The British National Formulary (BNF) and BNF for Children (BNFC) app give quick access to reliable, practical, evidence-based information that supports safe prescribing (BNF Publications, 2022a). It offers several advantages for prescribers, the main one being that, unlike the print publications, clinical content is updated every month (Joint Formulary Committee (JFC), 2021). The BNF is updated twice a year, and the BNFC is updated annually (BNF Publications, 2022b); digital publications are preferable for prescribers, to assure clinical currency and reduce medicolegal risk. While the content of BNF Online is updated monthly (BNF Publications, 2022c), the BNF app is fully functional offline (BNF Publications, 2022a), making it ideal for home visits and ward rounds.

The BNF app includes information on how to use BNF Publications; however, it relates to BNF Online. This article is a practical guide to empower prescribers to use the BNF app more effectively. It focuses on accessing BNF app content from mobile telephones; images are taken from an iOS device. Developing the skills to efficiently navigate the BNF app enables prescribers to harness its wealth of information to support safe practice.

Accessing the British National Formulary app

The app can be downloaded from the Apple App Store for iOS devices and the Google Play Store for Android devices (BNF Publications, 2022a).

Navigating the British National Formulary app: an overview

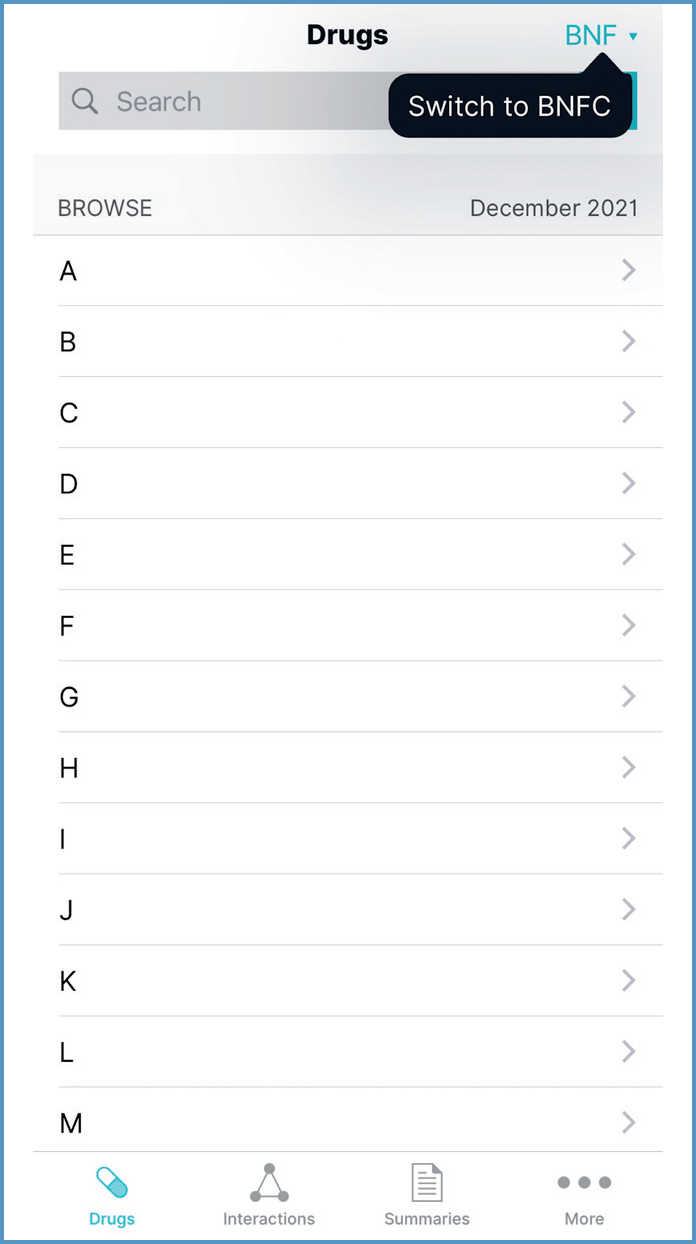

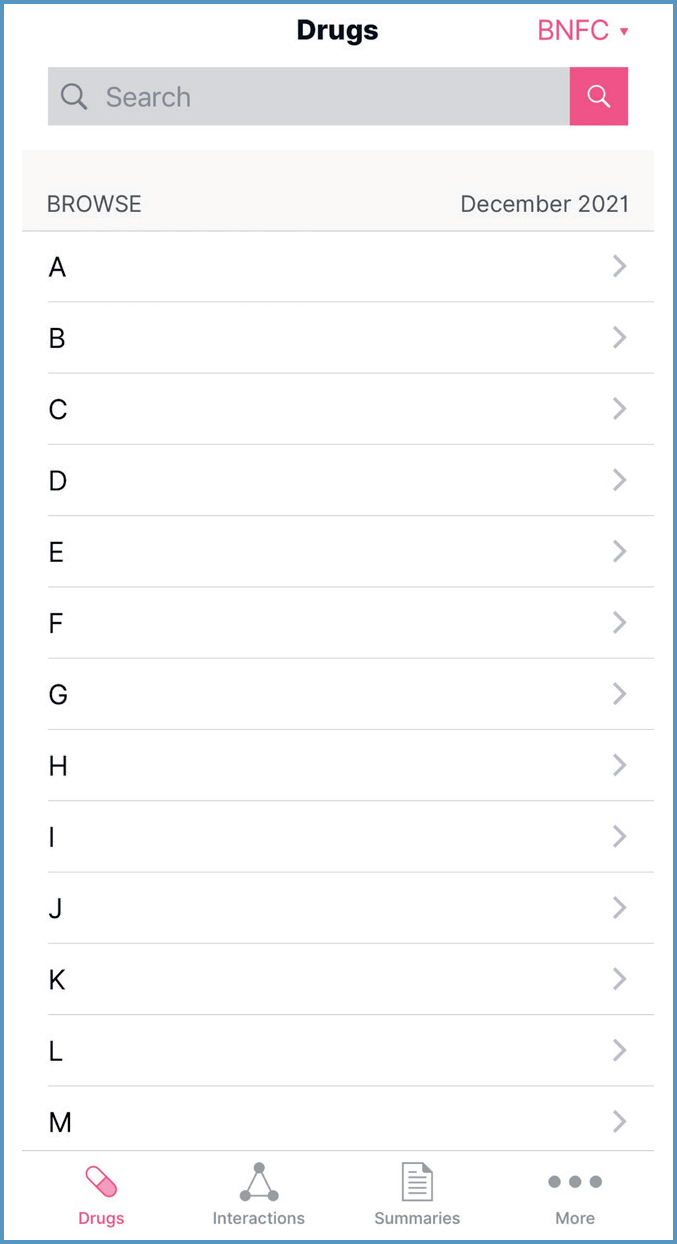

Switching between British National Formulary and British National Formulary for Children To switch between BNF and BNFC content, use the dropdown in the top right-hand corner of the app (Figure 1). BNF content is colour-coded blue to represent adults; BNFC is colour-coded pink to represent children (Figure 2) (BNF Publications, 2022d).

Main menus

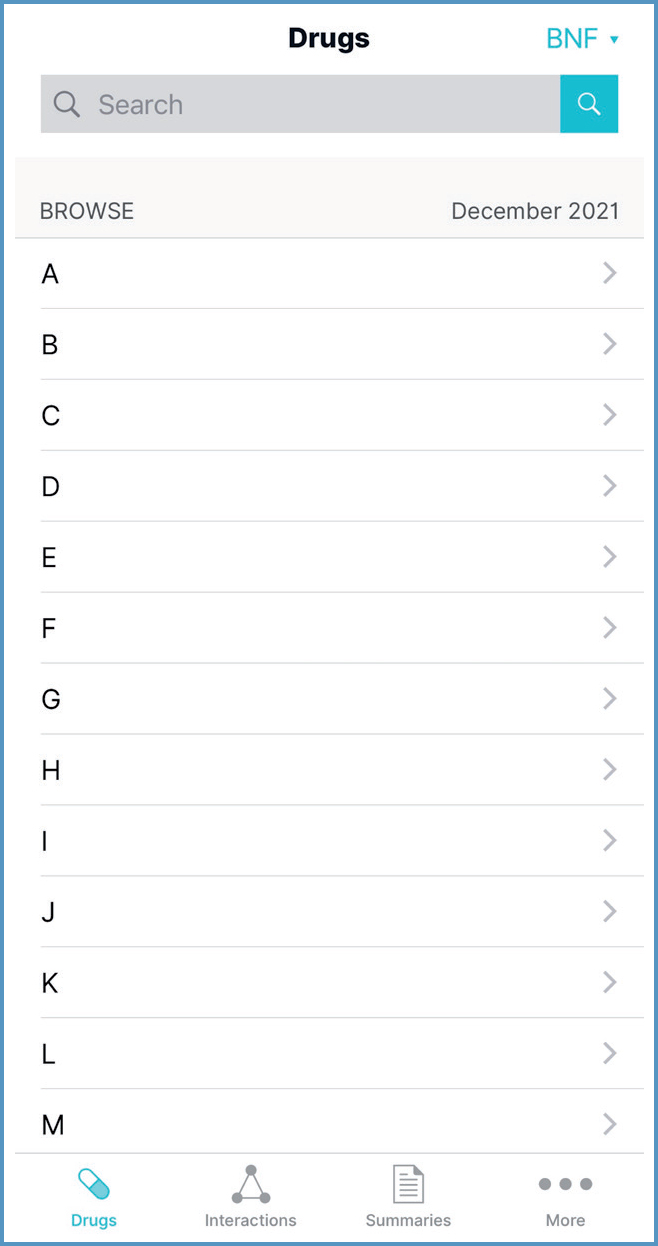

The four main sections of the BNF can be accessed from the menus running across the bottom of the app:

- Drugs

- Interactions

- Summaries

- More.

