As a large provider of multi-professional non-medical prescribing (NMP) education, University of the West of England (UWE) attracts learners from across the southwest of England and beyond. The design and delivery of the NMP programme has been developed with practice partners, including the Royal Devon University Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust (RDUH), service user engagement and learner feedback. The underlying premise has been to ensure that there is consistency in the preparation, educational experience and assessment of all learners, while supporting the current regulatory requirements of the General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC), the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) and the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC).

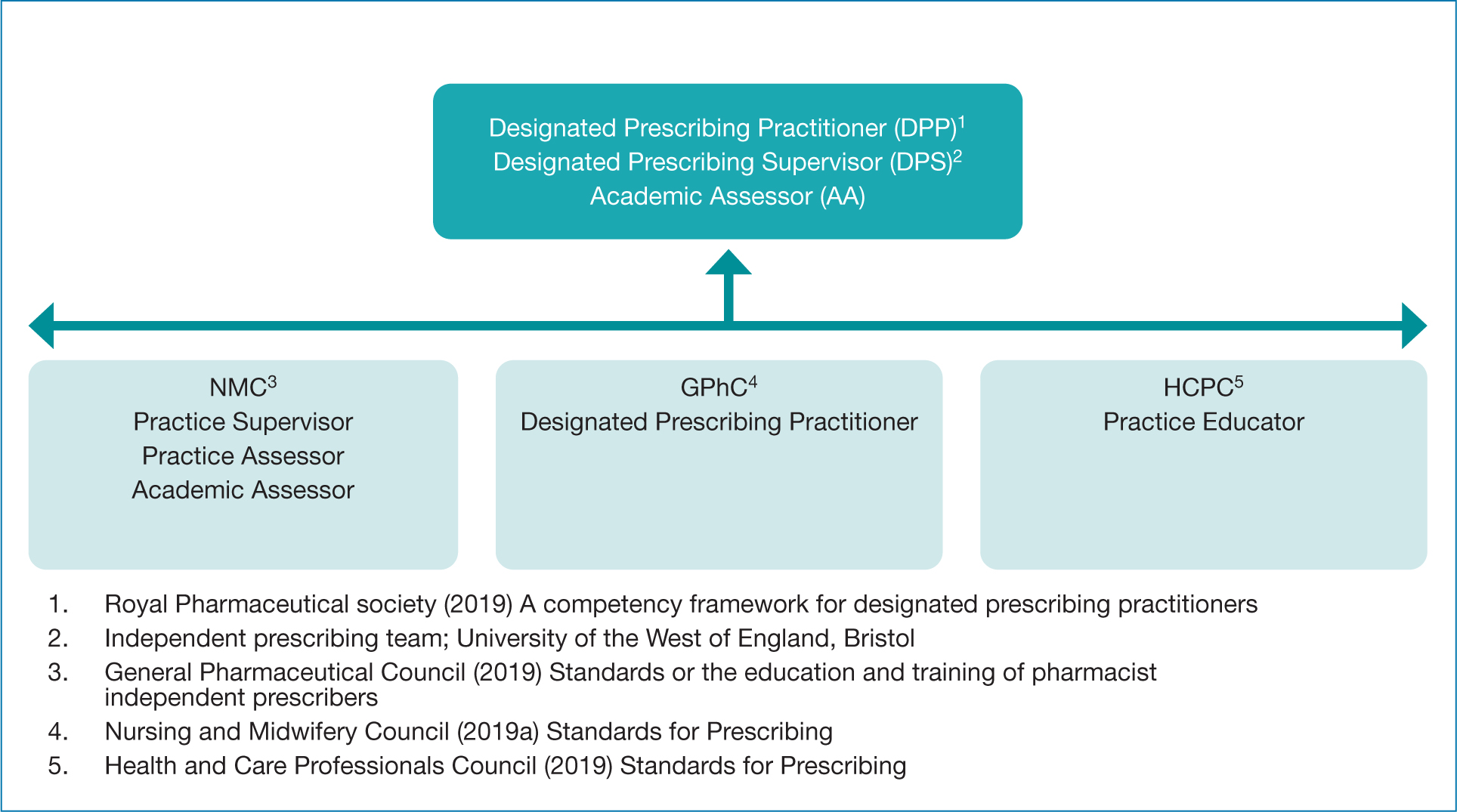

In 2019, professional regulatory changes expanded the professions able to take on the supervision and assessment of NMP student practice placements, increasing the supervisor pool and potentially improving access to NMP training (GPhC, 2019; HCPC, 2019a; NMC, 2019a). Nurse, pharmacist and allied health professional (AHP) NMPs are now able to support practice placements in addition to doctors. At the same time, the NMC (2019b) brought in changes which mandated that nurses undertaking NMP training would need two individuals to support their practice placement; a practice supervisor (responsible for providing supervision and support) and a practice assessor (responsible for the overall assessment of the student). This contrasted with the GPhC and the HCPC who only require that a single person undertake this role. The regulators use different titles for the person undertaking the assessor role; however, in this article, the umbrella term designated prescribing practitioner (DPP) will be used for clarity.

