The author is a respiratory nurse specialist (RNS) practising as part of a community nurse-led respiratory assessment service. The RNS is responsible for ensuring that individuals with respiratory disease receive holistic care and is are empowered to develop expertise and advanced professional practice. The Department of Health (DH) (2008) advocated that such proficiency should be achieved through the appropriation of non-medical prescribing, which is now recognised as one of the most important developments in nursing since it became a profession in the early 20th century (Dowden, 2016).

The benefits of nurse prescribing are well documented, with qualitative evidence demonstrating positive outcomes in efficiency of care (Courtenay et al, 2011), increased nurse autonomy (Watterson et al, 2009) and greater patient satisfaction (Carey and Stenner, 2011). Therefore, with current governmental demands to ensure high-quality care provision regionally (Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety (DHSSPS), 2012) and nationally (DH, 2009), independent and supplementary non-medical prescribing has been recognised as a valuable asset for advanced nursing practice.

Nuttall (2016) has argued that it is important to differentiate between the two forms of non-medical prescribing:

- Supplementary prescribing refers to prescription from a specified clinical management plan implemented by an independent prescriber (DH, 2005)

- Independent prescribing allows for prescribing decisions to be made within individual scope of competency (Lovatt, 2010), with its current definition applicable to the RNS role. Nurses, pharmacists, optometrists, physiotherapists and podiatrists can be independent prescribers and they are (Department of Health (Northern Ireland), 2019):

‘… responsible and accountable for the assessment of patients with undiagnosed and diagnosed conditions and for decisions about the clinical management required, including prescribing.’

The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) demands that nurses prescribe only if they possess sufficient knowledge of the patient's health and that the treatment prescribed will serve the person's health needs (NMC, 2018a). To ensure safe and effective prescribing it is therefore the nurse's responsibility to complete a holistic assessment(Silverston, 2014), including history taking and a clinical examination (Rutt-Howard, 2016). It is of significance, however, that, if during this process an issue regarding patient safety is identified, this should be addressed appropriately, because it can affect both the prescribing process and the eventual prescribing decision.

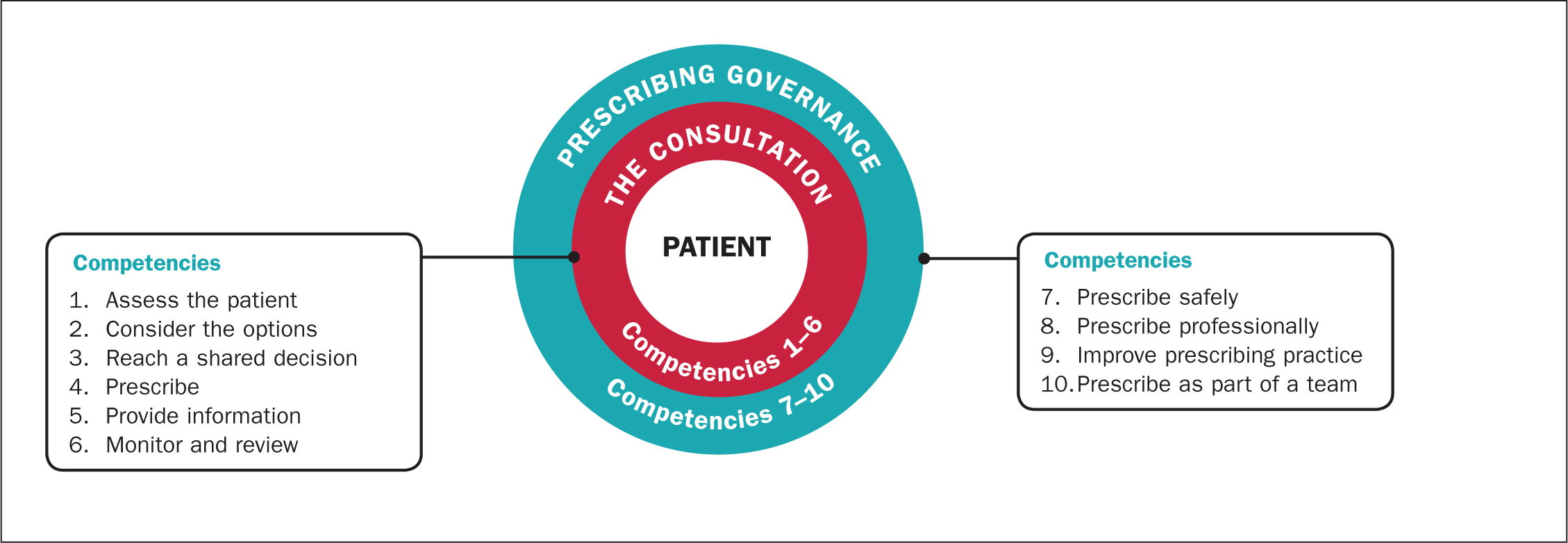

The aim of this article is therefore to critically evaluate an issue that poses a challenge to the RNS as an independent prescriber. The context of a care study is used for analysis: the author used the context of the Prescribing Competency Framework (Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS), 2016) (Figure 1) to explore the professional, legal and ethical issues involved in ensuring safe and appropriate prescribing are explored, along with rigorous appraisal of the evidence base.