Drugs is the default menu when opening the app. The option selected is highlighted in blue (Figure 3) when using BNF content, and pink when using BNFC content, adhering to the general colour coding.

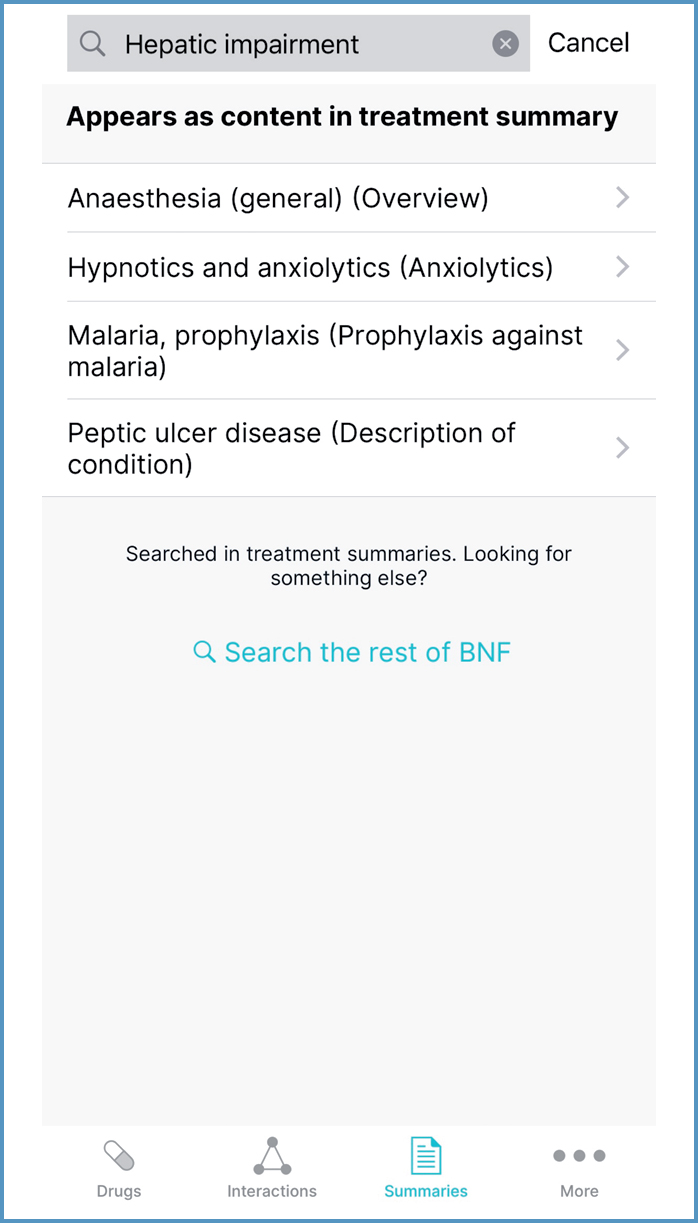

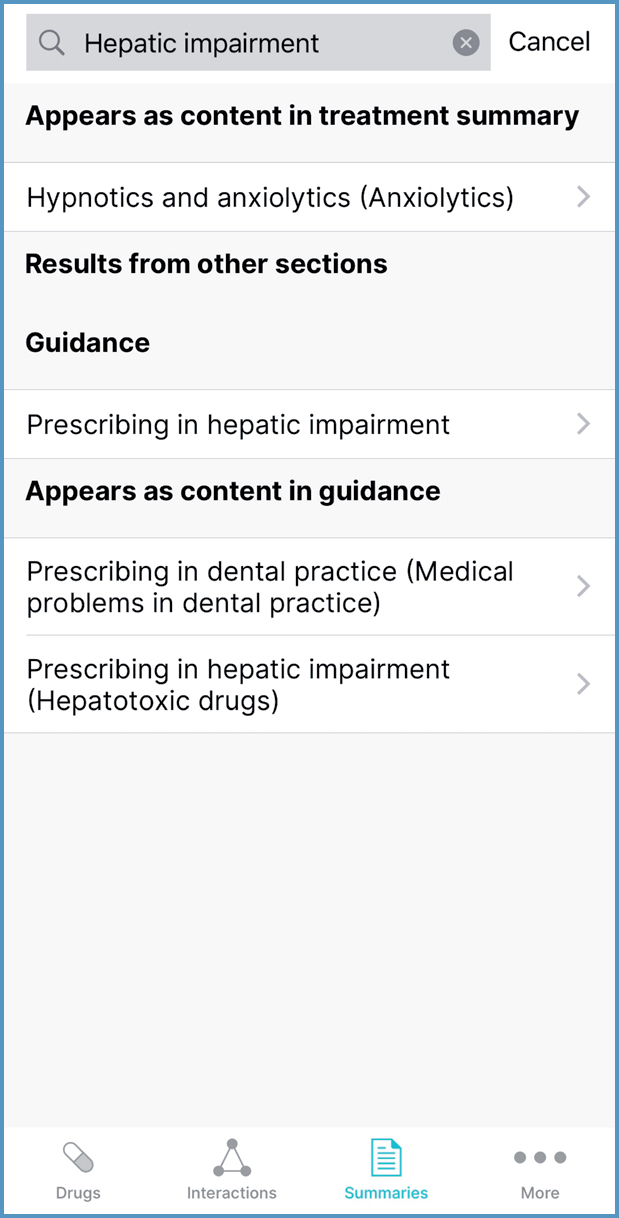

In the Drugs and Summaries sections, prescribers can expand their search by selecting ‘Search the rest of BNF’ or ‘Search the rest of BNFC’ from below the search results. For example, searching ‘Hepatic impairment’ in the Summaries section shows that this term appears in four treatment summaries (Figure 4). Expanding the search shows that there is guidance on prescribing in hepatic impairment (Figure 5).

