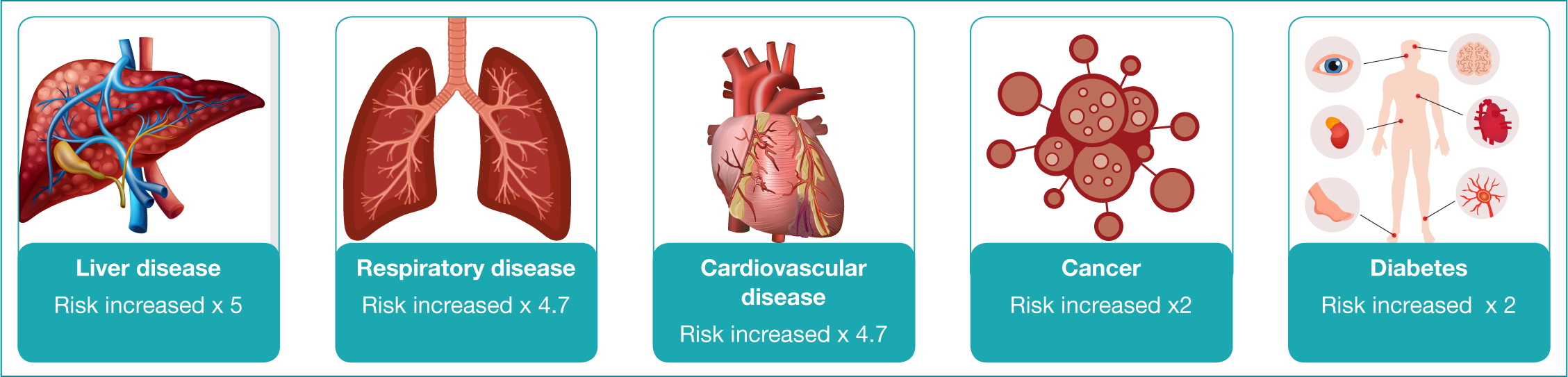

Although mental and physical health problems are treated separately, mind and body are, in fact, inextricably linked. People with mental health problems are more likely to have physical health problems than the general population (Public Health England (PHE), 2018). People with what is referred to as ‘severe mental illness’ (SMI) – those with psychological problems, such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder that severely impair their functional ability – are not only more likely to have physical health problems, but also experience greater difficulty in managing these problems (PHE, 2018). Figure 1 outlines how people with mental health issues are at increased risk of physical illness.

Nurses trained to care for people with mental health problems may struggle to recognise and meet physical health needs, and some NHS Trusts providing mental health services have appointed specialist and consultant nurses to work with staff to improve physical health in mental health settings (Department of Health (DH), 2016; Nazarko, 2017).

Nationally, Diabetes Mellitus (DM) affects 7.4% of the population, and 15% of those with SMI (PHE, 2018). People with DM occupy 14-30% of hospital beds nationally, and have a 74% increased risk of acute admission and a 25% increased risk of re-admission (Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2015; Becker and Hux, 2010; Chwastiak et al, 2014).

This article illustrates how a nurse specialist in diabetes working in an acute NHS Trust and a nurse consultant working in mental health inpatient wards can work together to provide holistic care that reduces the risk of vulnerable patients having to attend Accident and Emergency (A&E) departments and acute hospital admission, whilst experiencing acute mental health problems.

Overview and assessment

This article outlines how physical and mental health issues impact on the health of an individual. ‘Raminder Kaur’ is a 45-year old lady who has depression and type two diabetes mellitus (DMT2). Pseudonyms and changes to patient details have been made to protect patient confidentiality (Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC), 2019). Patient dignity, privacy and autonomy have been respected throughout consultation, examination and treatment planning (Royal College of Nursing (RCN), 2008; NMC, 2019).

Mrs Kaur was referred to a consultant nurse by ward staff as her blood glucose level was 30 mmol/L. A blood glucose level of 30 mmol per-litre would, in the past, have led to an automatic referral to A&E. However, due to the nurse specialist in diabetes working in partnership with the nurse consultant in mental health, support for Mrs Kaur could be provided within the unit.

