The biggest issue faced within teaching inhaler technique is the continued morbidity and mortality for those using inhalers incorrectly and the contribution this makes to the increased use of healthcare resources. This is partly due to inadequate teaching of the correct inhaler usage and promotion of adherence (Price at al, 2017; Al-Jahdali et al, 2013). Another issue healthcare professionals face is the complexity of the number of devices available to prescribe and teach patients. It is estimated that there are over 20 devices with around 116 combinations of drug, device and dose, and this could be as many as 130 if the different pack sizes and refills available are included. Inhalers come in a range of colours and differ in their attributes such as dose counters, ease of use, internal resistance, handling and loading, making it challenging to stay abreast of all the devices.

Keep it simple

Medications

Despite numerous devices, there are relatively few classes of medication. There are beta agonists, both short- and long-acting, muscarinic antagonists; again short- and long-acting, and inhaledcorticosteroids. These classes of medication may be in the inhaler device as a single agent, a combination and now as triple therapy. There are numerous guidelines to help choose the right treatment (British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2019; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2018; Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease, 2019; Global Initiative for Asthma, 2019).

Type of inhaler

In terms of devices, there are only three types of inhaler available. These are the pressurised metered dose inhalers (pMDI), dry powder inhalers (DPI) and the soft mist inhaler (SMI).

Whilst there are variations in the devices, what is important is the inspiratory effort needed to get the medication to where it is required and the internal resistance of the inhaler. pMDIs are not breath actuated and will also require coordination of inspiration with activation of the device, although a spacer device can overcome the coordination problem for some people. All inhalers require these basic steps:

- Prepare the inhaler device

- Prepare (or load) dose

- Breathe out (not into inhaler)

- Slightly tilt the chin and place the lips around the mouthpiece creating a seal

- Breathe in:

- – MDI: Slow and Steady

- – SMI: Slow and Steady

- – DPI: Quick and Deep

- Remove inhaler from mouth and hold breath for up to 10 seconds or as long as is comfortable

- Repeat as directed (UK Inhaler Group (UKIG), 2019).