Drugs

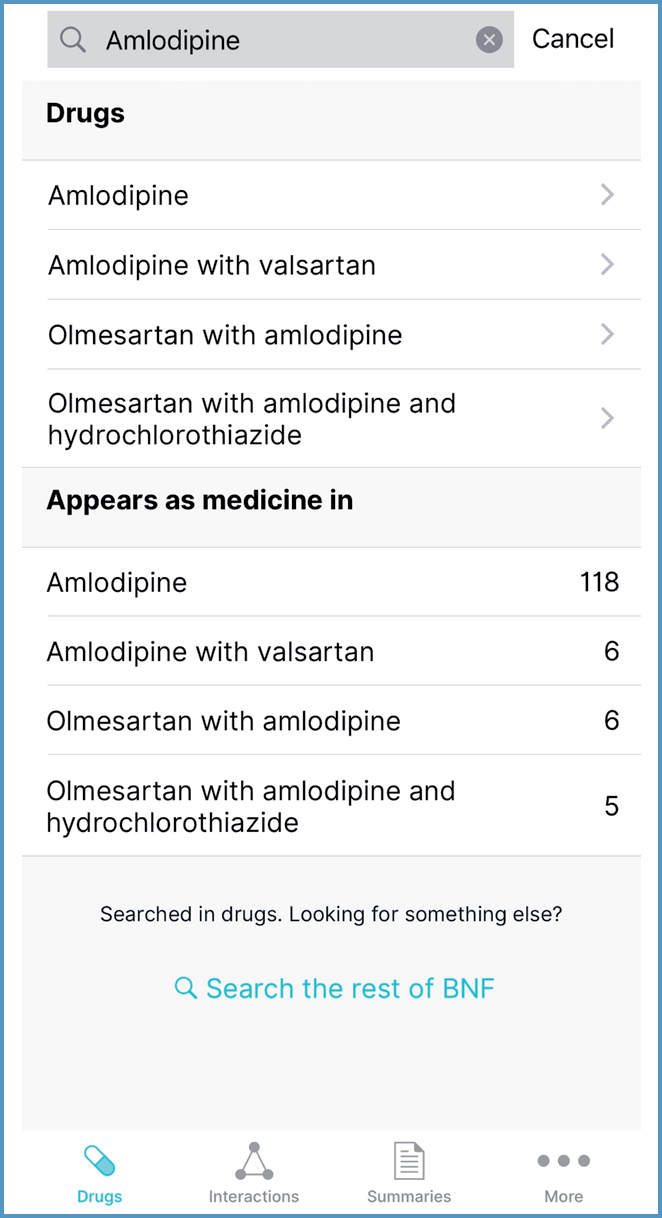

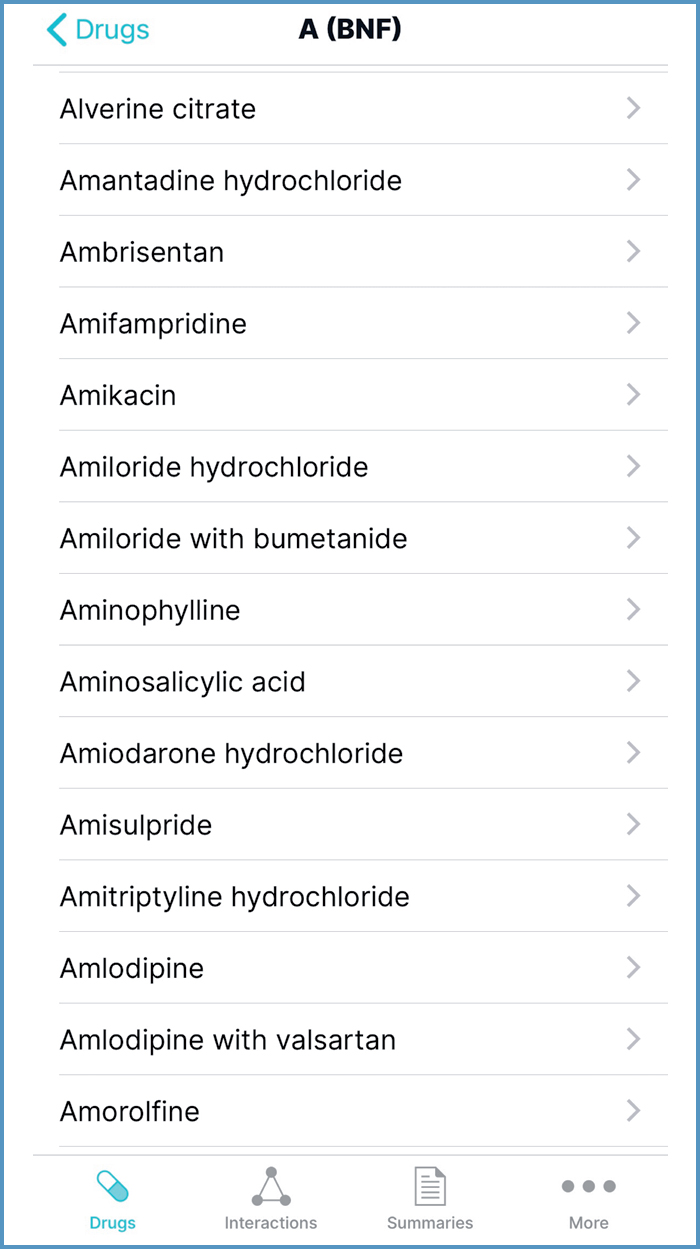

Drug monographs can be accessed using the search function (Figure 6) or the A to Z list (Figure 7). Within each drug monograph, a menu facilitates navigation to particular sections.

Interactions

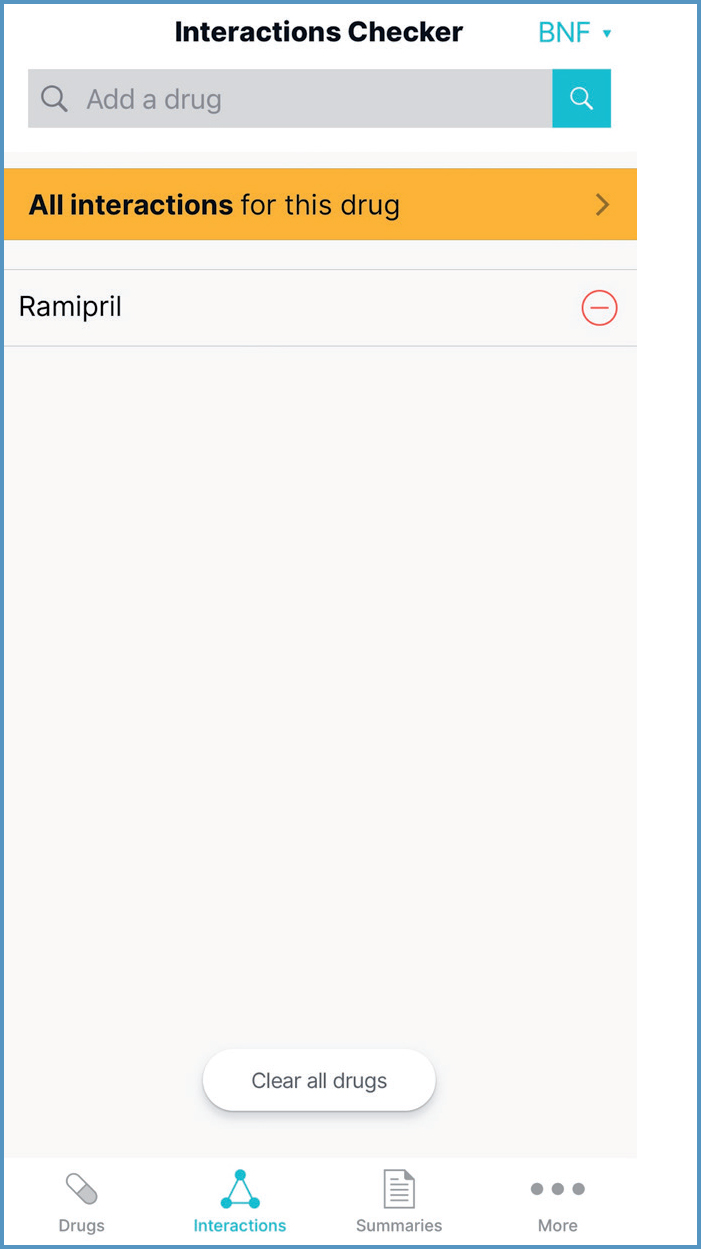

The Interactions Checker tool can be accessed by selecting Interactions from the menus running across the bottom of the app. It can also be accessed from within the drug monograph by selecting the Interactions symbol in the top right corner, and then selecting ‘Open in Interactions Checker'. This populates the Interactions Checker with the drug (Figure 8).

Summaries

Treatment summaries can be accessed using the search function or via alphabetical list. They are divided into categories based on aspects of medical care (such as vaccines) or drug use related to a particular body system (for example, the nervous system) (JFC, 2021).

More

Information within the following sections can be accessed using the search function or menu:

- Medical devices

- Borderline substances

- Wound care.

Information within the Guidance, Nurse Prescribers’ Formulary and About sections is accessed from a menu.

Using the British National Formulary to support safe prescribing

Drugs

Where possible, all information about a drug is contained in its monograph, to ensure prescribers are not missing important information (Callachand, 2018). A drug monograph can have over 20 sections; they always appear in the same order (Callachand, 2018), but are only included where relevant information is identified (Bellerby and Needham, 2016; Callachand, 2018; JFC, 2021). For example, the ibuprofen monograph has 19 sections, but the loratadine monograph has only ten. Prescribers should look at the whole monograph and consider all relevant content (BNF Publications, 2022e).

Drug class monographs are created when there is substantial common information (Callachand, 2018). Class monograph information is presented within each relevant drug monograph (Callachand, 2018). For example, side effects common to all systemic beta-adrenoceptor blockers are presented in the bisoprolol monograph. This information may help prescribers determine the appropriateness of switching to an alternative drug in the same class.

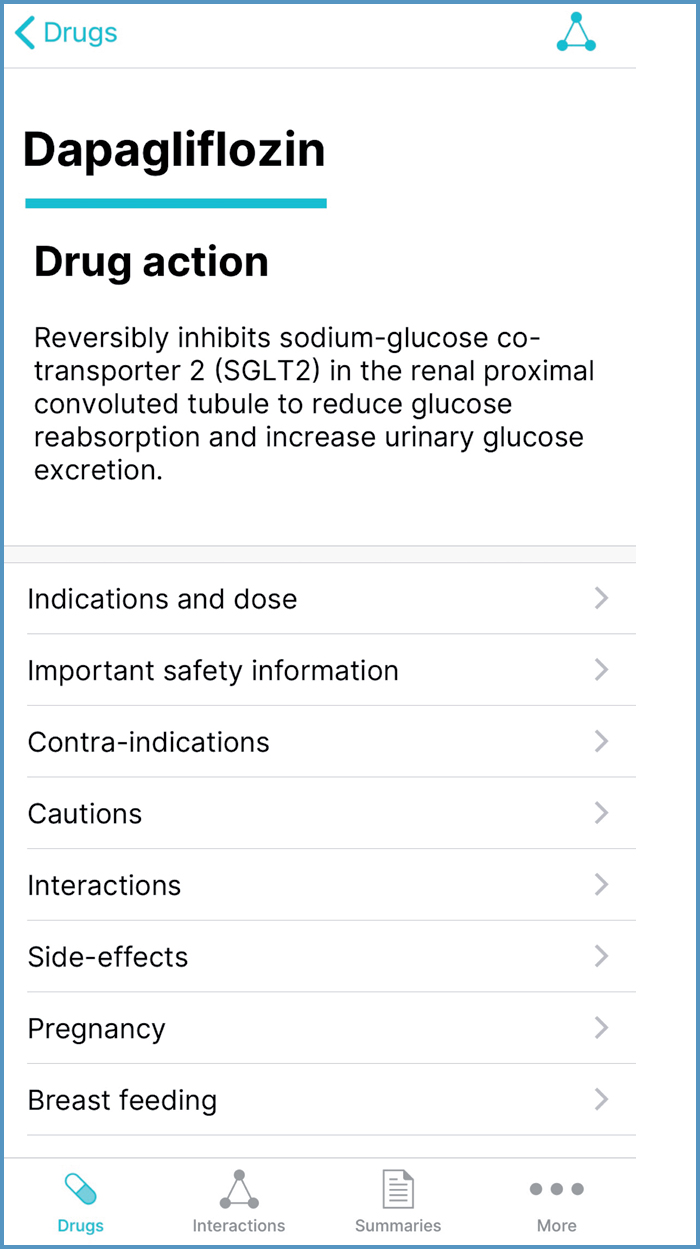

Drug action statements

Drug action statements are located at the top of the drug monograph (Figure 9). They outline pharmacodynamic properties (ie, the effect(s) a drug has on the body) (Robertson, 2017); this could be useful when explaining how a medicine works.