Consultation model

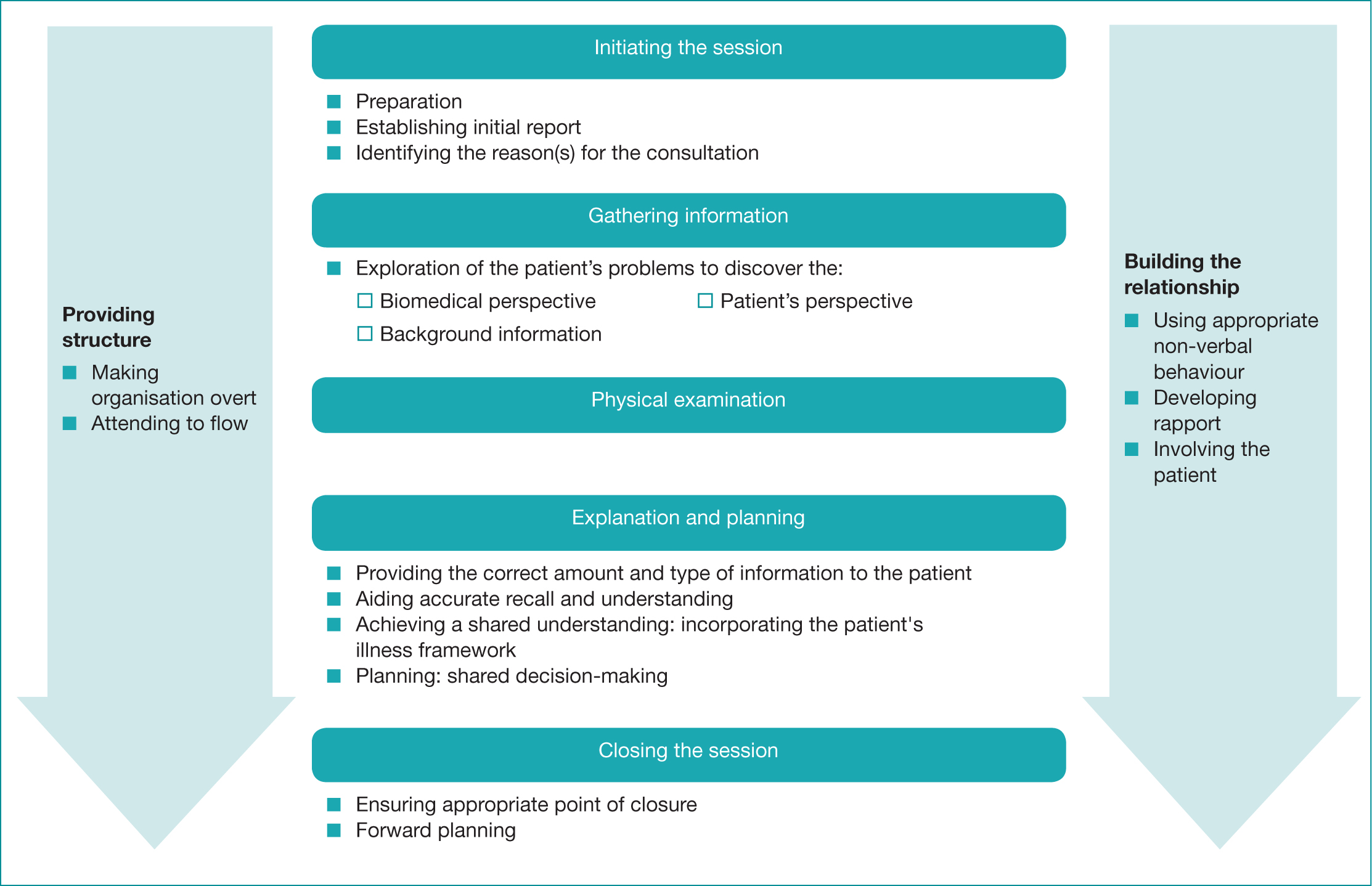

The Calgary-Cambridge model is used as a framework for assessing, diagnosing and treating patients.(Kurtz and Silverman, 1996; Kurtz et al, 1998). This model aims to enable the practitioner to recognise the patient’s understanding, beliefs and motivation and to use interventions that engage patients in their care (Dowell et al, 2002: Kurtz et al, 2003; Kurtz, 2009). Figure 2 outlines the refined Calgary-Cambridge model.

Introduction and initiating session

Mrs Kaur is a 45-year old lady who was admitted to an acute psychiatric ward due to depression. She is an informal patient and is able to come and go from the ward as she wishes. She is expected to be on the ward for medication and reviews, and to sleep on the ward. The aim of the admission was to treat her depression, which had not responded to treatment at home. Mrs Kaur was referred to physical health services because of her high blood glucose level.