Sue White (not her real name) is a 75-year-old patient who was referred by her GP to the home oxygen service assessment and review clinic, which is led by the RNS, for assessment of suitability for long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT). Assessment for LTOT is a core component of the respiratory service, with the RNS ideally placed to assess, examine and treat patients autonomously, while applying expert knowledge and clinical judgement to manage and complete episodes of respiratory care, an approach recommended for advanced nursing independent prescribing practice (DH, 2006; RPS, 2016).

Preparation for consultation through review of medical records and a referral letter provided valuable information about Mrs White's current diagnoses and treatments, assisting in planning areas for exploration (Bickley, 2014). She met the requirements for referral to the home oxygen service assessment and review clinic, in that she had a definite diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and was undergoing optimised medical treatment as recommended by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) (2017). She also had a resting stable oxygen saturation of less than 92%, fulfilling the core recommendation for LTOT eligibility referral (Hardinge et al, 2015).

The RNS acknowledged the progressive nature of COPD whereby destruction of the respiratory airways predisposes to eventual lack of ventilation and impairment of normal gas transfer (Hinkle and Cheever, 2014), leading to persistent blood oxygenation reduction (Kent et al, 2011). This is known as chronic hypoxaemia (Porth, 2015), a common complication in advanced COPD that usually requires consideration for LTOT (GOLD, 2017; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2018).

The competency framework (Figure 1) promotes safe prescribing practice through the assessment of the risk and benefits of taking or not taking a medicine or treatment while critically analysing a reliable and validated evidence base (RPS, 2016). The NMC (2018a) advises that prescribing practice must be evidence-based and in accordance with relevant guidance. This builds on legislation that non-medical prescribers have a professional expectation to ensure adherence to the best evidence and guidance available for safe and effective prescribing (DH, 2009).

A review of the evidence showed best practice guidance on the survival benefit in COPD that is complicated by severe chronic hypoxaemia continues to be informed by two landmark randomised controlled trials (Nocturnal Oxygen Therapy Trial Group (NOTT), 1980; Medical Research Council, 1981). These are used alongside recommendations by Hardinge et al (2015) that provide algorithms for referral, consideration and assessment for LTOT in COPD. Assessment and examination of Mrs White was therefore required to ascertain whether LTOT was indicated, with evaluation of arterial blood gases central to the decision (Suntharalingam et al, 2016). The patient's result confirmed low blood oxygen levels, and she was therefore to be considered for LTOT (DHSSPS, 2015; Hardinge et al, 2015). However, the RNS acknowledged that the referral letter specified that Mrs White was a current smoker, raising safety concerns in relation to the potential prescribing decision.

Although it is therapeutic, oxygen therapy is also a potential fire hazard. Cooper (2015) highlighted how oxygen, when exposed to a naked flame can become a serious hazard, with the potential for injury and death. A retrospective review of 1199 adult burn patients identified that the risk of fire and burn injury related to cigarette smoking and LTOT is of growing concern (Murabit and Tredget, 2012), with quantitative retrospective reviews demonstrating fatality or devastating head and neck burns due to ignition close to the patient's face (Chang et al, 2001; Robb et al, 2003; Amani et al, 2012). Hassan et al (2010) highlighted that such subsequent inhalation injuries usually require advanced airway management.

Arguably, home oxygen-related burns are prevalent among the COPD population. In the context of a case study, Lindford et al (2006) conducted a literature review on reported cases of burns in home oxygen users in the UK and identified COPD as the most common diagnosis; about two-thirds of patients were current smokers and the mortality rate was 10%. In another study (Murabit and Tredget, 2012), retrospective epidemiological data on COPD patients treated between 1999 and 2008 found similar evidence, with an 11.8% mortality rate during hospitalisation as a result of smoking-related burn injury in patients on home oxygen therapy.