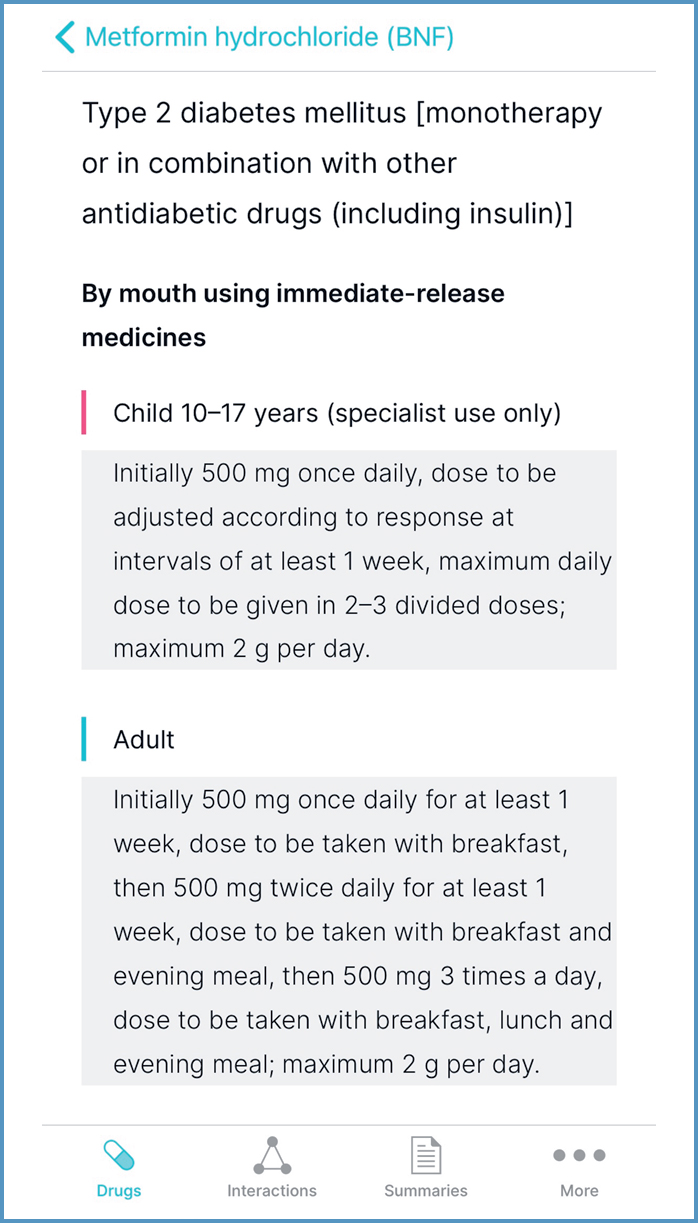

Indications and dose

Indications and dose is the first menu item, which corresponds with the main uses of the BNF (Callachand, 2018; JFC, 2021). Prescribers should first identify the indication and then the route, followed by age range and, finally, dose regimen. Indications should be cross-referenced with the ‘Unlicensed use’ section. Information on dose should be read in conjunction with the ‘Hepatic impairment’ and ‘Renal impairment’ sections, if clinically relevant.

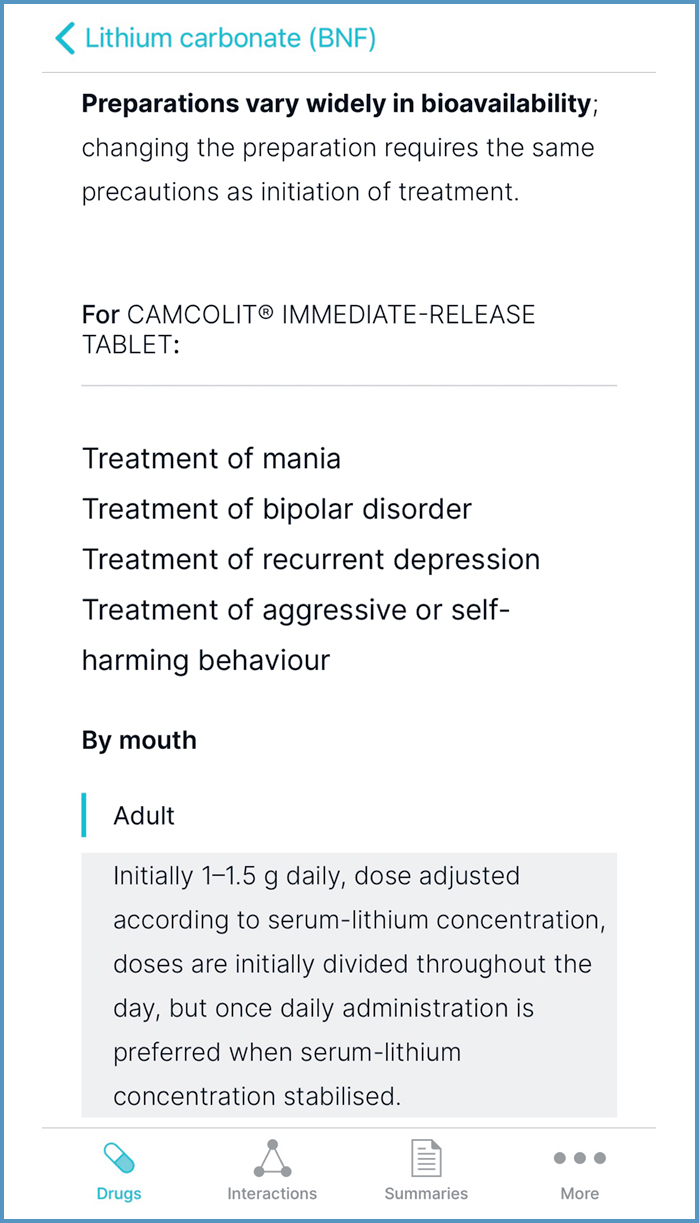

If doses vary between formulations, as with metformin immediate-release (IR) and modified-release medicines, these are detailed under a heading relating to route and formulation. Figure 10 shows the dose of metformin IR medicines for treatment of type 2 diabetes, in children 10–17 years and adults. Similarly, if doses vary between preparation, they are detailed under the preparation heading, as seen with lithium carbonate (Figure 11). Lithium carbonate preparations vary widely in bioavailability (JFC, 2021); they should be prescribed by brand (Brennan, 2017; Clinical Knowledge Summaries (CKS), 2021a).

Information on pharmacokinetics, or ‘what the body does to the drug’ (Ritter et al, 2019), can inform prescribing decisions. For example, the statement ‘Consider the long half-life of fluoxetine when adjusting dosage (or in overdosage)” (JFC, 2021) could support a decision to stop fluoxetine 20mg daily, rather than tapering the dose.

Valuable additional dosing information, which may be found at the end of this section, is shown in Table 1 (BNF Publications, 2022e).

Table 1. Additional dosing information, which may be found at the end of the ‘Indications and dose’ section. Adapted from CKS (2021b), JFC (2021) and BNF Publications (2022e)

| Dosing information | Value to prescribers | Example |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Dose equivalence and conversion' | Can help safely switch forms | Citalopram4 oral drops (8mg) is equivalent in therapeutic effect to one 10mg tablet |

| ‘Potency' | Enables selection of a suitable preparation for a topical corticosteroid regimen | Mild flare of facial eczema Hydrocortisone 1% cream |

| ‘Dose adjustments due to interactions' | Supports interaction management | Atorvastatin Maximum 10mg daily if concomitant ciclosporin unavoidable |

| ‘Doses at extremes of body-weight' | Minimises risk of excessive dosage in obese people | AciclovirIn obese patients parenteral dose should be calculated on the basis of ideal weight for height |

