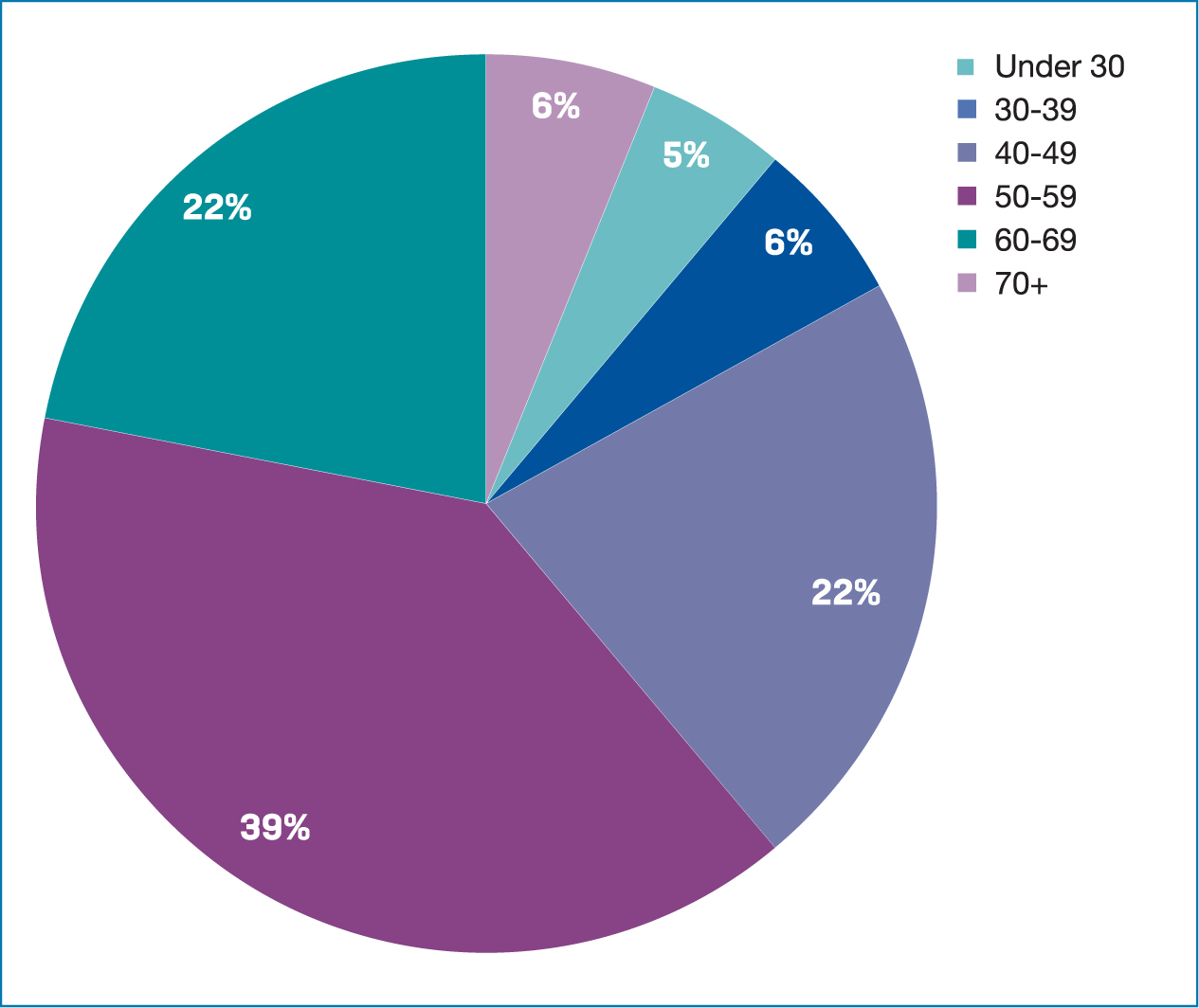

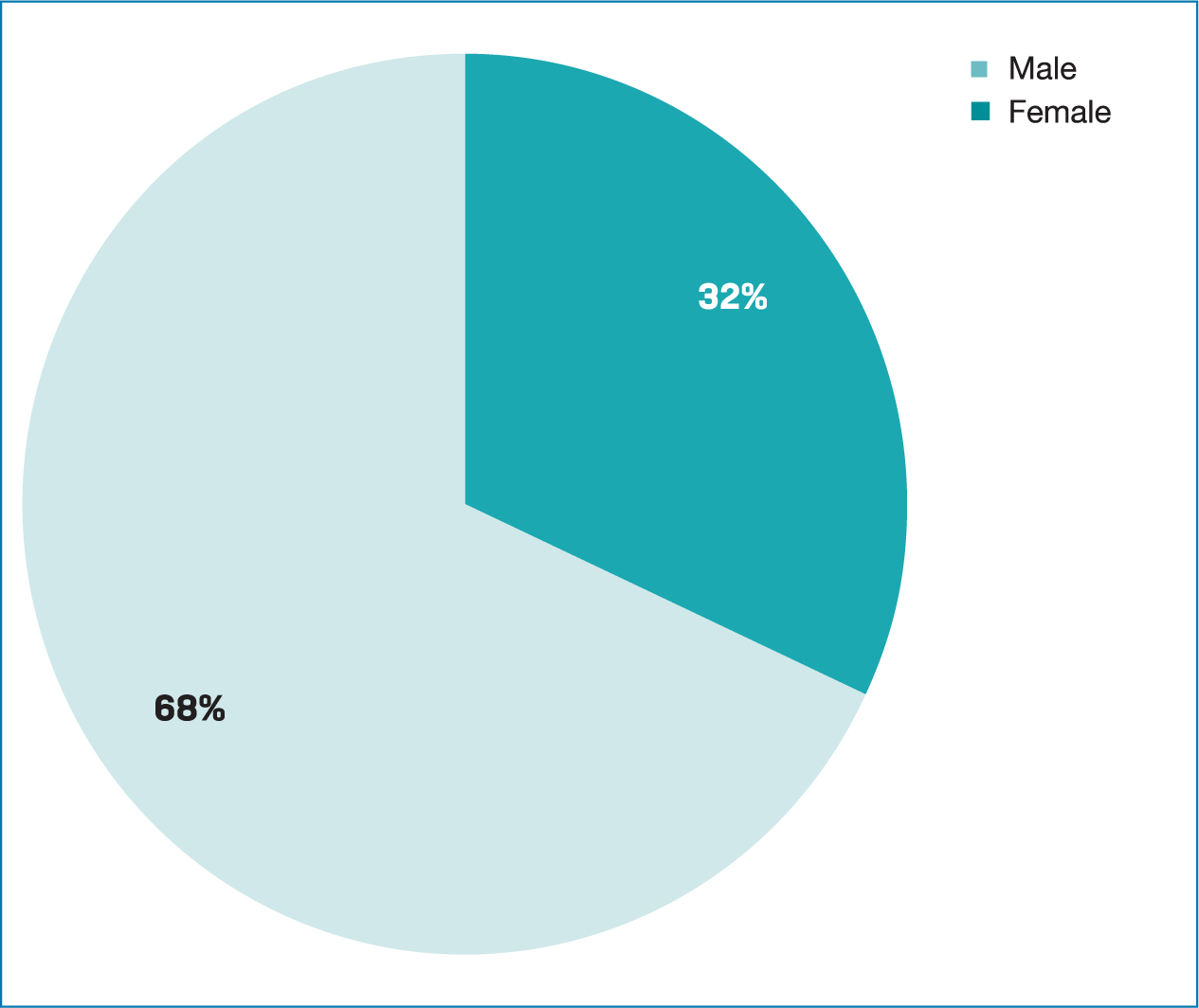

The number of patients seen in the outpatient clinic at the time of writing is 95. There are over 100 contacts and sessions conducted in outpatients to accommodate this (Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the age range and gender of this cohort).

The largest group of patients seen in the outpatient service is between 40 and 60 years old. Often, these patients have long-established dependent patterns on alcohol. This is similar to the picture seen in specialist alcohol services across the UK. The most common groups of patients are in the age range of 40–60 years old (Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, 2021). The population seen in the outpatient service are predominantly male, with a ratio of 3:1. This is greater than the gender ratio seen in national alcohol services, although this has varied marginally year to year.

Prescribing for depression

For patients with episodes of moderate or severe depression, combination therapy with an antidepressant and individual cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) should ideally be offered as first-line treatment. In some cases, and for people who have struggled with alcohol dependency, therapy with an antidepressant or a psychological treatment may also be offered as a first-line option.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) should be considered as the first choice of antidepressant treatment as they are well tolerated and have a good safety profile for patients. Other antidepressant options include serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), the main ones used in the field of alcohol dependency being mirtazapine and venlafaxine or an antidepressant based on the patient's previous treatment history, such as a tricyclic antidepressant. Tricylics should only be used if the non-medical prescriber has significant experience and expertise in the field (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2023).