A previous survey of domiciliary oxygen users selected from lists of healthcare providers and visited in their own homes demonstrated a prevalence of smoking of between 14% and 51% (Shiner et al, 1997). Participation data from a randomised controlled trial by Lacasse et al (2005) analysing oxygen therapy in COPD found that up to one-fifth of individuals continued to smoke. The risk of fire hazard can therefore be considered a significant safety consideration, with more research required to adequately quantify the assumed growing prevalence within this specific patient population.

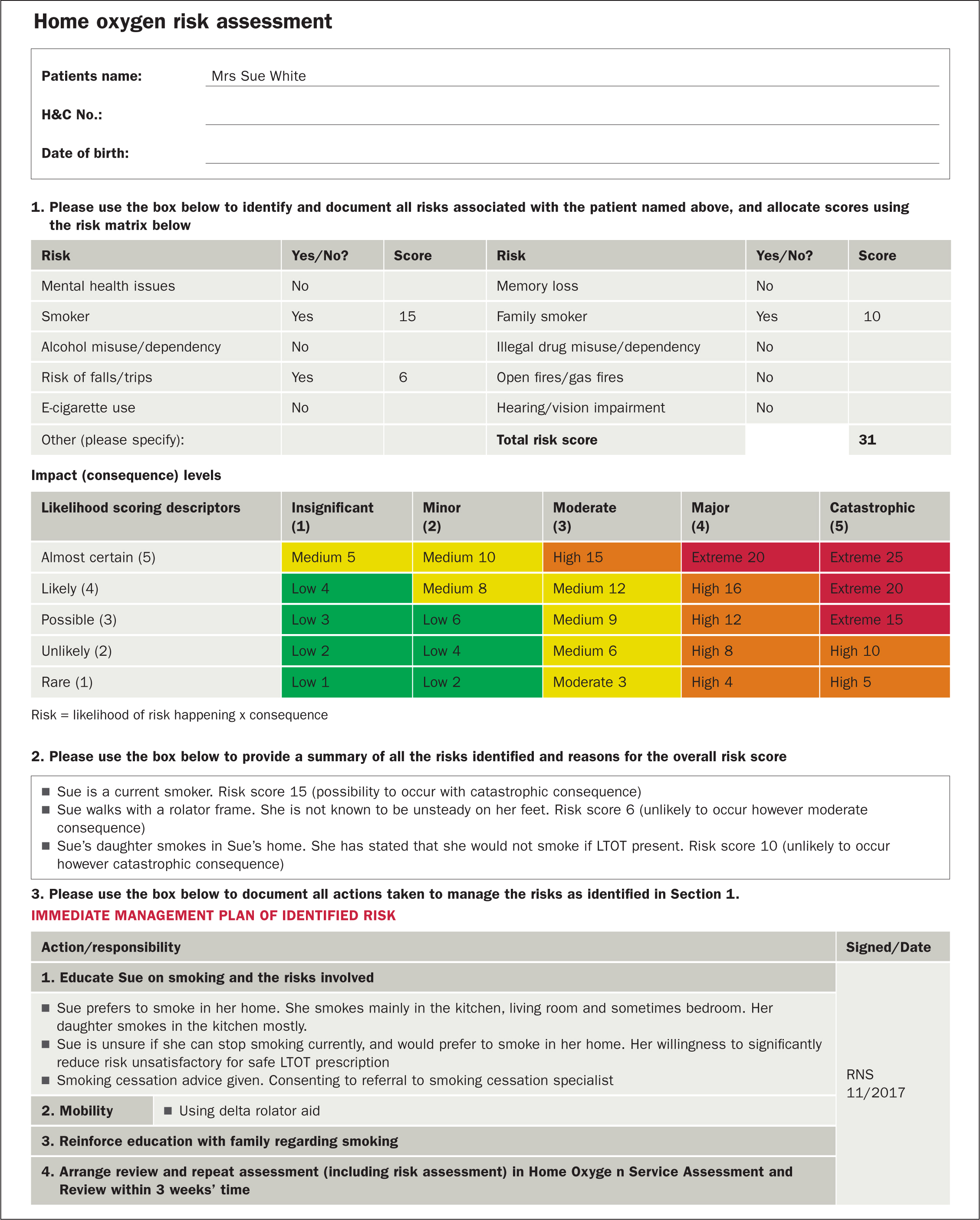

It is therefore essential for the RNS, as an independent prescriber, to recognise potential hazards of LTOT and assess all relative risks with current smokers (Suntharalingam et al, 2016). Minimising harm through risk assessment is fundamental for safe prescribing practice (Broadhead, 2016). The author determined that Mrs White was at high risk of unsafe LTOT by completing a recognised structured oxygen risk assessment tool (Hardinge et al, 2015) (Figure 2), leaving the author with the dilemma of whether to prescribe LTOT to improve the patient's quantity of life, or not to prescribe it due to the significant risk of personal injury.