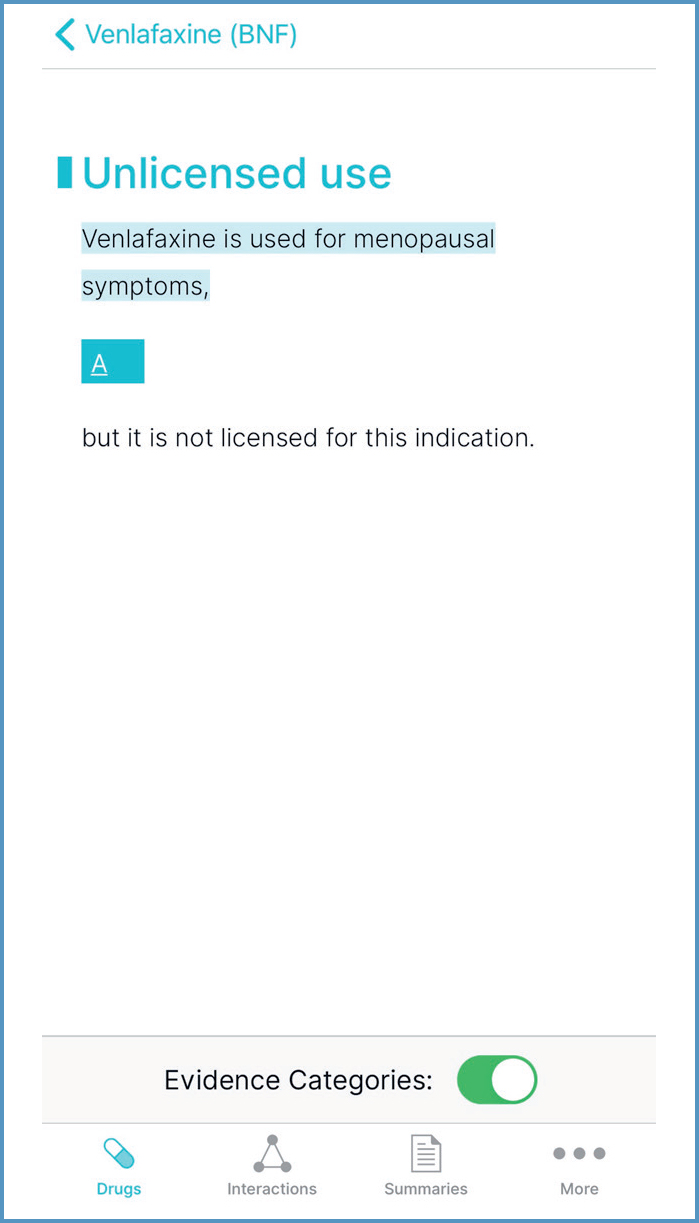

Unlicensed use

Unlicensed use of medicines encompasses use of medicines ‘off-label’ (ie, outside the terms of their UK marketing authorisation (MA)) and use of medicines that do not have a UK MA (General Medical Council (GMC), 2021; JFC, 2021). It alters (and probably increases) the prescriber's professional responsibility (Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), 2009; JFC, 2021). Before unlicensed use, prescribers should consider the following questions (MHRA, 2009; GMC, 2021; Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS), 2021a):

- What are the prescribing rights for my profession?

- Is there enough evidence and/or experience of using the medicine to show safety and efficacy?

Identifying evidence-based treatment options is a competency necessary for all prescribers (RPS, 2021a). BNF recommendations for unlicensed or ‘off-label’ use are graded to reflect the strength of underpinning evidence (Callachand, 2018; JFC, 2021). Grade A is high-strength evidence, such as National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) accredited guidelines; Grade D is very low-strength evidence; and Grade E is a practice point. Evidence Categories can be toggled on/off, as seen in Figure 12.

Important safety information

The ‘Important safety information’ section summarises advice from the MHRA and its independent advisor, the Commission on Human Medicines (CHM). It also outlines risk minimisation measures to avoid an NHS Never Event (NHS Improvement, 2018a).

For example, the methotrexate monograph includes recommendations to avoid the NHS Never Event of ‘overdose of methotrexate for non-cancer treatment’ (NHS Improvement, 2018b) and related MHRA/Committee on Safety of Medicines (CSM) advice (MHRA, 2020).

‘Safe Practice’ information alerts prescribers to ‘look-alike sound-alike’ errors, which are a common cause of medication error (Abdellatif et al, 2007; MHRA, 2018a). For example, ‘Prednisolone has been confused with propranolol; care must be taken to ensure the correct drug is prescribed and dispensed’ (JFC, 2021).

Contra-indications and Cautions

When prescribing a drug for one condition, the impact on any other conditions must be considered. Contra-indications are conditions or circumstances when a drug should be avoided (Bellerby and Needham, 2016). Contra-indications are more restrictive than cautions (JFC, 2021). For example, if a person with asthma develops heart failure, bisoprolol should be avoided; however, if they have chronic obstructive airways disease, bisoprolol may be cautiously introduced (JFC, 2021). Where a caution exists, prescribers should carefully consider the potential for harm (Bellerby and Needham, 2016).

Side effects

The terms ‘side effect’ and ‘adverse drug reaction’ (ADR) are often used interchangeably, but there is a distinction in that side effects can be harmful or beneficial (Yellow Card Centre Scotland and National Education Scotland, 2013). For example, if a person takes amitriptyline for neuropathic pain that is keeping them awake, drowsiness could help them sleep.

Side effects are generally listed alphabetically in order of frequency (JFC, 2021). ‘General side effects’ and ‘Specific side effects’ subsections are used if there are particular side effects associated with the administration route (eg, parenteral hydroxocobalamin) (Bellerby and Needham, 2016). The subsection ‘Side effects, further information’ can help prescribers avoid or manage side effects. For example, the linagliptin monograph recommends discontinuation if symptoms of acute pancreatitis develop (JFC, 2021).

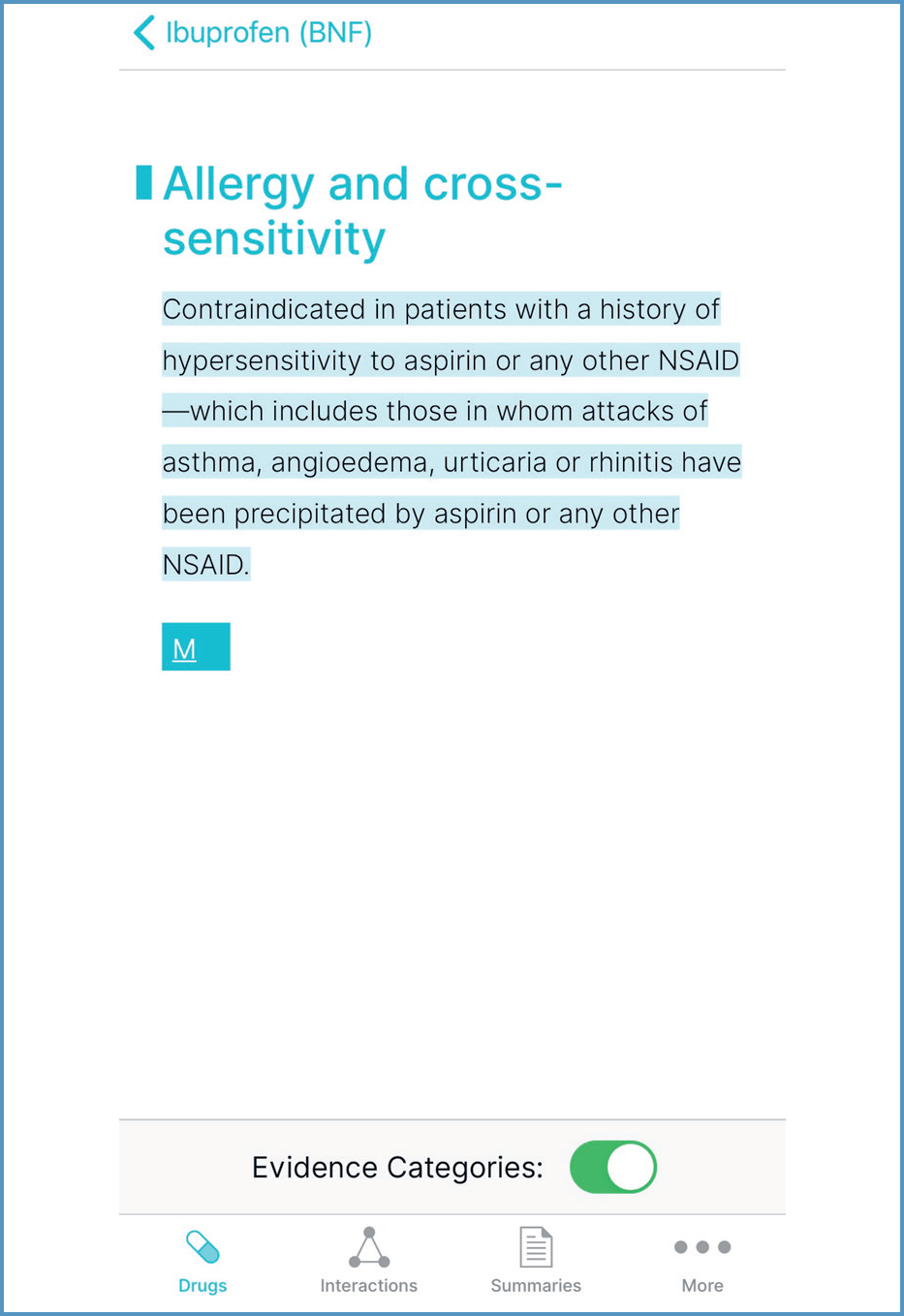

Effects that are likely to have little clinical consequence (eg, transient increase in liver enzymes) are omitted (JFC, 2021). Hypersensitivity reactions are not usually listed, unless the drug carries an increased risk or specific management advice is provided by the manufacturer (JFC, 2021). An example is ibuprofen, as shown in Figure 13.

Prescribers should minimise risk by considering the adverse effect profile of treatment options and factors that may affect a person's susceptibility, such as age (Ferner and Aronson, 2019).