As they were involved with organisations tasked, the authors were keen to develop systems which helped support multi-professional supervision and assessment in practice, thereby helping to grow the future DPP workforce.

Supporting the regulatory changes

The university perspective

UWE is one of the largest providers of multi-professional NMP education in England and trains around 500 NMPs each year. To support a consistent approach to the practice understanding and application of the roles, a common approach to the supervision and assessment of practice learning required by the GPhC, the HCPC and the NMC was adopted (Figure 1). A framework for the supervision and assessment was co-created by the university and stakeholders, mapping regulatory requirements and the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) Competency Framework for DPPs (RPS, 2016). This provided clear guidance on the roles, ensuring that the criteria to undertake them supported a fair and objective assessment to take place and uphold public protection. In addition, it served to underpin internal and external clinical governance requirements for NMP within the university and partner organisations.

Each learner is allocated an academic assessor (AA - university-based) and is required to source a designated prescribing supervisor (DPS) to act as both a practice supervisor and a DPP. This supports the equality of learner experience, increases the future availability of supervisors and assessors and encourages supervision and assessment across professional boundaries. The aim is to support the steady and successful growth of the DPS and DPP roles with the trajectory that learners develop from prescriber, to DPS to DPP. The vision is this becomes the standard path. Doctors can continue to undertake either the DPP or the DPS role.

The NHS Trust perspective

The RDUH trust covers both community and acute sectors, and employs approximately 350 NMPs, with around 50 staff undertaking the NMP course on an annual basis. It has a dedicated NMP lead who supports the ongoing development of NMP. In preparation for the implementation of the new DPS/DPP roles, the NMP lead made a number of changes. These included:

- Regular communication to all NMPs about the regulatory changes, in the year preceding implementation

- Updating the NMP policy to include a definition and description of the new roles

- Updating the application process for NMPs (to include sign off by both the DPP and DPS, and confirmation that the DPP met the requirements of the RPS competency framework)

- Online update session for all DPPs and DPSs (including medics) at the start of the course, focussing on governance in the organisation and where to get support if needed

- Monthly peer supervision sessions for all DPPs and DPSs.

Evaluating the impact of the changes

A survey of over 1000 NMPs in the south of England found that just under half of them (42%) were not interested in becoming DPPs, with lack of time being the main reason cited (Jarmain, 2020). Those who wanted to undertake this role said that they would need designated time, a supportive organisational policy/DPP competencies, training and peer support. Since this survey was undertaken, the RPS Competency Framework for DPPs has been published (RPS, 2019), providing clear guidance on the expected competencies. Another survey of nearly 100 pharmacist NMPs and pharmacy leads in Scotland found that there was positivity and acceptance of the DPP role, with suggested drivers including improved patient care, enhanced reputation of the pharmacy profession and the skills of individual pharmacists, and payment/other incentives (Jebara et al, 2022). While both of these surveys give us an understanding of the views of NMPs pre-implementation, there have not been any studies published on the experiences of NMPs who have undertaken these roles.

There is some urgency to understand how the DPP/DPS role is working in practice. As well as the need to increase the NMP workforce generally to meet the demand on the NHS, the GPhC have announced that all pharmacists will graduate with an independent prescribing qualification from 2026 (GPhC, 2019). This will put significant pressure on the system to find enough NMPs willing and able to undertake the role of DPP over the coming years (Burns, 2022). To understand how the role was working, it was decided that we would conduct a programme/service evaluation across UWE and RDUH. The authors agreed that the evaluation would focus on those undertaking the role of DPS, so that we could focus fully on their experience and how this may impact on their willingness to undertake the DPP role in the future.

Methods

Aim

To understand the experience of NMPs undertaking the role of DPS for the first time with students on the NMP course.