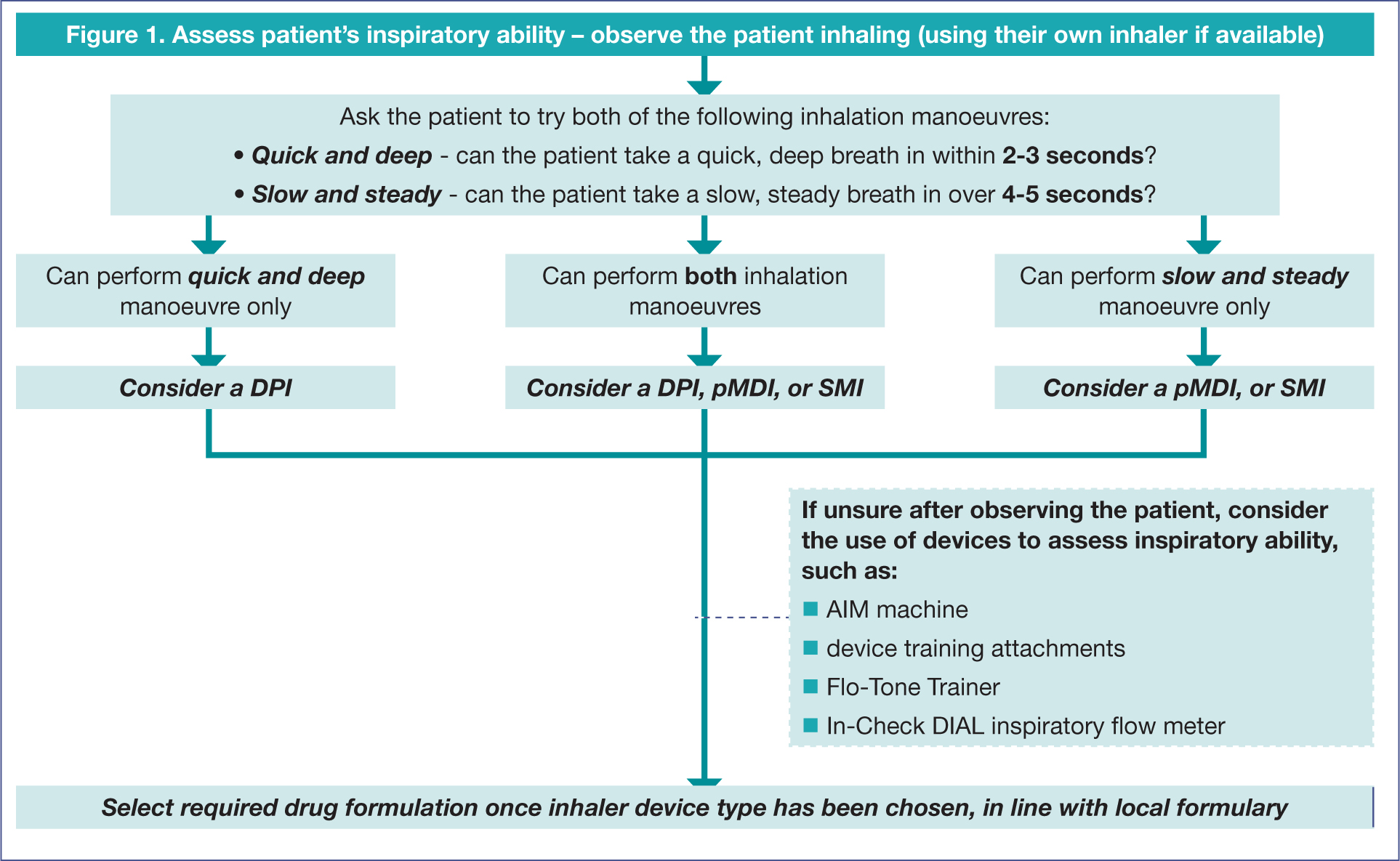

In addition, knowing the required inspiratory flow rate is important. For the pMDI and the SMI, the flow rate must be slow and inhaled steadily, and for the DPIs, quick and inhaled deeply. If the language used with patients is standardised so that healthcare workers are all using the same terms, a consistent message can be given and heard. The following algorithm is a practical approach to assessing the persons' inspiratory flow, although there are numerous other devices that can help monitor this, such as the two-tone device, the flo-tone, in check device, AIMS machine and whistles (Figure 1).

Getting the right inhaler device for people, either children or adults, is not always easy (Scullion, 2017a). It depends on many factors, including the person's age, manual dexterity, cognitive impairment, ease of use, inspiratory flow rate, licensing options, medication required and personal preference, amongst others (Scullion, 2017b). Many healthcare professionals still do not review inhaler technique and even when they do, they are not always aware of the correct technique for the device they either prescribe or review (Melani et al, 2011; Drugs and Therapeutics Bulletin, 2012). This is reinforced by a systematic review of 144 studies over a period of 40 years, which found that there had not been any improvements in adherence to inhalers or healthcare workers' ability to teach the correct technique, so it has to be about more than the inhaler device (Sanchis et al, 2016).

Dekhuijzen and colleagues (2013) suggest the 3W-H approach as a practical approach for prescribing inhalers considering the following four simple questions:

- Who: Patient characteristics, considering the disease, the severity, and fluctuations in airflow obstruction

- What: The medication required

- Where: Where in the lungs the medication should reach

- How: The best device for the individual patient. If healthcare workers ask these four simple questions, then teaching techniques can be better targeted around the most effective and efficient personalised prescription.

Teaching techniques

Although there are many learning theories, Visual Aural Reading Kinesthetic (VARK) learning styles are a simple way to think about how people see and respond to the world (Fleming and Mills, 1992a). The V stands for visual (spatial), where the preferred learning style is the use of pictures, images, and spatial understanding, seeing with the mind's eye. The A is aural (auditory-musical), with a preference for using sound and music. The R is reading (linguistic), with a preference for using words, both in speech and writing. Finally, the K is kinaesthetic (physical or feeling) preferring the use of the body, hands and sense of touch (Fleming and Mills, 1992b).

Healthcare workers can consider teaching inhaler techniques utilising VARK learning styles.

Visual

When checking inhaler technique, healthcare workers need to appeal to the visual senses. This involves showing and demonstrating the inhaler device that is being recommended. To appeal to the visual senses, practitioners might want to ask questions such as ‘could you see what life would be like if you controlled your asthma?’, ‘could you see that this would help your symptoms?’ or ‘can you see yourself using this device?’.