When prescribing and starting an antidepressant medication, patients should be monitored every 2–4 weeks to ensure good practice and safe prescribing. NICE guidance is clear that monitoring and follow-up are important. When offering a person medication for the treatment of depression, discuss and agree a management plan with the person, which should include:

- The reasons for offering medication

- The choices of medication (if a number of different antidepressants are suitable)

- The dose, and how the dose may need to be adjusted

- The benefits, covering what improvements the person would like to see in their life and how the medication may help

- The harms, covering both the possible side effects and withdrawal effects, including any side effects they would particularly like to avoid (for example, weight gain, sedation, effects on sexual function)

- Any concerns they have about taking or stopping the medication.

This is part of the uniform approach the non-medical prescribers have for prescribing antidepressants in the outpatient clinic. The antidepressants commonly prescribed in the service are described below (NICE, 2023).

Sertraline

Used for moderate-to-severe depression. Initially 50 mg daily, then increased in steps of 50 mg at intervals of at least 1 week if required; maintenance 50 mg daily, maximum 200 mg per day. Used for patients who are reducing their alcohol intake or are abstinent.

Venlafaxine

Used for severe depression and anxiety, including social anxiety, generalised anxiety and panic disorder. The doses vary for each disorder and the patient should be fully assessed before medication is considered. This is used in the outpatient alcohol clinic for patients who have achieved abstinence and, as the case studies will show, this is achieved with good effect.

Mirtazapine

Used for major depression. Has a sedative effect and can be very useful for patients who struggle with a poor sleep pattern. Can also be good for patients who struggle with acute anxiety due to its sedative properties. Starting dose is 15 mg and the maximum dose is 45 mg. Patients on the medication should be reviewed even if it is used long term. In the outpatient alcohol clinic, patients who use alcohol to cope with a low mood and poor sleep pattern react well to this medication. They do also reduce their alcohol intake to manageable levels which ensures this can be prescribed for the long term (NICE, 2023).

Case studies

The following case studies outline the role of expert prescribing by experienced non-medical prescribers. Each describes the patients, their assessment process and the positive role effective prescribing can take to treat patients dependent on alcohol and suffering from depression. Case studies have been described as informative and educational (Yin, 2009), although critics have suggested they are unable to provide generalisations and therefore be more widely applicable (Silverman, 2014).

The case studies in this article show what is possible and the benefits for patients treated in the alcohol dependency field by non-medical prescribers. All names and details have been changed to maintain anonymity.

Carol

Carol had been admitted four times during the year 2022. Her most recent admission had been just before Christmas that year. She had a long and well-established alcohol dependency for many years. She was drinking due to being very anxious and, at times, she would not leave the house. She would need alcohol to leave the house and this was only to get more alcohol. She admitted through in her assessment that she was using alcohol to self-medicate for her anxiety and depression. This seems to be a common theme we see in the outpatient clinic for this cohort of patients.

The role of the non-medical prescriber and the clinic was to keep the patient off alcohol. Carol was developing some symptoms of a decompensated liver and scarring was found on her liver at her last ultrasound. She did know the importance of staying off alcohol. However, her alcohol-free days had been difficult to manage as she was very anxious, craving and could not sleep. Common problems associated with being alcohol free should not be long term, unless the patient is suffering from anxiety and depression, as Carol was in this case. She had previously been on sertraline but this was not useful she felt. She could not sleep and often used alcohol instead of taking her sertraline to manage her anxiety and depression.

She had never tried acamprosate for alcohol craving and when this medication was explained to her she felt it would be beneficial, and this was prescribed. The prescriber discussed changing her antidepressant medication to a more sedative one (mirtazapine) that could help her sleep. The prescriber liaised with her GP who stopped the sertraline, and she was initially prescribed the mirtazapine. When prescribing a new medication it is important to monitor patients every 2–4 weeks; therefore, Carol was seen every 2 weeks until she settled on the medication.

After 4 weeks Carol described her mood as much better and she was sleeping. The mirtazapine she felt had really worked for her and she was far less anxious during the day. Her cravings, although still apparent, were at a level she could cope with. She was able to stay alcohol free after 4 weeks and this was something she had not been able to do for many years. After 5 months she is still alcohol free; she has had one lapse but was able to return to abstinence quickly. She is more confident about her ability to be alcohol free after that episode and feels she wants to stay that way. She has had no hospital admissions for 5 months and this is new as she would have had at least one in this time period. She feels positive that she can sustain this long term and feels happy she has managed to stay off alcohol.

In terms of treatment, it was important that she saw an experienced non-medical prescriber who was confident in prescribing in the field of alcohol dependency and depression. This enabled the service to prescribe effectively for Carol and ensured a positive outcome for her. The feedback she gave also emphasised this point.