Design

The DPS role was evaluated using a mixed methods approach, which was co-designed by the UWE independent prescribing team and the RDUH NMP lead through engagement with key stakeholders. Stakeholders, defined by those directly affected by an intervention (The Health Foundation, 2015), included DPSs, NMP Leads and commissioners.

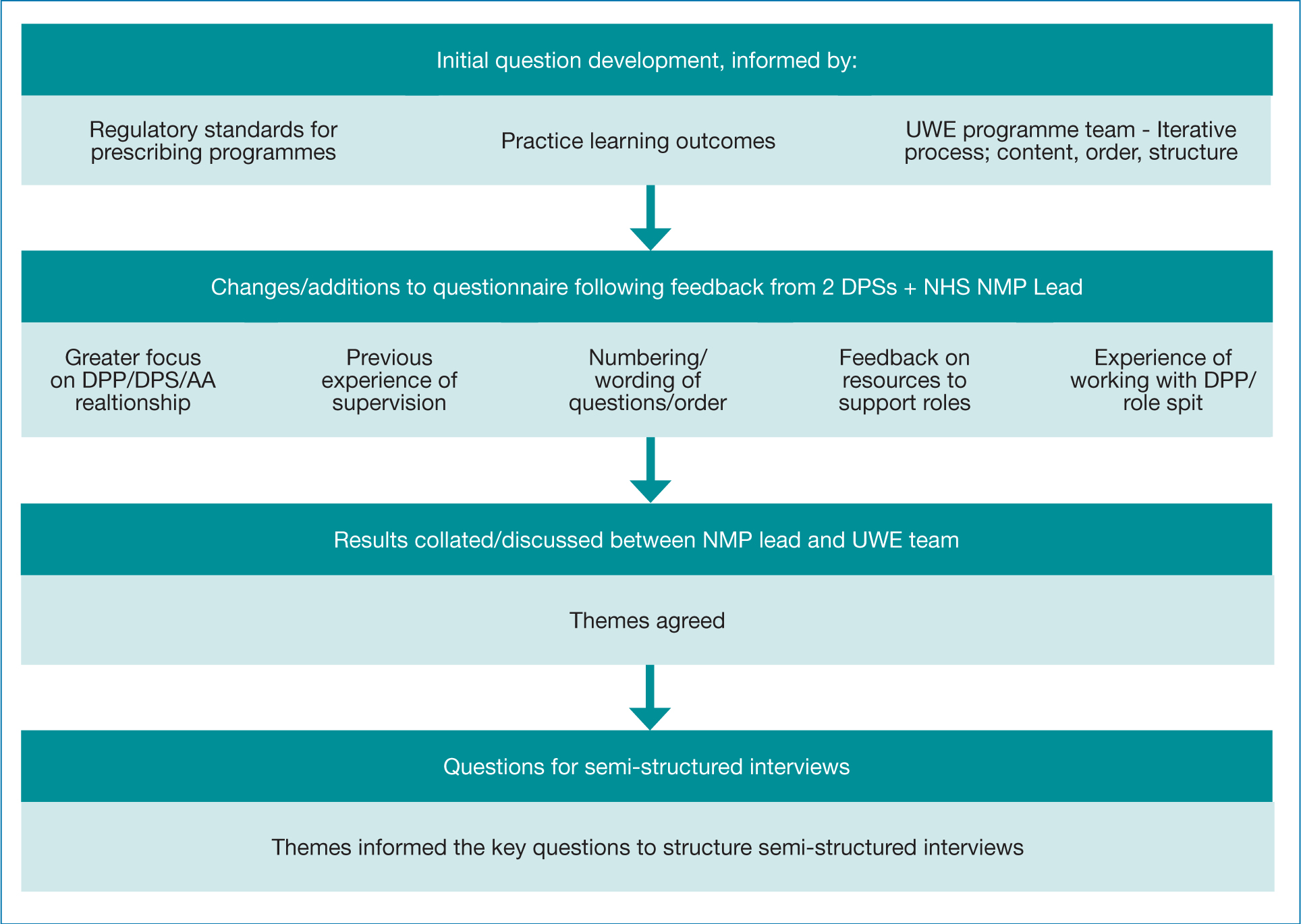

A collaborative approach between the UWE team and the RDUH. NMP lead was adopted throughout the evaluation process through regular meetings, discussions and iterative development of evaluation methods. The evaluation comprised of an electronic questionnaire evaluating the individual's experience as a DPS, the themes from which informed the focus of the semi-structured interviews. This was intended to reflect a cyclical process whereby programme evaluation informs service development (Figure 2).