Cooper (2010) argued that dilemmas are frequent in prescribing practice, and a combined application of personal, group and philosophical ethics are needed for successful decision-making. The author therefore adopted virtue ethics, whereby embracing the virtues of honesty, care, benevolence and courage can help enable safe and effective prescribing decisions (Edwards, 2009). Influenced by the approach of principalism (Beauchamp and Childress, 2013), the author worked to reach a shared decision with Mrs White regarding LTOT prescription.

For successful shared decision-making the nurse prescriber must respect and protect the patient's autonomy (Adams, 2010). Griffith and Tengnah (2014) and Lovatt (2010), however, argued that, although patient choice must be considered a fundamental right, it cannot be honoured if the autonomous decision is unacceptable. Broadhead (2016) suggested that in prescribing practice it can be difficult to achieve this balance. In such instances, prescribers tend to adopt a protective approach through a desire to act in the patient's best interests and, although it could be argued that this is paternalistic (Edwards and Elwyn, 2009), it can be overcome by developing a therapeutic and trusting patient-prescriber partnership.

The Standards of Proficiency for Registered Nurses (NMC, 2018b) state that nurses must ‘support and enable people at all stages of life and in all care settings to make informed choices about how to manage health challenges’, a principle the RNS adopted in building foundations of partnership with Mrs White. This was facilitated through disclosure of appropriate information relating to LTOT risk and benefit, including potential for non-prescription. Mrs White clearly recognised the benefits of the therapy, but expressed her own dilemma: although she was happy to be prescribed LTOT, she was also apprehensive, due to the risks involved and her uncertainty about being able to stop smoking. The RNS therefore sought to further develop the patient–prescriber relationship, whereby Mrs White could relinquish some autonomy in favour of the RNS's clinical judgement, a strategy commonly favoured to resolve difficult prescribing consultations (Broadhead, 2016).

To further develop the patient–prescriber partnership, Mrs White required reassurance that the RNS was applying principles of justice, ensuring that she would receive equal and fair treatment (Adams, 2010). The RNS provided clarity that Mrs White was being treated fairly and that the prescribing decision would not be underpinned by discrimination due to her smoking status. Cooper (2015) acknowledged the ethical argument of discrimination through withholding treatment, recognising however that health professionals have a duty of care to protect patients from harm. Edwards (2009) therefore argued that this sensitive issue must be discussed thoroughly in order to demonstrate consideration for patient autonomy and respect for the patient as a person.

Griffith and Tengnah (2014) argued that patients' wellbeing should be promoted and exercised through acting in a beneficent and non-maleficent manner. The RNS considered application of this concept in two ways, whereby the author could optimise good through prescribing LTOT, but also maintain the patient's wellbeing by preventing harm through non-prescription. The RNS therefore acknowledged that to achieve beneficence required acting with compassion that is not only within the law, but also in the patient's best interests (Broadhead, 2016).

Writing about the complexity of advanced clinical decision-making in prescribing, Young (2010) suggested that accountability can motivate and influence decision-making for the nurse prescriber, giving responsibility for prescribing error and mistake. The NMC (2018b) states:

‘Registered nurses play a vital role in providing, leading and coordinating care that is compassionate, evidence-based, and person-centred. They are accountable for their own actions and must be able to work autonomously, or as an equal partner with a range of other professionals, and in interdisciplinary teams.’

The legal considerations regarding this are within tort law, which centres on liability due to acts or breaches in the duty of care leading to harm or injury of another person: there is therefore direct accountability for causing harm as a result of prescribing (Broadhead, 2016). It is therefore essential to recognise the duty of care that nurses have to patients, and the RNS considered whether it was possible to foresee the likelihood of injury to Mrs White as a result of a prescribing decision (Herring, 2008). Furthermore, in the context of professional indemnity and vicarious liability, the RNS had to consider the potential consequences of inadvertently incurring harm to the patient (Dimond, 2011), which could have resulted in Mrs White claiming that a mistake in clinical judgement had led to the unsafe prescription of therapy.

With harm considered from the perspectives of both the patient and the RNS, the author suggested strategies to overcome and minimise risk, a method frequently used to promote non-maleficent prescribing practice (Broadhead, 2016). This involved referring Mrs White to a smoking cessation service, an action advised for all smokers regardless of a need for LTOT; this alone can improve survival outcome for patients with COPD (Suntharalingam et al, 2016). It is also in line with regional and national guidance that recommends offering smoking cessation counselling by trained advisors to all LTOT candidates (DHSSPS, 2015; Hardinge et al, 2015).