Feedback from Carol

‘The clinic was easy access, and the fact that I could finally get my depression and anxiety managed without alcohol was so important and this was like being in a responsive and patient-orientated service. This was the service I wanted for so long … but have found hard to find. I thought when I came for my first appointment this was going to be another service where I would struggle to stay off alcohol, and my needs for managing my anxiety not met. I was wrong. Both being treated by the same clinician was so effective for me. A god-send I cannot say more than this … Also, I can get all my treatment seeing one person in one appointment. Saved a lot of time and worry, and due to the service being quick and easy to access I would always prefer to come to the outpatient clinics. It is not far for me to travel as well. It is better than local services for alcohol as it is quicker and you get medication quicker.’

Colin

Colin came in with ulcerations and some elevated blood tests related to his liver function. He had been drinking 26 units daily for many months. He was working and described himself as a functioning alcoholic; however, through excessive alcohol consumption he lost his job.

He became depressed and isolated staying at home and only going out to get alcohol, and he had a partner who worried about him. Since losing his job his alcohol intake had increased to 40–50 units some days. He developed stomach pains and started to vomit after alcohol and, often, this was associated with blood present in the vomit. He came to A&E and was admitted with ulcers, which he received treatment for. He was given an alcohol detoxification programme while in hospital and was told to stop alcohol for a while as it would be beneficial for his health. He did want to stop alcohol as the stomach pain he experienced after drinking was difficult to tolerate.

He had been, in the past, to his local alcohol service but felt they could not accommodate him as he was a functioning alcoholic and was working. He wanted a detoxification from alcohol last year, but was refused this by his local alcohol service. He was never clear on why. Due to this experience he did not want to go back there and engaged with the outpatient clinic.

He was seen 3 weeks after he was discharged from hospital alcohol free. He was on proton pump inhibitors (omeprazole) and was alcohol free when he was seen. He described himself as struggling to stay off alcohol and wanted something to help. He had acute cravings. He was also finding sleep difficult, and often was so anxious daily he would struggle to leave the house. He only came to the appointment as he had a friend bring him. He had always been anxious and had never taken antidepressants before. He felt this was a health need that had been difficult for him to get treatment for as his GP would not start him on an antidepressant because he was drinking too much. However, he was now abstinent so this was the best time to start him on a suitable antidepressant.

As the guidance indicates, he was started on mirtazapine and seen every 2 weeks initially. This seemed to work for him quickly, as he started to have a better sleep pattern after a week. He was also prescribed acamprosate for the cravings and this worked well for him as he did seem more relaxed. This could have been due to the mirtazapine being a sedative antidepressant. However, the acamprosate was also working well as he described less intense cravings. The ability of the non-medical prescriber to think holistically and look at depression and anxiety as well as alcohol dependency is important to treat patients effectively, as this case study illustrates. It is important that the prescriber's skill set and knowledge is used for good patient outcomes.

This case shows what an experienced and knowledgeable prescriber can achieve in an area of mental health that has embraced the concept of nurse prescribing. This can be well received by patients and examples like these should be shared and promoted to make non-medical prescribing more uniform across the mental health sector.

Feedback from Colin

‘I felt really well cared for as my anxiety and cravings were dealt with in one appointment. The follow-up was good as it was the same person I saw as well. Giving the nurse a picture of myself that grew overtime. I was very grateful … I was given good information on mirtazapine as I was not keen to start this … however, with good information from the nurse and regular contact I am glad I started this … I am in a better place because of this.’

Discussion

The case studies in this article have highlighted the important contribution an experienced and competent non-medical can make in mental health services. The area of substance misuse and addictions has embraced the concept of non-medical prescribing, and the rest of the mental health sector needs to recognise the difference this can make to patients.

Indeed, if patients prefer this model and feel it meets their needs better than the traditional doctor–patient appointment (Gumber et al, 2011), this should be encouraged and streamlined in the mental health sector. This will lead to more choice and better engagement for patients. Making this change and using nursing resources more widely and in a patient-centred way by expanding the role of the non-medical prescriber in inpatient and outpatient mental health settings would enable more positive patient outcomes.

Key Points

- Non-medical prescribing is not widely used across all sectors of mental healthcare

- This article provides some rationale as to why this is the case. However, it also promotes non-medical prescribing provision and its benefits by examining an area where this is extensively used. It focuses on the area of alcohol dependency and promotes the positive role this can provide for patients

- This is to illustrate to all mental health sectors what can be possible for their services and their patients, with some major benefits which can transform service provision

CPD reflective questions

- What are the benefits of independent non-medical prescribing for:

- - Prescriber and patient relationship

- - Patient access to treatment

- - Effect on DNA rates

- What can mental health services learn from areas where non-medical prescribing provision is established?

- What are the main benefits for patients accessing non-medical prescribing clinical setting?