It was decided that a completely randomised sampling approach for the semi-structured interviews would not be appropriate, as there were several universities where RDUH staff were currently undertaking the NMP course and differences in training/support between universities could provide confounding variables. Participants were therefore limited to UWE DPSs. There were 18 DPSs in the Trust who met this criterion, and they were all invited to attend a semi-structured interview; ten of them agreed to do so.

As a programme/service evaluation, this study did not require review through the research ethics committee (Department of Health, 2021), however, it was discussed and ratified by the research and development lead of the Trust and the UWE Faculty Chair of the Ethics Committee. Consent was explored fully with potential questionnaire participants through assurance of the purpose of the evaluation, anonymity and allowing DPSs to access the questionnaire and only completing it if they wished. All interview participants were provided with a participant information sheet about the study. They were aware that all data collected would be anonymised and that they were under no obligation to take part.

Data collection

An electronic questionnaire was distributed electronically using Microsoft Forms during December 2021 to the 100 DPSs registered with a UWE NMP student from the September 2021 intake of students. Of the DPSs, 34 responded, with a response rate of 34%. This is in line with response rates reported by other online surveys in education which vary from 20%–47% (Nulty, 2008). Open and closed questions were included to enable quantitative and qualitative data. Twenty-two questions were included in the survey with a completion time estimated to be seven minutes.

Interview participants attended a semi-structured interview. These were conducted on Microsoft Teams by one of the authors (the NMP lead for the Trust) and recorded. The interviews lasted between 30 and 75 minutes and were transcribed following the meeting. All data which could identify the participants were removed (this included names and any comments relating specifically to the name of their workplace) before the transcripts were shared with the two university lecturers.