Aural

This involves what the patient hears, clear instructions, standardising the language used, such as using slow and steady for the pMDI and SMI, and quick and deep for the DPI, and using a common approach to all inhaler instructions, such as the seven steps approach to inhalers (UKIG, 2019). In conversation, healthcare workers might want to use questions such as ‘does this sound like something you could do?’ or ‘have you heard anything about using inhalers that bothers you?’.

Verbal

Verbal will involve the words practitioners use and the written instructions that can be supplied to supplement our teaching. There is a need to be clear and concise in our instructions, using standardised language similar to our aural approach and perhaps questions such as ‘have I read you correctly in your concerns about asthma?’ and ‘is this written plan what we agreed on?’.

Kinaesthetic

This will involve letting people handle and practice on devices and also using questions such as ‘what would it feel like to control your asthma?’ and ‘does this device feel right to you?’.

By adapting teaching styles to appeal to patients' preferred learning style, both understanding and adherence could be improved.

Ideas, concerns and expectations

The belief systems or patients' attributions of their illness are the basis of their health-seeking behaviour (Fleming and Mills, 1992a). If these beliefs can be simplified into ideas, concerns and expectations, this will allow healthcare teams to understand patients' motivations. This understanding can be used to improve satisfaction and adherence with medical advice. To truly understand patients, their ideas about their asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) need to be addressed, including any concerns they have, especially over the medications prescribed, such as side effects or whether taking medication daily makes it less effective. Finally, expectations over their treatment and its effects should be discussed. If patients' ideas, concerns and expectations are not taken into account, healthcare workers could fail to understand a person's health behaviour.

Ideas that are beliefs could be addressed by questions, such as ‘tell me what you think is aggravating your condition?’ or ‘do you have any ideas about treatment yourself?’. Questions useful for addressing concerns can be framed into statements, such as ‘is there anything in particular or that you are concerned about?’ or ‘what concerns you most about what we have discussed?’. Managing the patient's expectations can involve questions such as ‘how can I help you with this?’ or ‘what do you think would be the best plan?’

It is everybody's job

The UKIG is a coalition of not-for-profit organisations and professional societies who share a common interest in promoting the correct use of inhaled therapies. They aim to improve the outcomes of patients with respiratory conditions, and for the NHS to derive maximum value from inhaled treatment.

In 2016, they published inhaler standards, which have now been updated (UKIG, 2019). If healthcare workers want patients to take their inhalers seriously, then they must make sure they take them seriously themselves. It is not enough to say it is just an inhaler, professionals need to talk about inhalers as the medications for asthma and COPD, and not just as inhalers. The UKIG supports the concept that inhalers are an essential medication in asthma and COPD symptom control, and for preventing asthma deaths. A third of asthma deaths in the UK can be directly linked to non-adherence, demonstrating the importance of proper care (National Review of Asthma Deaths, 2014).

If patients do not bring their inhalers with them to an appointment, practitioners may need to discuss why. If this is because they do not consider them as medicines, healthcare workers should explore this. This gives insight into areas professionals need to address with the patient, making sure they know their inhaler is important and is the medication to deal with their condition.

If healthcare workers do not change their interactions with patients, they are potentially contributing to the unnecessary morbidity and mortality for asthma and COPD and wasting valuable healthcare resources. Consultations with patients need to be examined to make them effective and efficient. When it comes to teaching about inhalers, workers must know it, show it, check it and review it at every consultation, utilising the understanding of different learning styles and addressing patients' ideas, concerns and expectations. The perception of inhalers as ‘just an inhaler’ needs to be changed, it is the medication that is required for symptom control and prevention. With no change in adherence or outcomes over the years, healthcare professionals need a new approach to be effective in consultations when educating patients about inhalers.

Key Points

- Inhalers are everybody's business

- Mortality and morbidity will not improve unless inhalers are taken seriously

- Simple teaching inhaler use will not work without addressing patients ideas concerns and expectations

- Healthcare workers approach needs to be adapted to meet the patients learning styles

- Keeping it simple helps.

CPD reflective questions

- Having read through the article what will you do differently when teaching patients about inhalers?

- Thinking through your last five consultations, what were the main ideas patients had about inhalers?

- Can you think what common misconceptions patients have about their inhalers?

- Reflecting on patients you have seen what are patients main concerns around inhalers ? Does this vary between asthma and COPD patients?

- What is your favourite learning style and how can you adapt this to meet your patients individual learning styles?