Gathering information

Taking a history enables a healthcare professional to obtain subjective data relating to the presenting problem and other health issues (Bickley and Sziagyl, 2013). Table 1 provides details of Mrs Kaur’s history.

Table 1: Details of patient history

| Presenting problem(s)/complaint(s) |

|

| Other problems or issues of note |

|

| Past medical history and long term conditions |

|

| Family history |

|

| Social history |

|

| Medication |

|

| OTC/Herbal medication | None |

| Alcohol and smoking history | Mrs Kaur has never smoked and does not drink alcohol |

| Allergies | None known |

| Immunisations | Patient unsure |

Mrs Kaur explained that she had been diagnosed with diabetes about 10 years ago. At first she felt better with the treatment, but then the diabetes got worse and she had more medicine to take. She said she hadn’t been feeling well ‘all summer long’ but didn’t know if it was because she was depressed. She said that she felt very tired, was very thirsty and was passing lots of urine.

Physical examination

Physical examination aims to provide objective data that complements the history (Bickley and Szilagyl, 2013). Epstein and colleagues (2008) state that over 80% of diagnoses are made solely on the basis of history. This was true with Mrs Kaur.

Mrs Kaur was clean, tidy, warm and well perfused. She was able to walk long distances unaided and appeared a little unsteady. Her National Early Warning Score (NEWS) was 1, indicating low risk (Royal College of Physicians, 2017). She presented with the following upon assessment:

- Pulse: 72 bpm

- Temperature: 36.2°C

- Respiration rate: 18

- O2 saturation: 98%

- Blood pressure: 108/70 mmhg CGS15/15

- Weight: 52 kg

- BMI: 2.1

- Blood glucose: 30 mmols/litre urine dipstick – shows glucose +++ and is negative for ketones

- Chest is clear

- Pedal pulses: palpable

- Cranial nerves: intact

- Central nervous system: unremarkable

- Peripheral nerves were checked using 128 Hz tuning fork: normal vibratory sensation sense bilaterally

- The abdomen was normal

- The aortic, renal, iliac and femoral arteries auscultated, no bruits were noted

- Bowel sounds were heard in all four quadrants, no abnormalities noted

- Muscular skeletal system was normal

- Integumentary system and lymphatic normal with no evidence of any fungal infection.

The examination identified two red flags, these were:

- Poor diabetic control

- Risk of dehydration.