Data analysis

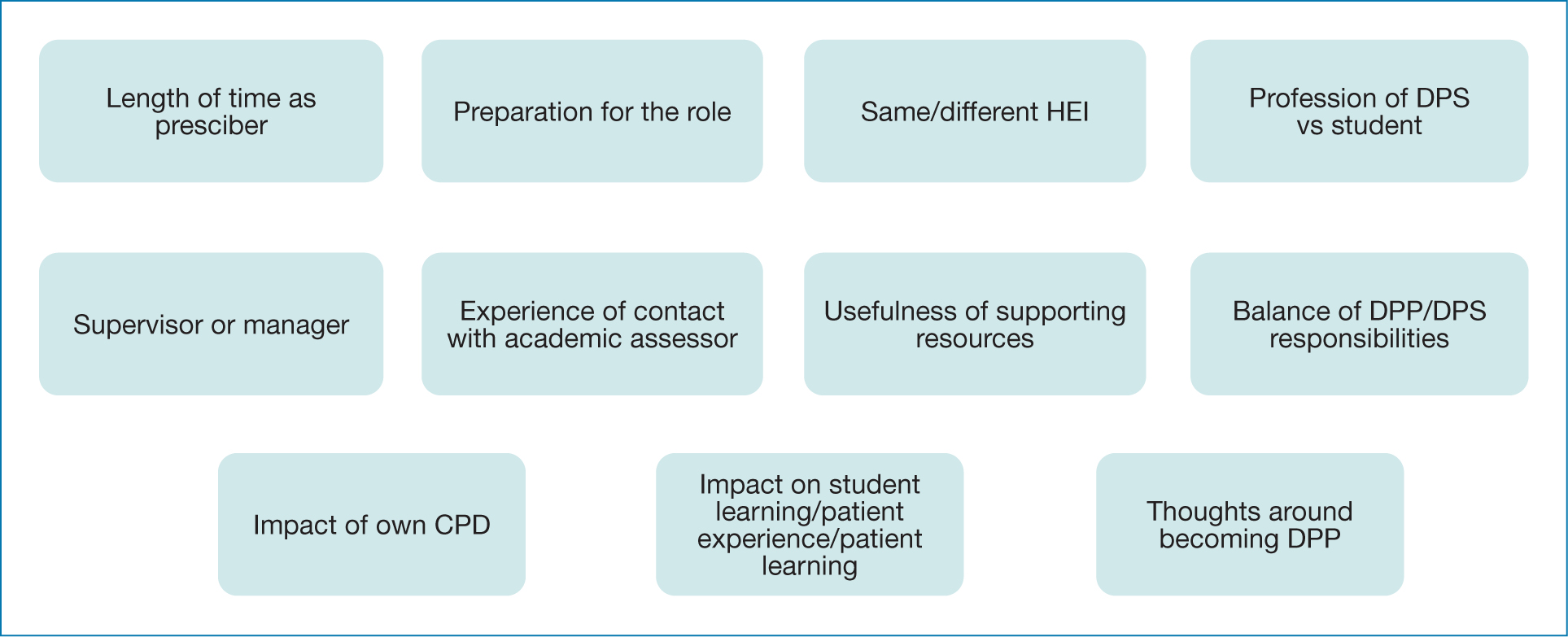

The results of the questionnaire were shared with DPSs anonymously. Following a review of the responses from the survey, an iterative approach within the evaluation team supported the compilation of questions for the semi-structured interviews. Open-ended questions were used to explore themes that emerged from the questionnaire in more depth (Figure 3).

A thematic analysis was then used to identify patterns in the data from the semi-structured interviews, as described by Braun and Clarke (2006). Each transcript was read on repeated occasions and several key themes were identified by each of the authors separately from each other. These themes were cross-referenced for additional rigour. The key themes are summarised below.

Results

There were four main themes identified from the semi-structured interviews. These were cross-referenced against the qualitative responses from the initial investigative survey and were seen to align well.

These were:

- Knowledge and experience prior to undertaking the DPS role

- How the role of DPS was enacted in practice

- Interactions and engagements necessary to support the DPS and underpin students` professional development

- The way in which the DPS role supports personal growth.

Knowledge and experience prior to undertaking the DPS role

Several of the DPSs described how time since qualification as a prescriber gave them the opportunity to build their confidence, ready to undertake the role of DPS. For example:

‘I think it's probably good to have an experienced DPS. I don't think that somebody that had done their prescribing course maybe two years ago is all that established in their prescribing role…it's good to have done it a long time ago, because there's that confidence element.’

DPS 10

Alongside this, the experience of having undertaken the course themselves meant that they felt that they were in a better position to help support their student. For example:

‘I know how much work goes into [the course]. Therefore, I'm much more able to support appropriately.’

DPS 2

Often the support that DPSs provided went far beyond practice learning, extending to elements of academic coaching, advice on the course structure and pastoral care. Moreover, many of them described sharing information on their knowledge of the course content with their students, including past assignments and exam information. One of them described the conversation they had with their student as follows:

‘Can I support you [the student] in any other way? It's not just with your prescribing, but with your exams, with your essays.’

DPS 5

There was a general consensus that the course was extremely challenging and that anything that could be done to support the student would be a good thing, as summed up in the following statement:

‘If you are supporting your students academically, I think that's a little bit of pastoral care, a little bit of compassion for the stresses we put people under whilst they're trying to do a full time job.’

DPS 10

How the role of DPS was enacted in practice

Although the regulatory changes were introduced three years ago, it was the first time that any of the DPSs interviewed had undertaken the role. It was also the first time that the HEI and the Trust had used DPSs to support students undertaking the NMP course. Both organisations had provided training on the nature of the role; however, there was still a lot of misunderstanding on the part of DPSs about what this entailed. In particular, there was confusion about the difference between the DPP and the DPS roles, as illustrated in the following example:

‘I have a rubbish understanding of the two roles, to be honest with you, because as much as the consultant is the [DPP] who is going to sign the paperwork at the end, I'm still also countersigning. But I'm probably working with my student more than they are.’

DPS 2

However, the confusion was not universal. Some were able to clearly articulate their role as a DPS and differentiate it from that of the DPP. Several spoke of their role as being focussed on support, advice and guidance, whereas the DPP role was more about overseeing the practice experience and signing off the student at the end of their placement. As one DPS put it:

‘I suppose I'm kind of the support mechanism for my student and we discuss what would be useful for her to gain certain experiences. So when she talked to me about going off to see various people, I said “what about going and doing this as well?” ….I think her practice assessor has been very much the sign-er off-er of the stuff that she's done.’

DPS 5

There was significant variation in the perceived distribution of work between the two roles. Whilst some variation is of course to be expected given the differing relationships and support needs of the three individuals, some DPSs felt that their role was fairly minimal compared to that of the DPP, whereas others felt that the bulk of the work fell to the DPS, for example:

I'm doing it all, really. Which don't get me wrong, it's alright, but you know [the DPP] needs to have input.’

DPS 1

The majority of the DPSs talked with some pride about how they, as NMPs, were able to facilitate the student's application of prescribing principles to the scope and area of their practice, as in the following examples:

‘It's about knowing what the standards are for NMPs and making sure that the student understands their standards and what's expected and where we draw the line of what we do and what we don't do.’