The RNS also considered strategies to reduce the risks with Mrs White should LTOT be prescribed while she continued to smoke. Smoking cessation is clearly recognised as an effective action to reducing the risk of fire with home oxygen therapy, but there are other possible approaches to explore. For example, national guidelines produced for the British Thoracic Society (BTS) (Hardinge et al, 2015) highlight the contractual responsibilities of home oxygen providers to conduct a home risk assessment prior to LTOT installation, which should include notifying the prescriber if any fire-related risks are identified. In addition, the use of safety devices such as fire breaks and flow-stop devices on all LTOT equipment is currently a legal requirement under European Union regulations for companies manufacturing home oxygen equipment, in order to reduce the acceleration of oxygen-related fires, prevent death and reduce the severity of any subsequent injury (Cooper, 2015). The author recognised that, although such strategies are useful in the context of the prescribing decision and can help reduce risk for Mrs White, they most certainly do not remove the risk completely.

The competency framework recommends that relevant prescribing frameworks, policies and guidelines be used for prescribing decisions (RPS, 2016). With previous national guidance from the BTS (2006) being described as vague in its LTOT prescription recommendations for smokers (Lacasse et al, 2006), its update (Hardinge et al, 2015) has been welcomed: it recommends assessment and consideration on a case-by-case basis focusing on patient attitude towards risk and smoking behaviour. This updated guidance (Hardinge et al, 2015) implies that, where there is reasonable doubt and if, in the prescriber's judgement, the risk is too high, LTOT should not prescribed.

Considering the outcomes from Mrs White's risk assessment, the author had cause for reasonable doubt about the safety of home oxygen therapy. The NMC (2018a) recommends that nurses make timely and appropriate referrals to other practitioners, when this is in the best interests of the patient. With this in mind, the RNS discussed Mrs White's risk assessment with the respiratory nurse consultant, who agreed that it would be unsafe to prescribe LTOT at this time.

Although the benefits of LTOT in COPD are clear, it is the responsibility of the RNS to attempt to eliminate or reduce the risk of burn injury before prescription. By making an individualised and careful risk assessment the author was able to foresee the professional, legal and ethical dilemmas posed; there were grounds to consider the possibility of inadvertent harm to Mrs White despite beneficent intentions. Therefore, in disclosing the rationale for not prescribing LTOT, the RNS was able to maintain honesty and integrity with Mrs White, enabling informed shared decision-making, whereby the patient recognised not only the benefits of LTOT, but also the realisation of its potential unsafe use. Development of this trusting and therapeutic relationship placed Mrs White at the centre of her care, resulting in a shared autonomous decision for referral to smoking cessation. The Prescribing Competency Framework (RPS, 2016) (Figure 1) advocates that a satisfactory outcome be achieved for both the patient and the prescriber, and this was facilitated through the joint decision by the RNS and Mrs White to review her again at the home oxygen service assessment and review clinic at a later date to repeat her oxygen assessment and reconsider safe LTOT prescription.

Home oxygen therapy is a potential serious fire hazard for patients, with unsafe use potentially leading to personal injury or even death. It is the responsibility of the RNS as an independent nurse prescriber to educate patients about the risks of smoking and home oxygen therapy, including completion of an individualised patient-centred risk assessment before making a prescribing decision. There is clear evidence that smoking cessation not only reduces the risk of unsafe LTOT use, but that as an approach on its own it can improve survival outcome in the COPD population (Suntharalingam et al, 2016). It should therefore be a priority for all health professionals.

Independent nurse prescribers who encounter similar dilemmas regarding the safe prescription of home oxygen therapy should consider the approaches described in this article to help them appraise the professional, legal and ethical issues involved the decision whether or not to prescribe LTOT for a particular patient.

Key Points

- Best practice evidence recommends that individuals with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and resting hypoxaemia (PaO2≤7.3kPa) should be assessed for long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT)

- Oxygen therapy is an obvious fire hazard, with several studies demonstrating that cigarette smoking and LTOT use can lead to fatality and personal injury

- Smoking cessation alone can improve survival outcome in COPD

- Implementation of the Prescribing Competency Framework can help Independent nurse prescribers, who are accountable and responsible for their prescribing decision, to consider the professional, ethical and legal issues to make safe prescribing decisions for LTOT in patients with COPD who are current smokers

CPD reflective questions

- Consider prescribing in your clinical setting. What can you do to enhance the safety of prescribing LTOT?

- What issues have you encountered that have posed a challenge to your prescribing practice?

- Reflect on those challenges. What measures did you take to manage such situations from professional, ethical and legal points of view?