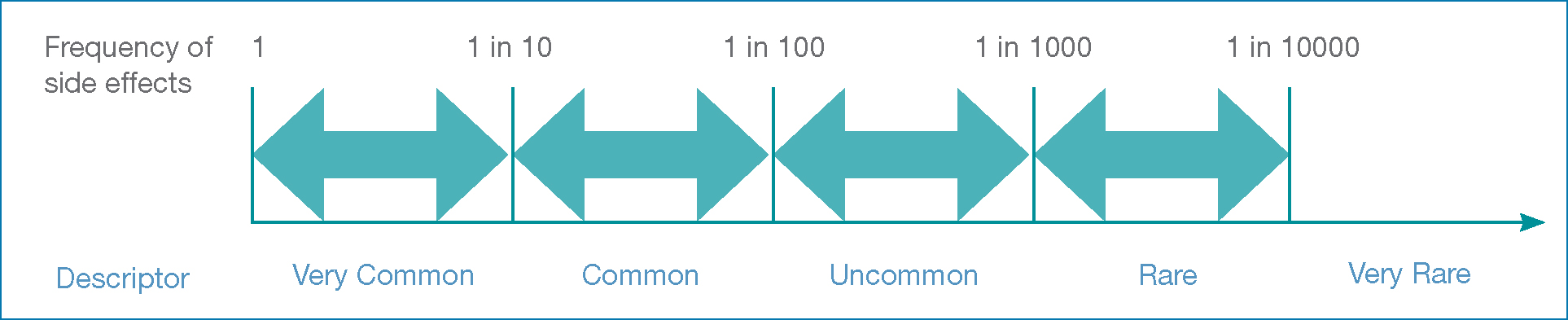

Risk descriptors, such as ‘common', are used in drug monographs. Figure 14 shows the relationship between descriptors and frequency bands. Research shows that people equate these descriptors to risks that are considerably higher (Berry et al, 2003; MHRA/CSM, 2005). These differences in perception are important when communicating risk, because they influence whether people would take medication (Freeman and Recchia 2019). Prescribers have an ethical and legal obligation to ensure people understand the ‘material risks’ of their medication (Freeman and Recchia, 2019).

Allergy and cross-sensitivity

Prescribers should consider this section alongside the person's drug allergy status and the signs, symptoms and severity of any reactions (NICE, 2014a). Advice is provided on appropriateness of using the drug and others that are structurally related. For example, mesalazine is contraindicated in salicylate hypersensitivity.

Contraception and conception

This section provides advice on the need for contraception before, during and after treatment. When prescribing any medicine with teratogenic potential, a woman should be advised of the risks and encouraged to use the most effective contraceptive method for her circumstances (MHRA, 2019). Prescribers may also need to discuss contraception with men. For example, mycophenolate medicines are genotoxic and are excreted in semen (MHRA, 2018b; JFC, 2021).

Pregnancy

The smallest number of the safest medicines, at the lowest effective doses, should be used while preparing for and during pregnancy (Girling, 2019); all drugs should be avoided if possible during the first trimester (JFC, 2021). Drug selection should aim to minimise harm to the mother and baby (Bellerby and Needham, 2016; JFC, 2021). Absence of information in the ‘Pregnancy’ section does not imply safety (JFC, 2021).

Prescribers should empower women to plan pregnancy, according to disease activity and treatment (Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin (DTB), 2017). Continuing medication may be the best option; decisions should be supported by high-quality information and may need specialist advice (see Box 1) (Girling, 2019).

Box 1.Resources for use of drugs in pregnancy and breastfeeding

- Specialist Pharmacy Services Safety in pregnancy: www.sps.nhs.uk/home/guidance/safety-in-pregnancy/

- UK Teratology Information Service: www.uktis.org/

- UK Best Use of Medicines in Pregnancy: www.medicinesinpregnancy.org/

- Specialist Pharmacy Services Safety in breastfeeding: www.sps.nhs.uk/home/guidance/safety-in-breastfeeding/

- UKDILAS: www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/ukdilas/

- USA Toxicology Data Network Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed): www.toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/newtoxnet/lactmed.htm

- HalesMeds: www.halesmeds.com/

- The Breastfeeding Network Drugs in Breastmilk Service: www.breastfeedingnetwork.org.uk/detailed-information/drugs-in-breastmilk/

- MHRA Use of medicines in pregnancy and breastfeeding guidance: www.gov.uk/guidance/use-of-medicines-in-pregnancy-and-breastfeeding

Breastfeeding

Prescribers should discuss the benefits and risks of medication and, if appropriate, encourage breastfeeding (NICE, 2008). Most medicines are not licensed for use during lactation (Jones, 2021). Information in the ‘Breast-feeding’ section should only be a guide, as it does not contain quantitative data on which to base individual decisions; prescribers should consult supplementary sources or seek guidance from the UK Drugs in Lactation Advisory Service (UKDILAS) (see Box 1) (NICE, 2008; Jones, 2021).

Hepatic and renal impairment

Appropriate drug selection can minimise the potential for accumulation, adverse effects and exacerbation of hepatic or renal disease (Bellerby and Needham, 2016; JFC, 2021). The ‘Hepatic impairment’ and ‘Renal impairment’ sections provide information about drugs that should be avoided or used with caution in hepatic or renal impairment, and associated dose adjustments. For example, the maximum daily dose of pregabalin for the management of neuropathic pain is halved if creatinine clearance is 30–60ml/minute (JFC, 2021). Prescribers may need supplementary information from specialist texts, such as The Renal Drug Handbook.

Pre-treatment screening

This section outlines screening tests needed before starting treatment, such as measuring thiopurine methyltransferase activity before initiating azathioprine (NICE, 2015; Ledingham et al, 2017; Lamb et al, 2019; JFC, 2021). Screening supports shared decision-making by providing information that can reduce the risk of toxicity and anticipate treatment failure.

Monitoring requirements

This section outlines the tests needed before and during treatment; it can help prescribers to formulate a plan to monitor effectiveness and identify adverse effects. For example, liver enzymes should be measured before initiating statins, with measurement repeated within 3 months and at 12 months (NICE, 2014b; JFC, 2021; Khatib and Neely, 2021). Prescribers may need supplementary information from other resources, such as the Medicines Monitoring tool on the Specialist Pharmacy Service website.

Treatment cessation

Prescribers can use this section to inform deprescribing decisions; it outlines the risks of suddenly stopping a drug or making a large dose reduction, such as discontinuation symptoms with antidepressants, in which case a tapering approach may be suggested. Prescribers may need to consult other sources, such as the Clinical Knowledge Summaries and MedStopper websites.

Effect on laboratory tests

Prescribers need to be aware when a drug may affect a test, to facilitate communication with the laboratory and interpretation of results. For example, finasteride decreases serum concentration of prostate-specific antigen, and reference values may need adjusting (JFC, 2021).

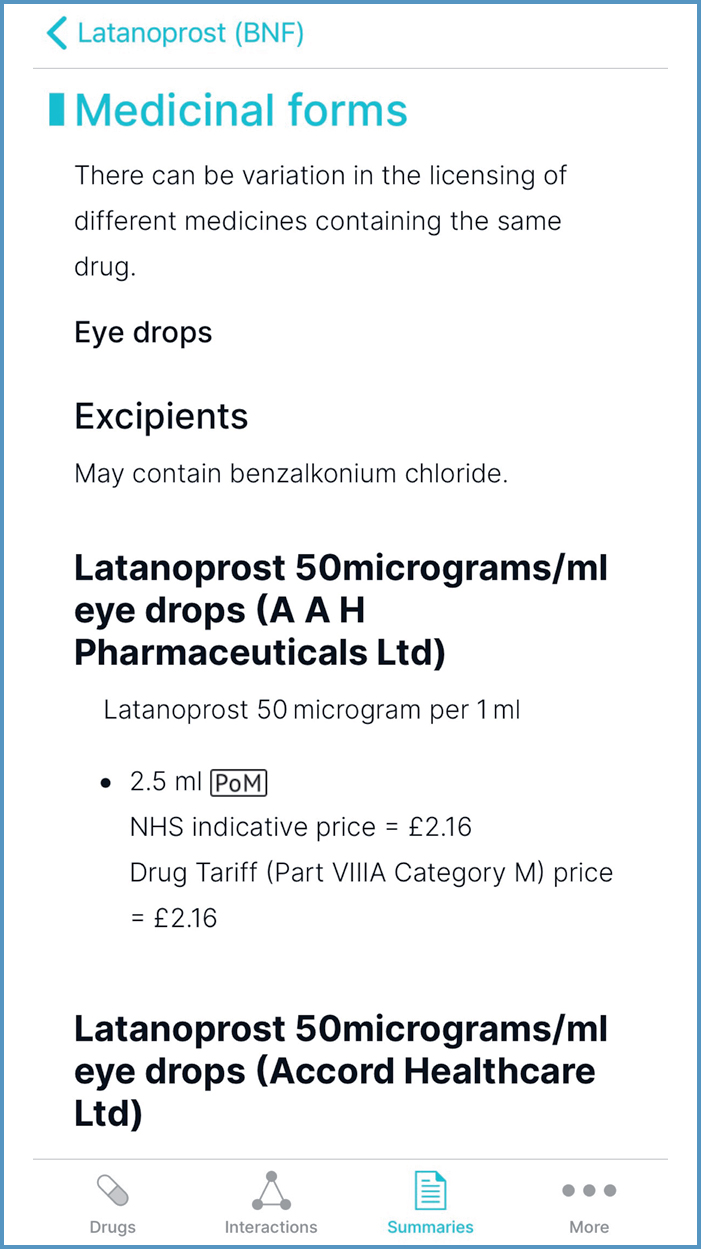

Medicinal forms

Information on selected excipients, including allergens such as gluten, is detailed below the formulation, as shown in Figure 15.