DPS 2

‘I'm supervising somebody within my own team, so she does a very similar job to me. So actually I think the benefits have been I understand exactly what medicines my student is going to be prescribing… I see what kind of things we both see in our everyday practice so I know what she's likely to come up against. I know the complications she's likely to see.’

DPS 4

Many DPSs felt that as NMPs they were in a better position to be able to understand some of the nuances of being a NMP than their medical counterparts and that this was of benefit to the students that they worked with. Several spoke of how becoming a NMP was a role extension, requiring a specific training course, and this meant that they were likely to feel the weight of prescribing responsibly more than doctors. As one DPS stated:

‘You remember how worried you felt the first time about actually writing the prescription, of the degree of responsibility and the legalities of it, you just know that as a nurse more than a doctor.’

DPS 6

There was a high degree of consistency in the practical application of the role of DPS, with the majority of those interviewed mentioning a fairly informal approach to the supervision they provided. Although they scheduled meetings with their student, they talked about how the bulk of the supervision took place at unscheduled times such as during clinics, in the office after seeing patients or during team meetings. They felt that it was important for them to be accessible, as illustrated by the following:

‘My student has got more because she can just ring me or we can just say, “what do you think about that?” And it just happens. These conversations, they're not always scheduled. I mean, they're ad hoc as well as the formal meetings.’

DPS 6

This informal approach to supervision meant that often their initial concerns about how much time the role would require were not realised, with many commenting that they had absorbed the role into their regular workload and that it had not felt onerous.

Interactions and engagement necessary to support the DPS and underpin students' professional development

Many of those interviewed expressed a degree of initial anxiety about their ability to take on the role of DPS. They wondered whether they had the skills necessary to undertake the role, whether they were carrying out the role correctly and whether they were doing enough for the student. As one DPS said:

‘Have I done it good enough? Have I done it well enough? You're always just thinking, am I being assessed as well?’

DPS 3

Hearing from other DPSs in a similar situation helped provide reassurance, as in the following:

‘The peer supervision sessions are really useful. Absolutely. Especially as I've kind of felt a little bit like, “am I doing this right?”… I remember hearing [another DPS] particularly saying similar things to what I was feeling which was very reassuring.’

DPS 4

Several of those interviewed spoke of how they felt supported by the NMP lead, who they could contact if they had any questions about the role of DPS or concerns about their student. They also talked about the support that they had received from the university, for example:

‘The tutor was quite happy to have a video call and we just chatted through things. Put my mind at ease and that helped, and that was enough.’

DPS 5

It is interesting to note that although both the university and the Trust provided training on the DPS role, it appeared that the individual support (either through the NMP lead or the tutors) was felt to be more useful. DPSs valued having a relationship with someone they could contact if there was a problem, even if they did not need to make use of this.

Another relationship which was of importance was between the DPP and the DPS. When it worked well, the DPSs felt supported and able to approach the DPP if there were any problems. However, this was not always the case, as in the following example:

‘[The DPP has] a difficult personality. I don't like to say it, but it's really true. The student has known him longer than I have, so they have a slightly better relationship, but I just, I'm not sure he thinks that my role is that important.’

DPS 1

The significance of positive professional relationships extended to interactions between the DPS and the student. Many DPSs mentioned the value of having open, honest, supportive and non-judgemental communication with their students to facilitate the practice experience, for example:

‘I think if you've got a bad relationship [with your DPS] and they're overseeing you, how do you get to say to them “I'm struggling” or “I don't understand an aspect” or “I'm worried about my OSCE or my exam?”’

DPS 2

The majority of DPSs were supervising students of the same profession as themselves, but despite this many of them were enthusiastic at the prospect of undertaking the role with other professions in the future, provided they worked in the same speciality. Although some expressed anxieties about their own lack of knowledge (particularly nurse DPSs considering supervising pharmacists) they identified that the opportunities for interprofessional learning would outweigh these concerns. As one DPS put it:

‘[Pharmacists] come at it from a slightly different perspective to us. They have different background knowledge and they pick up things about pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics much more quickly perhaps than we do, but we pick up on the kind of everyday questions that patients have… the kind of practical elements perhaps. So I think it would actually be really interesting. I think I'd like to supervise a pharmacist because I think they would teach me something as well.’