Diagnosis

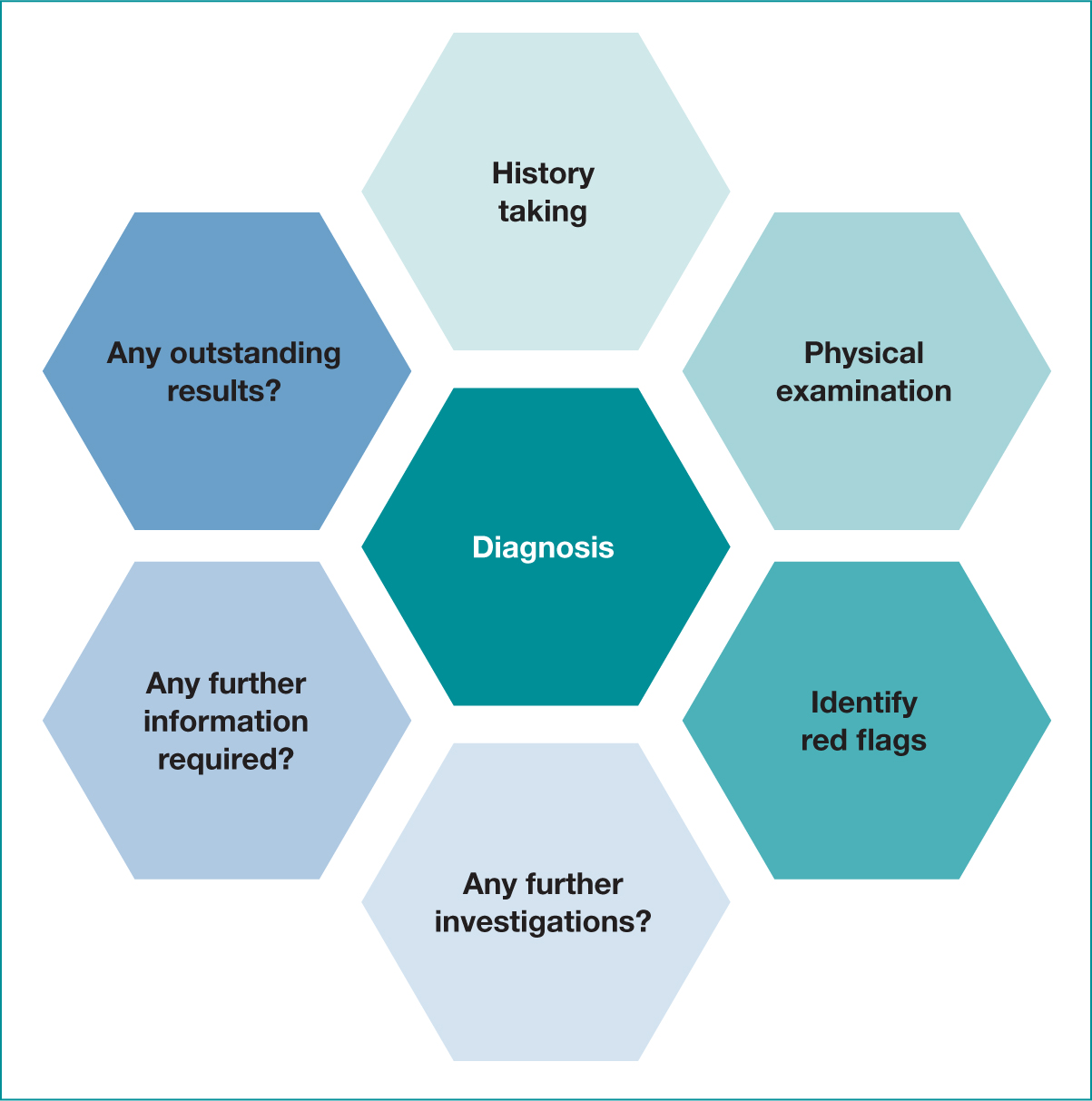

The Calgary-Cambridge model refers to this process as ‘explanation and planning’. This involves putting together information obtained from the history, physical examination and the results of any tests to formulate a diagnosis. Figure 3 outlines the process.

Management and investigation

There were two clinical priorities, to treat the elevated blood glucose and to ensure Mrs Kaur remained well-hydrated.