The black triangle symbol, next to the product name, identifies new medicines for which prescribers should report all ADRs (MHRA, 2021; JFC, 2021); an example is ertugliflozin.

Interactions

The Interactions Checker tool enables identification of potentially serious issues between drugs (Callachand, 2018); background information can be accessed via the ‘About interactions’ link.

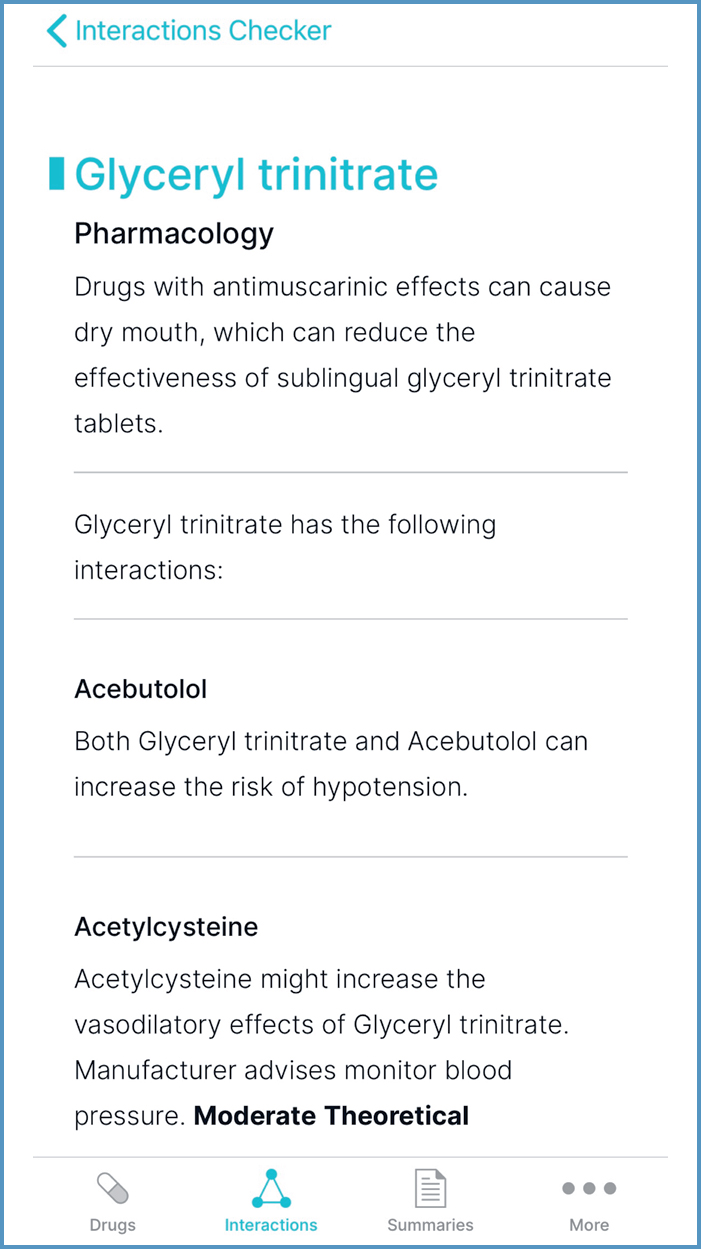

Entering all or part of a drug name into the search field and then choosing the plus icon next to the drug name adds it into the Interaction Checker; selecting the yellow banner reveals a list of all interactions for that drug. An advantage of this strategy is provision of information to support safe prescribing. Examples include:

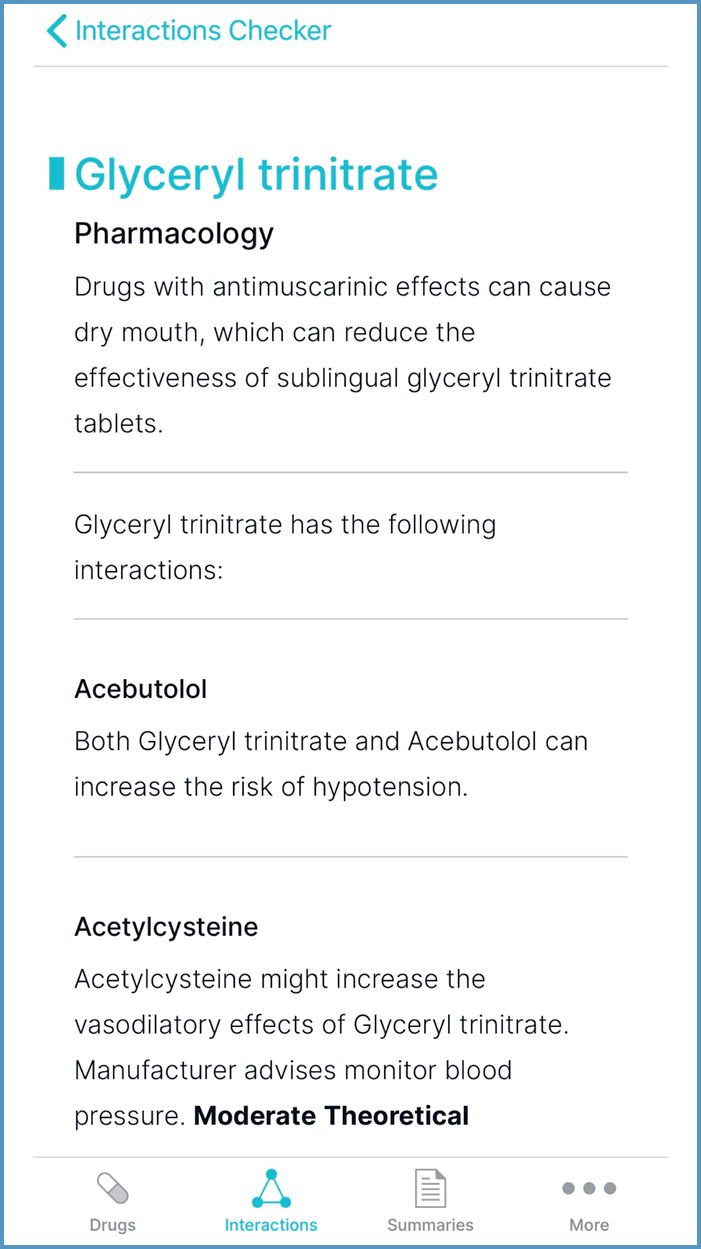

- ‘Route-specific information', shown in Figure 16, can be helpful to determine the likelihood of interactions with topical preparations

- ‘Pharmacology', shown in Figure 17, can inform the choice of formulation

- ‘Separation of administration’ can inform timing of doses, to optimise absorption

- ‘Food and lifestyle’ can inform dietary intake and dose adjustment. For example, dairy products decrease exposure to oxytetracycline; this can be cross-referenced with ‘Cautionary and advisory labels', in ‘Medicinal forms', to determine that milk can be consumed 2 hours before or after taking oxytetracycline (JFC, 2021). An example of dose adjustment is reducing the dose of olanzapine if a person stops smoking. Prescribers may need further information (for example, the Q&A by Hodgson (2020)) on the size of dose reduction and monitoring.

