Polypharmacy is one of the three categories mandated by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2017) third global patient safety challenge for action. Through the Medication Without Harm challenge, the WHO aims to ‘reduce severe avoidable medicine related harm globally by 50% in the next 5 years'. Donaldson et al (2017) highlighted the commitment of all health services to the challenge. This will be achieved by encouraging countries and key stakeholders to focus on early action priorities, as well as developmental programmes to improve practice and health systems. In the UK, a short life working group on reducing medication harm was established and reported in February 2018 (Department of Health and Social Care, 2018). Deprescribing is a part of the programme to address excessive polypharmacy and unnecessary prescribing.

What is deprescribing?

There are a number of definitions of the term deprescribing. At its core are facets of the medicines optimisation movement and concerns about polypharmacy, particularly in older adult care.

Deprescribing.org (2020) defines deprescribing as the planned and supervised process of dose reduction or stopping of medicines that might be causing harm, or no longer be of benefit. It is part of good prescribing – backing off when doses are too high, or stopping medicines that are no longer needed.

In addition, the definition of medicines optimisation empowers patients and the public to make the most of their medicines (Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2013).

Deurden et al (2013) in the King's Fund document Polypharmacy and medicines optimisation - Making it safe and sound introduced the concept of appropriate and inappropriate polypharmacy:

- Appropriate polypharmacy is defined as prescribing for an individual for complex conditions or for multiple conditions, in circumstances where medicine use has been optimised and where the medicines are prescribed according to best evidence

- Problematic polypharmacy is defined as the prescribing of multiple medicines inappropriately, or where the intended benefit of the medicines is not realised.

Box 1 provides the Prescqipp (2020) definition and advice on deprescribing.

Box 1.Prescqipp definition and advice on deprescribing

- Deprescribing is synergistic with inappropriate polypharmacy and is the process of tapering, withdrawing, discontinuing or stopping medicines to reduce potentially problematic polypharmacy, adverse drug effects and inappropriate or ineffective medicine use by regularly re-evaluating the ongoing reasons for, and effectiveness of medication therapy. This should be done in partnership with the patient (and sometimes their carer) and supervised by a healthcare professional. It can be effective in reducing medication (pill) burden in patients to improve their quality of life while still maintaining control of chronic conditions

- Deprescribing must be done judiciously, with monitoring, to avoid worsening of disease or causing withdrawal effects. This needs careful discussion on an individual basis to gain patient understanding and acceptance. It may be helpful to use different terminology for patients. Treatment and care should take into account individual needs and preferences. People who use health and social care services should have the opportunity to make informed decisions about their care and treatment, in partnership with their healthcare professionals and social care practitioners. It is recognised this is a complex process, not a single act, involving multiple steps.

Source: Prescqipp, 2020

Deprescribing as a movement in older adult care

The number of medicines prescribed per person has increased significantly over the past few decades.

In older adult care, the process of deprescribing has developed as a strategy to reverse the potential harm to older adults of receiving too many inappropriate medicines. Many studies have been published about medicine reduction programmes and their success (or not) in reducing polypharmacy. In a review of 132 papers, which included 34, 143 participants aged 73.8 ± 5.4 years, Page et al (2016) found that, for non-randomised studies, deprescribing polypharmacy was shown to significantly decrease mortality. However, this was not statistically significant in the randomised studies. Many of the studies showed that by deprescribing, prescribers were often able to improve patient function, generate a higher quality of life, and reduce bothersome signs and symptoms.

Deprescribing in older adults has become international, and there are a number of websites that provide algorithms and tools to support the process (Box 2) However, there has been limited work to test the validity of these tools in the mental health setting and the tools that do involve psychotropics are usually in the context of elderly people with dementia.

Box 2.Useful deprescribing websites

- Australia: NSW Health Translational Research Grant Scheme 274http://www.nswtag.org.au/deprescribing-tools/

- Canada: The Canadian deprescribing networkhttps://www.deprescribingnetwork.ca) and Deprescribing.org (https://deprescribing.org)

- USA: US Deprescribing Research Networkhttps://deprescribingresearch.org/network-activities/data-and-resources

How is deprescribing relevant in mental health?

Overprescribing or inappropriate prescribing has also become an issue for mental health care. The issues include:

- The rise in antidepressant use: for the fourth successive year antidepressants saw the greatest numeric rise of all British National Formulary (BNF) therapeutic areas for prescription items dispensed in the community in England in 2016, according to a report published by NHS Digital (2017). The report stated that the number of antidepressant items prescribed more than doubled in the last decade (increased from 31.0 million to 64.7 million)

- The continued use of benzodiazepines and Z hypnotics: Davies et al (2017) estimated that more than a quarter of a million people in England are likely to be taking highly dependency-forming hypnotics far beyond the recommended time scales

- The increased consumption of pregabalin: with 5.5 million prescriptions written in UK in 2016 pregalalin has been dubbed the ‘new Valium’ by the Guardian (Marsh, 2017)

- Trends in mental health prescribing towards using multiple psychotropics: a paper from Norway on multiple psychotropic medicine prescribing in older adults showed 41% (n = 4739) of residents of 129 Norwegian nursing homes, were exposed to multi-psychotropic prescriptions (Gulla et al, 2016).