DPS 4

This aspiration for interprofessional learning extended to a general consensus that it was useful to have continued medical input into the practice supervision of NMP students. There were two main reasons cited for this; the training and experience of doctors were different, and as such, there was much to be learnt from them. More importantly, many of the DPSs felt that it was useful to have medical involvement (either as a DPP or a DPS) for the doctor to develop trust in the student who would probably be prescribing alongside them once qualified. For example:

‘Particularly if the person is new to the team, it's good for the consultants to develop that trust…when that person is going to go out and prescribe and the consultant knows them and feels confident that they're making the right decisions.’

DPS 2

How the DPS role supports personal growth

All of the DPSs spoke of the personal benefits derived from undertaking the role. Some of these centred around continuing professional development; they discussed how the role encouraged them to revise aspects of pharmacology and to revisit the RPS competency framework for prescribers, as in the following:

‘I guess some of our clinical discussions are always interesting ‘cause they make you think don't they? You think “oh, what do I do?” And actually what is best practice? Or the student is talking about drugs you are like “Oh, I just need to remind myself, let's go and have a look together at the EMC.’

DPS 3

More than that, however, the role also led to greater job satisfaction. Many of them talked of how good it felt to facilitate the learning of others, helping to grow the future workforce and in doing so affirming that they were competent prescribers. As one DPS said:

‘[Being a DPS] was rewarding and interesting. Knowing that I'm competent in my role made a big difference for me. It will be included in my revalidation.’

DPS 1

The majority of those interviewed said that they would be willing and interested in undertaking the role of DPP in the future, for example:

‘Yeah, be really happy to do [the DPP role]. Like I say, I think the main thing is knowing about the practical paperwork. This is how many times you're expected to meet with your student. This is how much time commitment; I think really specific type things because I don't need lots of discussions about drugs and mentoring and things like that.’

DPP 3

For those who said that they would not want to undertake the DPP role, the reasons cited were a preference for the more supportive nature of the DPS role over the DPP role, and a belief that the individual concerned had been qualified as a NMP for too long for their experience to be relevant to the DPP role.

Discussion

Some have argued that NMPs do not have the skills, training and breadth of knowledge necessary to undertake the new DPP role (HCPC, 2019b). However, the RPS Competency Framework for DPPs (RPS, 2016) assures this by stating that DPPs must be experienced prescribers with up-to-date patient-facing clinical and diagnostic skills. This was very much the case for DPSs in this evaluation who spoke of how their breadth of experience and time since their qualification as a NMP had given them the skills and confidence necessary to undertake their new role. It is interesting to note that long before the recent regulatory changes, students were reporting that their experience would be enhanced by having a NMP as a ‘co-mentor’ alongside their designated medical practitioner (DMP) (Ahuja, 2009) and in the author's evaluation those undertaking the DPS role often felt that it was just formalising an aspect of their job which they had been undertaking on an informal basis for many years; providing coaching, advice and pastoral support. DMPs have previously reported that balancing the support and assessment requirements of their role was problematic (Grimwood and Snell, 2019), and it seems likely that the informal coaching provided by experienced NMPs in the past was in response to this. Health professionals often provide ad hoc training and supervision to students whom they are not officially mentoring (at the pre-registration level, as well as for NMP students qualified to do so) and this is part of what led to NMC regulatory changes which effectively split the role of mentor into that of practice assessor and practice supervisor for nurses (NMC, 2019b).

When questioned about the differences between the DPP and the DPS roles, participants in this evaluation were often unclear about what aspects of the roles fell to which person. This is perhaps unsurprising given that these are new roles and that, even before the recent changes, there was often uncertainty on the part of DMPs about what their role entailed (Courtenay et al, 2011; Grimwood and Snell, 2019). However, the practical application of the role was fairly consistent, with DPSs offering support and mentorship, providing students with easy access to someone with whom they could test out their learning prior to the more formal assessment by the DPP. Previous research has suggested that DMPs may not always have had a good understanding of the competencies required by NMPs (McCormick and Downer, 2012), and many of the DPSs described how they used their knowledge of the RPS Competency Framework for Prescribers (2021) as a structure for development and reflection on learning with their student. Meetings between the DPS and the student were often unscheduled and informal, therefore despite fears expressed by some prior to undertaking the role (Jarmain, 2020), participants in this evaluation were unanimous in reporting that the time commitment was not unduly arduous.