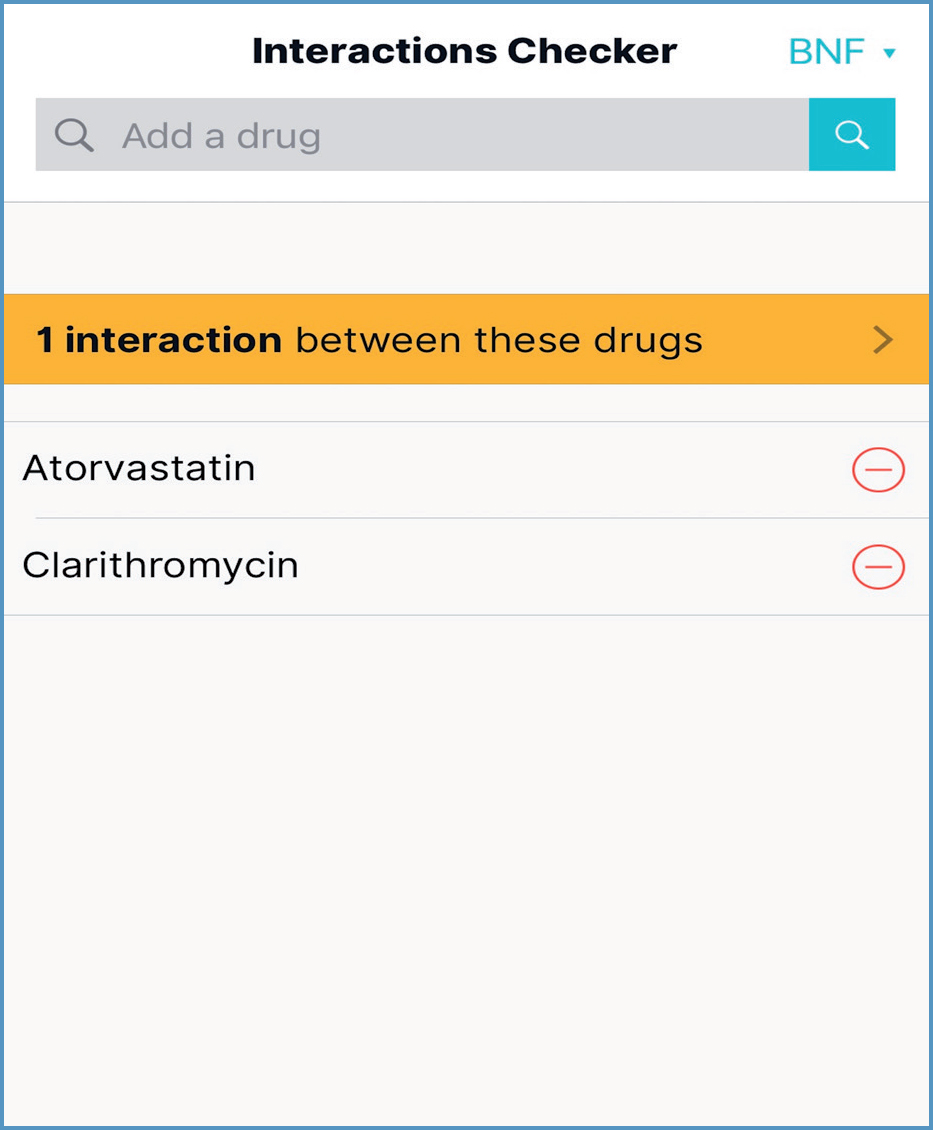

It can be faster to add all prescribed medication; the yellow banner then states the number of interactions between the drugs, as shown in Figure 18. When selected, interaction information is displayed. However, when using the example of glyceryl trinitrate and the antimuscarinic solifenacin, there are no interactions, so ‘Pharmacology’ information would not be displayed.

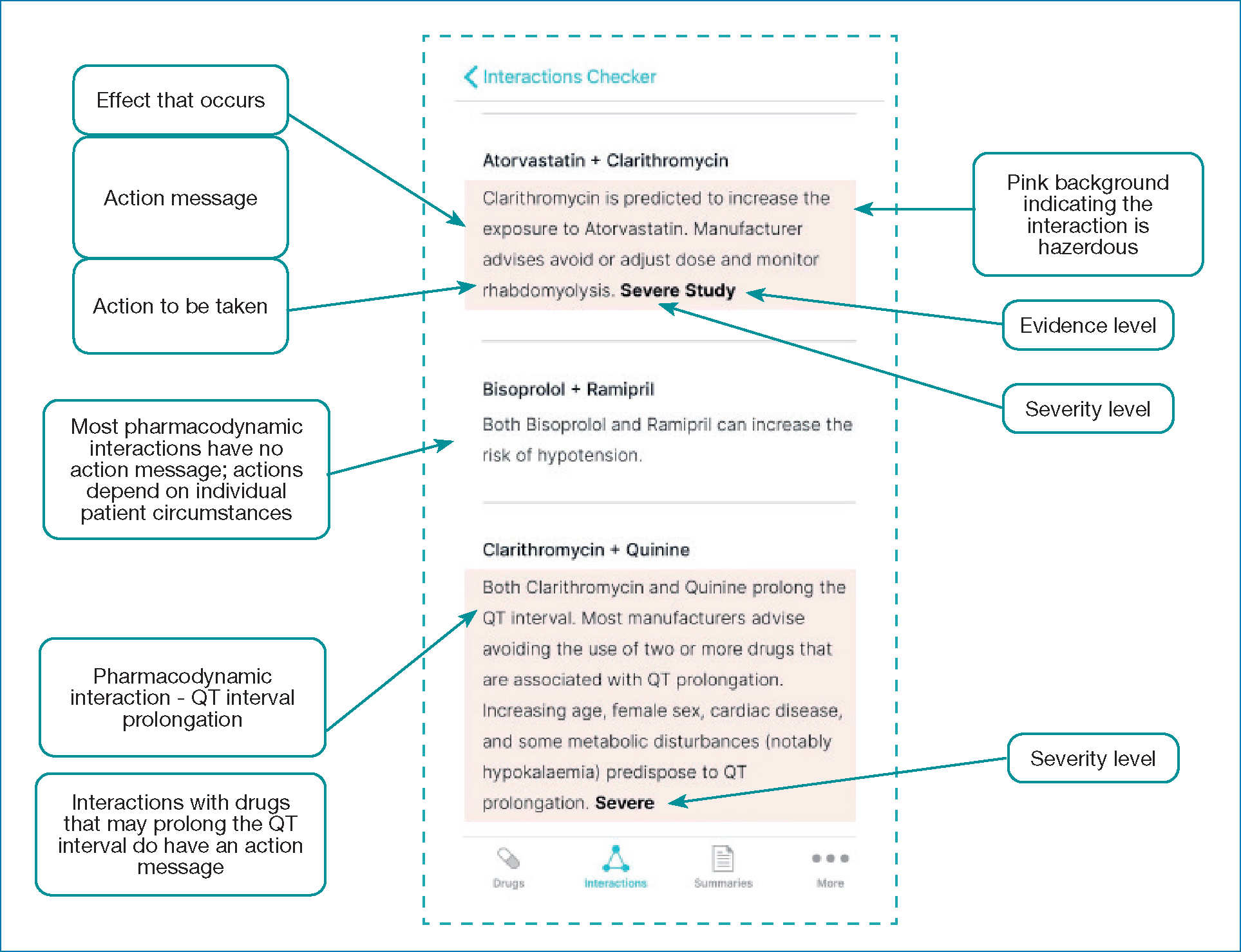

Figure 19 illustrates the key elements of interaction content:

- Action message: describes the effect that occurs and the action to be taken (JFC, 2021)

- Severity level: helps prescribers determine the clinical significance of an interaction

- Evidence level: rating to indicate the weight of evidence behind the interaction.

Pharmacodynamic interactions occur between drugs that have similar or opposing pharmacological actions or side effects. For example, bisoprolol and ramipril both lower blood pressure. Action messages are not usually included, because management needs to be individualised. For example, if ramipril is indicated solely for heart failure, adding bisoprolol could lead to hypotension; this risk needs to be balanced with benefits, such as symptom improvement and prolonged survival (Chatterjee et al, 2013). The exception is drugs that may prolong the QT interval, which can lead to a life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia (Stobo, 2020); therefore, most manufacturers advise avoiding combined use (JFC, 2021).

Potentially harmful drug combinations should either be avoided or the interaction should be managed to allow safe use (for example, by dose adjustment). A guiding principle is: ‘If it's pink, have a think!'.

Summaries

Guidelines are likely to be the primary references underpinning clinical management. Complementary information within treatment summaries includes:

- Dosing equivalents, summarised in Table 2

- Prescribing in patients with stoma, located within ‘Stoma care'.

Table 2. Summary of information on dosing equivalents, located within Treatment summaries. Adapted from JFC (2021)

| Subject | Treatment summary | Search term |

|---|---|---|

| Equivalent doses of benzodiazepines | Hypnotics and anxiolytics (Dependence and withdrawal) | Equivalent |

| Equivalent anti-inflammatory doses of corticosteroids | Glucocorticoid therapy (Glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid activity) | Equivalent |

More

Guidance

Topics of particular relevance to prescribers are shown in Table 3. A number of useful tables, located within Guidance, are summarised in Table 4.

Table 3. Guidance of particular relevance to prescribers

| Topic |

|---|

| Adverse reactions to drugs |

| Antimicrobial stewardship |

| Controlled drugs and drug dependence |

| Guidance on prescribing |

| Medicines optimisation |

| Non-medical prescribing |

| Prescribing in breast-feeding |

| Prescribing in children |

| Prescribing in hepatic impairment |

| Prescribing in palliative care |

| Prescribing in pregnancy |

| Prescribing in renal impairment |

| Prescribing in the elderly |

| Prescription writing |

Table 4. Useful tables located within the ‘Guidance’ item ‘Prescribing in palliative care'. Adpated from JFC (2021)

| Subject | Menu term |

|---|---|

| Equivalent doses of opioid analgesics | Pain management with opioids |

| Equivalent 24-hour doses of buprenorphine patches and oral morphine | Pain management with opioids |

| Equivalent 24-hour doses of 72-hour fentanyl patches and oral morphine | Pain management with opioids |

| Equivalent doses of morphine sulfate and diamorphine hydrochloride given over 24 hours | Continuous subcutaneous infusions |

Conclusion

The BNF app can help prescribers work in partnership with patients to use medicines safely. It provides fast, convenient access to validated, current information about medicines. However, it may not always include all the information needed, and knowledge is only one element of the competencies necessary to be a safe, effective prescriber.

Key points

- The British National Formulary (BNF) app provides prescribers with fast, convenient access to validated, current information.

- Digital BNF publications are preferable for prescribers, to assure clinical currency and reduce medicolegal risk.

- Developing the skills to efficiently navigate the BNF app enables prescribers to harness its wealth of information to support safe practice.

- BNF publications may need to be supplemented by other sources of information.

CPD reflective questions

- How will you use the British National Formulary App to ensure that the medication you prescribe is compatible with any other medication the person is taking?

- Which methods will you use to communicate the risk of side effects?

- What other resources do you need to supplement BNF content in your current practice?