However, campaigns such as ‘Stopping the overmedication of people with a learning disability, autism or both’ (STOMP) (NHS England, 2016) and the antipsychotics in dementia programme ‘The Right Prescription’ (Dementia Action Alliance, 2011), have brought into focus the lack of attention being paid to stopping psychotropic medicines that are neither necessary nor serve a positive purpose.

NHS England (2016) and the antipsychotics in dementia programme (Dementia Action Alliance, 2011) have brought into focus the lack of attention being paid to stopping psychotropic medicines that are neither necessary nor serve a positive purpose.

How is deprescribing of mental health medicines different?

Much effort has been expended in mental health care on demonstrating the benefits of continuing psychotropic medicines and trying to encourage the person to remain on them to prevent relapse of a long-term mental health condition. Fewer studies have been conducted to investigate which psychotropic medicines can safely be stopped without leading to a relapse of the condition, and to find the best time and way to stop them. When people relapse with a severe mental health illness, the failure to adhere with the prescribed medicine is commonly seen as a contributory factor. It is likely with many mental illnesses that if the person reports as well and the symptoms are not troubling them, there will be an expectation to continue the treatment. However, there are other factors to consider.

There are many clinical trials comparing outcomes for people who remain on medicines and those that don't; particularly, trials with antipsychotics being used in people with a diagnosis of psychotic illness. For example, a 2012 Cochrane meta-analysis included 65 trials and showed that maintenance therapy of antipsychotics after remission reduced the risk of relapse more than twofold (27% relapse rate with maintenance treatment versus 64% relapse in a year without) (Gupta and Cahill, 2016). Another recent systematic review addressed the long-term effects and also found that continuation of antipsychotics was more effective than treatment discontinuation or intermittent/guided discontinuation in preventing relapse (Karson et al, 2016). These support the view that the outcome will be generally poorer for those who stop their medicines. However, although many mental health diagnoses are regarded as lifetime or very long-term, the circumstances of the person's life may change or the basis of the diagnosis may be looked upon differently with time.

Fear of a mental health relapse

Prescribers may be concerned that the patients' symptoms of a mental health illness will return and the person will relapse if the mental health medicine is reduced or stopped. It is important to invest time discussing the issue of a mental health relapse and its potential consequences with all the parties involved before embarking on a medicine reduction. Fear of relapse upon reduction of a mental health medicine is a major issue and reducing psychotropics may be seen as much more risky than dose reductions in other therapeutic areas. Rather than avoid the issue of relapse, it should be the first issue to confront, asking such questions as ‘how will the person manage if there is a return of the symptoms?’ and ‘what has changed in the person's life that can enable them to cope without the medicine?’.

Attitudes of mental health professionals towards deprescribing medicines

The attitude of the prescriber will inevitably influence the preparedness to embark on deprescribing. De Kuijper and Hoekstra (2017) undertook a large study investigating physicians' reasons not to discontinue long-term off-label antipsychotics in people with a learning disability. Of the 3299 clients of six large service providers, the prevalence of antipsychotic use was 30%. Overall, physicians were willing to discontinue their antipsychotics in only 51% of cases, varying from 22% to 87% per service provider. This was more likely for patients in ‘a living situation with care and support’ and for whom the prescription was for ‘challenging behaviour’. The main reasons for not discontinuing the antipsychotic were concerns for symptoms of restlessness, the presence of an autism spectrum disorder, previously unsuccessful attempts to discontinue and objections against discontinuation by others. Reasons for physicians' decisions not to discontinue the off-label use of antipsychotics varied between the service providers.

Healthcare professionals' time pressures

The process of deprescribing often takes considerable healthcare professional time. This has been identified as a common barrier for deprescribing in primary care (Duncan et al, 2017). Deprescribing mental health medicines takes potentially longer than for some other medicines, as most should not be stopped suddenly or abruptly.

If a person with hypertension has made changes to their lifestyle and wants to reduce or stop their antihypertensive medicines, the deprescribing process can probably be completed relatively quickly, which will not take up a lot of the clinicians' time. However, for a person on a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressant wanting to stop, the process may take significantly longer, over several weeks, and more than one appointment, tying up much of the prescriber's or team's time.