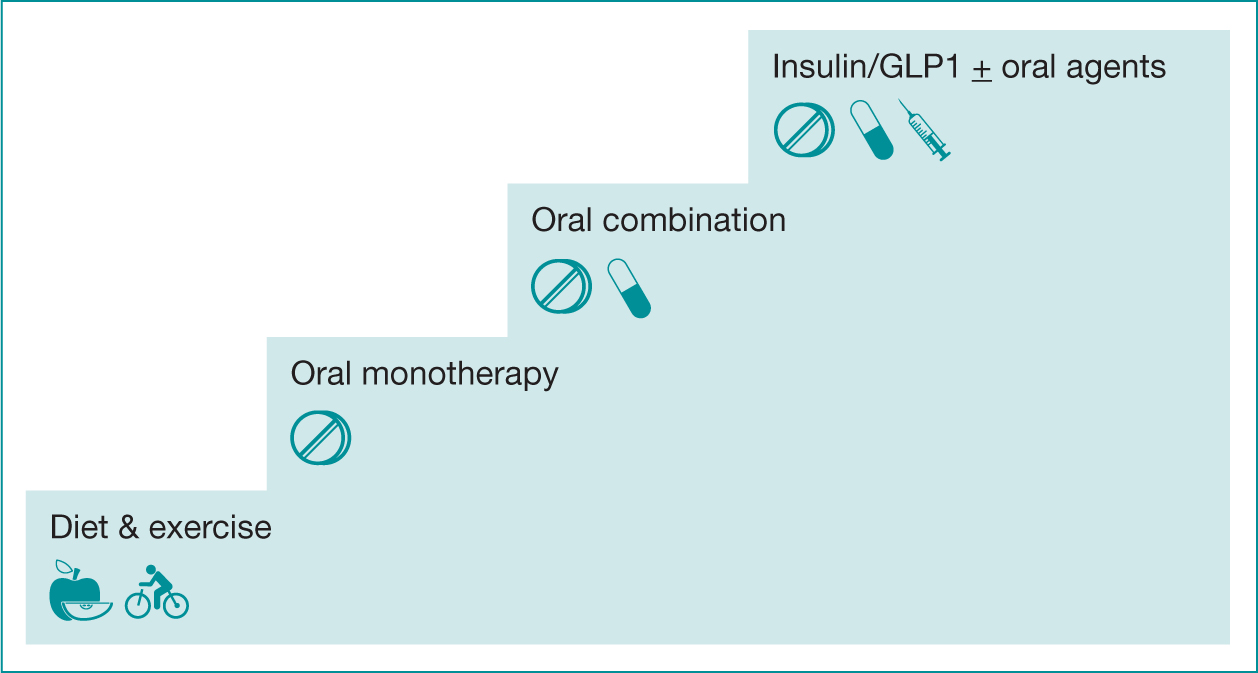

The evidence base recommends that clinicians adopt an individualised approach to diabetes care that is tailored to needs and circumstances, personal preferences, risks and ability to benefit from interventions (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2019). Mrs Kaur should follow dietary advice, and have her blood pressure monitored and maintained at 140/80 mmhg in the absence of renal, ophthalmic or eye damage. HBA1c target should be 48% and should be checked every 3-6 months until stable and then every six months. Around 60% of people with DMT2 achieve an HB1Ac of below 59 (DH, 2010). Figure 4 outlines the recommended stepwise treatment of DMT2 (NICE, 2019).

Explanation and planning

It was explained to Mrs Kaur that her pancreas wasn’t able to produce much insulin and that she would need to have insulin injections. She agreed to this. Gliclazide 40 mg twice daily was discontinued as Mrs Kaur had reduced insulin secretion and an increase in gliclazide would be ineffective and encourage weight gain (British National Formulary (BNF), 2020). A dose of novorapid (8 units) was immediately given. The aim was to reduce blood glucose to between 7-10 mmol/l in order to avoid a hyperglycaemic hyperosmotic state in relation to high blood glucose and dehydration. This used 1 unit to reduce blood glucose by 3 mmol, thus avoiding hypoglycaemia (JBDS, 2019). She was commenced on insulin glargine (16 units once daily) and novorapid PRN (6-10 units up to four times a day). If the patient’s blood sugar is 30, then give 10 units. However, if their blood sugar is greater than 12, then 6 units should be given. The target glucose was 6-12, and if blood glucose is persistently greater than 12, glargine should be increased by 2-4 units daily to achieve the target range. The use of insulin was to reduce osmotic symptoms in a safe and effective manner, and the aim of increasing the dose incrementally to achieve target blood glucose was recommended by NICE (2016). She was encouraged to drink plenty of unsweetened fluid. The patient’s ability to understand and address these psychosocial and environmental factors contribute to the improvement of her quality of life.

It was initially thought that Mrs Kaur’s English and her understanding of her diabetes were better than they actually were. She appeared to understand her diabetes and the importance of a diet low in sugar. However, this was not the case. Table 2 summarises Mrs Kaur’s difficulties and how these were addressed to improve outcomes and quality of life.

Table 2. Addressing issues relating to treatment and wellbeing

| Problem | Reasons | How this was addressed |

|---|---|---|

| Not eating a healthy diet low in sugar |

|

|

| Perceiving that in order to control diabetes she had to cut down on her food and only eat half of normal portions |