Similar to many people undertaking a new role, several of the DPSs reported experiencing ‘imposter syndrome’; a feeling that perhaps they were not as competent as others believed them to be. Researchers have proposed a variety of strategies for overcoming imposter syndrome, including listening to feedback from others (Nedegaard, 2016), individual reflection (Rivera et al 2021) and peer support (Ruple, 2021). DPSs described using all of these strategies to a varying extent and felt that these, together with ensuring they had a good understanding of the course content, helped them to overcome the self-doubt which they may have experienced initially.

Lack of knowledge about the NMP course has long been highlighted as an issue for DMPs (George et al, 2006) and there was a consensus by evaluation participants that undertaking NMP training themselves had placed them in a better position to support others through the trials and tribulations of an extremely demanding course. However, there may also be problems with this; evaluation participants spoke of sharing their experience of understanding the essays they had written, some of which may no longer have been relevant. Of even more significance is the risk of plagiarism, rates of which have increased over recent years (Suter and Suter, 2018). Where students are reading essays on similar topics to the ones they are required to write, they may be at risk of unintentionally failing to ensure that the work produced by them is entirely original.

Several studies have indicated that DMPs have not felt fully supported by universities in the past (George et al, 2006; McCormick and Downer, 2012; Grimwood and Snell, 2019) and to ensure this was not the case for the new DPPs/DPSs, UWE put in place a structured online training module. This was backed up by a single online training session provided by the NMP lead at the RDUH, and the offer of support/further contact with both organisations. It is noteworthy that many of the DPSs did not feel that the formal training was particularly useful, instead, they valued knowing that someone was there in case they needed to ask for support. It appeared that the primary benefit of providing the training was not the training itself, but more the opportunity to build relationships and develop links between the university, the employer and the DPS.

The majority of the DPSs had pre-existing relationships with their student, often working in the same team/department. However, in common with previous work focussed on DMPs (Avery et al, 2004; Afseth and Paterson, 2017), the experience of providing supervision and regular support appeared to strengthen their relationships significantly. All of those interviewed said that they would be willing to undertake the role of DPS again in the future, and many of them indicated that they would be happy to move into a DPP role. The benefits of undertaking the role were significant and included continuing professional development (both by completing the UWE online training module and updating themselves on pharmacology/prescribing in order to teach their student), enhanced job satisfaction and a greater sense of self-worth.

DPSs were enthusiastic about undertaking the role with students of a different profession to themselves; what mattered to them was that the scope of practice was the same (in line with the RPS Competency Framework for DPPs) rather than the profession. This finding is of considerable importance as we look to expand the number of NMPs from professions other than nursing. In particular, there have been concerns that there are not enough DPPs to meet the demand by pharmacists who will shortly be undertaking NMP training as part of their pre-registration programme (Burns, 2022); interprofessional supervisory relationships which make use of the significant numbers of experienced nurse NMPs and are not purely reliant on doctors are likely to be the solution to this.

Conclusions

DPSs in this evaluation described their role as consisting of coaching, advice and pastoral support, much of which they had been undertaking informally with NMP students for many years before formally taking on the role of DPS. The supervision they provided tended to be unscheduled and informal, often taking place between meetings/clinics. In addition to supporting the practice placement, many DPSs supported students with their academic work, giving feedback on essays and sharing the assignments which they had themselves completed. Although DPSs were offered formal training both by the university and the trust, the primary benefit of this training was that they felt supported and knew where to go in the event of a problem, rather than any benefit derived from the content of the training itself. Undertaking the role of DPS was described as beneficial to their CPD, it enhanced job satisfaction and provided a greater sense of self-worth. Many were enthusiastic about undertaking either the DPS role or offering to support as a DPP in the future, both with students from their own profession and from other professions working in the same speciality as themselves.

Key Points

- DPSs report that their role consists of coaching, advice and pastoral support

- The supervision which DPSs provide to students tends to be unscheduled and informal

- The relationship between the university, the employer and the DPS, and the support which this provided to the DPS, was seen to be more useful than the formal DPS training which was offered

- DPSs feel that undertaking their role is beneficial to their CPD, it enhances job satisfaction and provides a greater sense of self-worth

- Most DPSs in this evaluation would be happy to undertake the role again or offer to support as a DPP in the future, both with students from their own profession and from other professions working in the same specialty as themselves

CPD reflective questions

- What support might you need, if you were considering undertaking the role of practice supervisor or DPP for the first time?

- What was your experience of having a DMP/DPP? How can your learning from this influence how you might undertake the role yourself?

- What might you need to take into consideration if you were to supervise someone from a profession other than yours?