Logistics and practicalities

In the UK, healthcare policy has encouraged the sharing of prescribing between specialists and general practitioners. Once the person is stable, they are likely to be discharged to the care of the general practitioner. Studies, including that by de Kuijper and Hoekstra (2017), have shown that many general practitioners lack the confidence to undertake the reduction of psychotropic medicines without significant guidance and support from a specialist. This is a great opportunity for pharmacist prescribers working with GP practices in primary care to use their expertise in medicines optimisation. Agreeing the logistics of appointments and stages in medicine reduction can sometimes be difficult.

If the deprescribing is to be led by the specialist, but the prescribing is undertaken by the general practitioner, good communication and agreement of both parties is important.

Tools for withdrawing psychotropic medicines

There are a number of tools to support deprescribing. Some of the most well-known tools for identifying medicines or specific patients likely to require a deprescribing review are described in Table 1. However, the guidance on Medicines Optimisation from the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) identified the need for more research to evaluate the available tools and systems, many of which have not been evaluated in mental healthcare settings (NICE, 2015).

Table 1. Tools that support deprescribing

| Tool | Description |

|---|---|

| Beers (2012) criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults | The original prescribing indicator reference. In some respects the 66 indicators are US specific. There are regular updates of the 1991 indicators; the indicators have been tested in a variety of situations worldwide (Beers, 2012) |

| A pharmacist-led information technology intervention for medication errors (PINCER) Indicators | 10 UK indicators validated in general practice. The PINCER trial demonstrated the effectiveness of a pharmacist-led IT-based intervention to reduce hazardous prescribing. Odds ratios for error were significantly lower in intervention grp (0.51 to 0.73) (Avery AJ et al, 2012) |

| Royal College of General Practice (RCGP) indicators | 34 prescribing safety indicators developed and designed for use in UK general practice. Using a similar process, an updated list of 56 indicators has recently been identified (Avery AJ et al, 2011) |

| Scottish – inappropriate prescribing to vulnerable patients | 15 RAND UCLA-derived indicators that were developed in Scotland and tested on general practice data from 1.7 million patients. A composite indicator was found to be the most reliable measure of a practice's performance (Guthria B et a al, 2011) |

| STOPP/START criteria STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Person's Prescriptions) and START (Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment) | 87 indicators developed by consensus methods in Ireland. They have been validated extensively in the UK setting. Many of the STOPP criteria were included in the RCGP indicator set (Gallagher P et al, 2008) |

Undertaking a medicine review requires good clinical skills. NHS Scotland (2020) has published an excellent guide (7 steps to good medication review - a guide to structure the review process), to support healthcare professionals actually undertaking the reviews.

Approaches to withdrawing psychotropic medicines

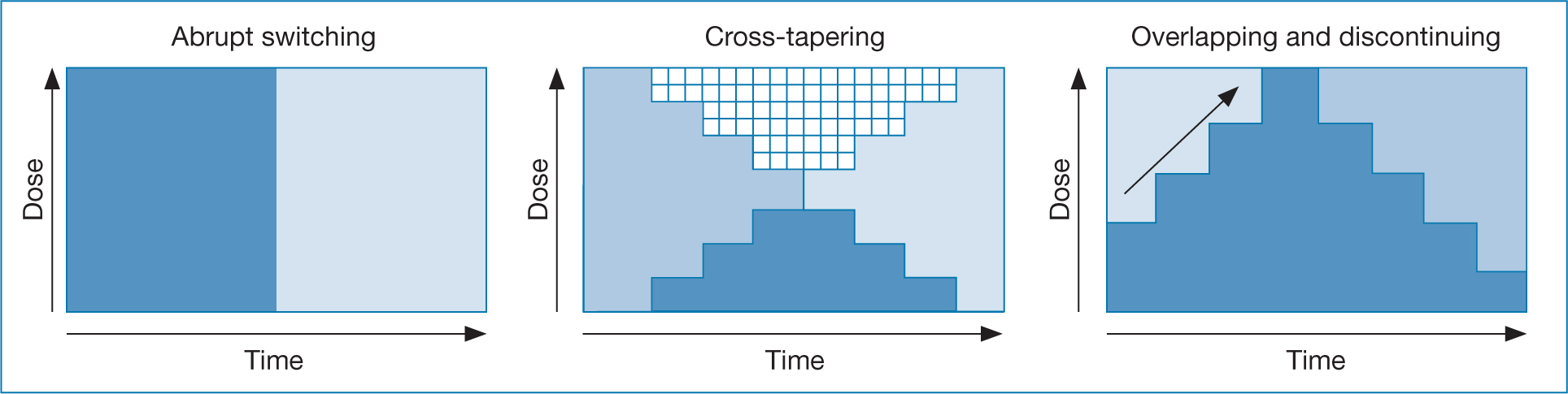

There are a number of approaches to withdrawing psychotropic medicines. These include just stopping, tapering according to a predetermined schedule, substituting an alternative medicine that is easier to reduce and gradual reduction according to the needs and opinion of the patient (Figure 1).

Approaches are broadly based on the theoretical understanding of the pharmacology and pharmacokinetics of the medicines involved.

Guidelines and algorithms

Some guidelines are available. For example, the deprescribing tools provided by the New South Wales Therapeutic Advisory Group (2020) programme. Although they include the following psychotropic medicines, they were developed for use primarily in older adult care:

- Benzodiazepines and Z drugs

- Antipsychotics for the treatment of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia

- SSRIs and Serotonin Noradrenaline Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs)

- Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs).

Although these guidelines are useful aids, the rate of deprescribing should always be shaped by guidelines but directly informed by the patient themselves. If the rate of dose reduction is considered to be too rapid, there should always be the flexibility to change it or even to go back a couple of steps. For some people, this will extend the process.

Withdrawal problems

There is terminology associated with withdrawal problems that may sound confusing. Classically, medicines such as opioids and benzodiazepines are regarded as ‘addictive’, in that the person suffers a degree of craving when they stop the medicine, the withdrawal is associated with a range of symptoms that they did not suffer before, and there is a degree of tolerance to the therapeutic effects of the medicine that may lead to escalating doses. Withdrawal on cessation of a medicine is separate to the experience of rebound symptoms or the return of pre-existing symptoms.

The effect sometimes observed when stopping SSRIs and similar antidepressants is called discontinuation syndrome. These are usually, but not always, short-lived.

Although the extent to which a person undergoing withdrawal of psychotropics suffer actual withdrawal effects is unclear, for the individual concerned the experience is unpleasant and they may require considerable support throughout the process. This adds to the challenge of deprescribing mental health medicines.

The key elements of deprescribing

Reeve at al (2014) undertook a review of the deprescribing process, and identified five key elements for deprescribing in older adults:

- Obtaining a complete medication history

- Identifying medicines that are potentially inappropriate

- Evaluating the possibility of reducing or discontinuing the medicines

- Implementing a plan for reducing or discontinuing the medicines

- Ongoing monitoring documentation and support.

Gupta and Cahill (2016), focusing just on deprescribing in mental health, extended the elements. They felt the extra elements reflected a need for a greater focus on making the process a therapeutic alliance and listening to the patient's experience of and attitudes toward the medicine. They included further additional steps:

- Assessing the timing and context

- Exploring the patient's experience, attitudes and meaning around medication

- Setting a framework for the deprescribing intervention.

Patient advice

Patients will receive advice about whether to continue taking the medicine from many sources. Some offer poor and unhelpful advice. Deprescribing requires a clear consistent message to the patient (Box 3).

Box 3.Clear patient advice about deprescribing

- Avoid stopping suddenly

- Discuss it with someone, ideally your prescriber

- Discuss it with someone you trust

- If possible, seek help from a support group

Risks of stopping suddenly

- Unpleasant withdrawal or discontinuation effects

- Risks to your physical health – with some medicines withdrawal effects can be dangerous if you have been taking them for more than 2–3 months (eg lithium and clozapine)

- Risks to your mental health – your symptoms might come back (relapse)

Source: Choice and medication, 2020

Conclusions

Taking action on polypharmacy is one of the three categories for action mandated by the WHO third global patient safety challenge (medication without harm).

Deprescribing is part of prescribing and a part of taking action on polypharmacy. It focuses on patient safety ensuring that problems are not created by too many medicines, or unnecessary medicines. It leads to optimised medicines use and ultimately better outcome for the patient. The practice of deprescribing should be routinely applied to mental health medicines as much as to other areas.

As polypharmacy becomes more frequent, reviewing this and deprescibing becomes increasingly important. Healthcare professionals have a responsibility to review inappropriate polypharmacy.

There are many barriers to deprescribing in mental health care, and clinicians require good clinical skills to openly discuss medicines adherence and motivation with the patient. This may take some time and more than one consultation. There are numerous tools available to prescribers to help identify suitable patients and medicines to review, however, few are specific to mental health. Deprescribing regimens should be tailored to the individual patient.

Key Points

- Addressing excessive polypharmacy is one of the three categories for action mandated by the WHO third global patient safety challenge (medication without harm). Deprescribing is a part of that challenge.

- Deprescribing in older adult care is part of prescribing, focuses on patient safety and leads to optimised medicine use and better outcomes for the patient.

- Deprescribing in mental health care is less developed. It involves good clinical skills to discuss medicine adherence and motivation openly with the patient, may take time and needs to be tailored to the individual patient.

CPD reflective questions

- What is my attitude towards deprescribing of psychotropic medicines?

- How confident do I feel about taking someone off an antidepressant?

- Do I know how long my patients remain on psychotropic medicines?

- Is multiple psychotropic prescribing a feature of my prescribing?

- When my patients request stopping their psychotropic medicines do I know where to find information that will help them?