|

|

| Attending follow-up appointments |

|

|

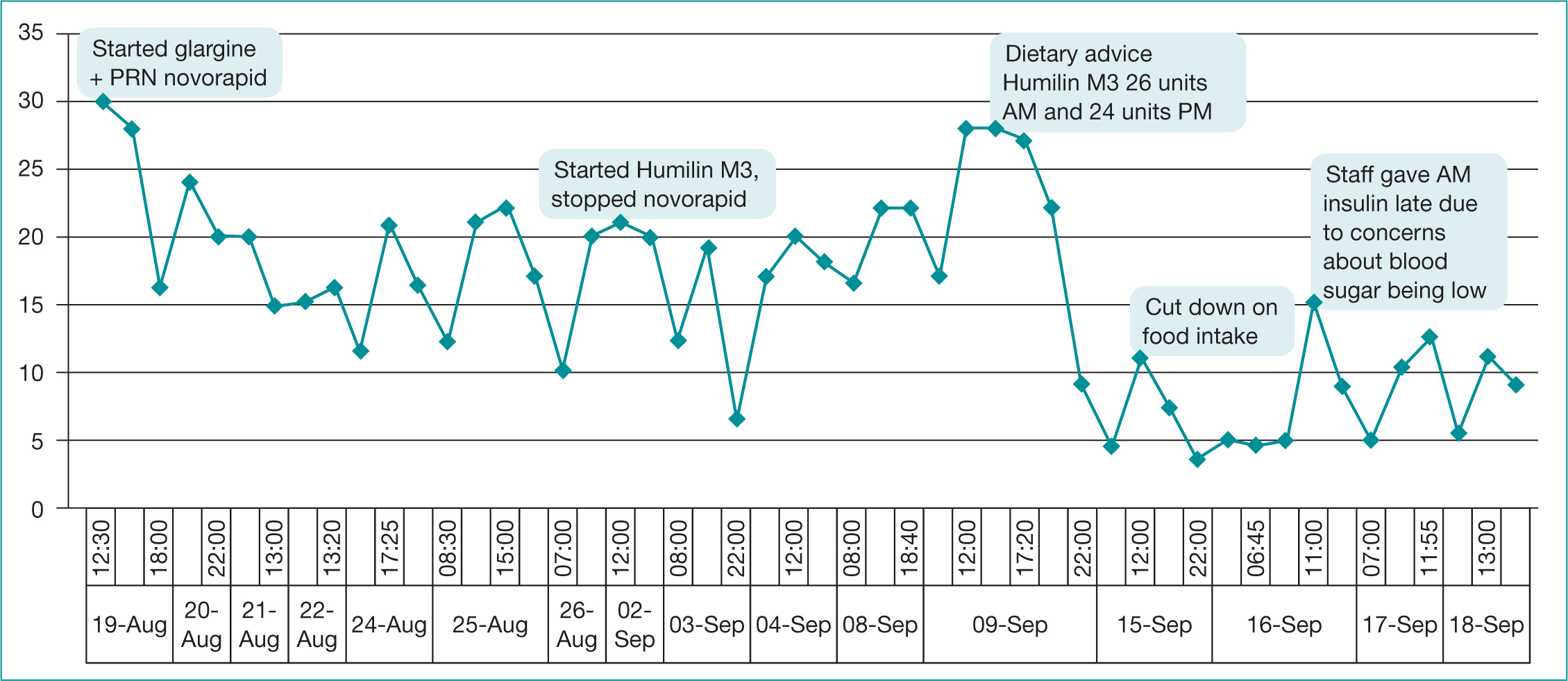

Patient progress

Mrs Kaur commenced on 20 units of glargine, a long-acting insulin, on 19 August and this was increased incrementally to stabilise blood glucose within the target range of 6-12 mmols. Mrs Kaur drank sufficient sugar-free fluids throughout her admission. By the 26 August, Mrs Kaur was on 36 units of glargine daily. Her blood glucose remained out of range and she was still requiring pro re nata novorapid insulin. Mrs Kaur was allowed to go home on leave and to stay with her family. She returned to the ward on 2 September where she was switched to humilin M3, 20 units twice daily. This was titrated upwards in an effort to improve blood glucose. Mrs Kaur had found managing multiple medications overwhelming and it was thought to be challenging for her to manage glargine and novorapid, as this would require her to increase the dose independently based on her current blood glucose. As such, her humulin M3 was changed to twice daily, as this was less burdensome and simpler for her to manage. If she was unable to manage independently she would only require assistance twice a day.

On 9 September, Mrs Kaur was on 30 units of humilin M3 AM and 28 units PM, and her blood glucose was not well-controlled. NICE (2019) guidance emphasises the importance of providing individualised and ongoing nutritional advice that is sensitive to the person’s needs, culture and beliefs. This advice should be integrated within the diabetes management plan.

A multidisciplinary team was put together to explore the reasons for her lack of improvement, and one member of staff reported that Mrs Kaur had started to go out and was visiting a nearby Mark’s and Spencer’s (M&S). The staff member had noted Mrs Kaur was buying yum yums (twisted, fried, sugar coated doughnut sticks) and Percy Pigs. An interpreter was found and asked Mrs Kaur how often she visited M&S and she told us she’d been visiting every day as there wasn’t much to do on the ward. She said everyone spoke in English, the television programmes were in English and there was no one she could talk to. She explained that going to M&S and buying yum yums and Percy Pigs was the highlight of her day and that sometimes she had two packets of yum yums or two packs of Percy Pigs, one in the morning and one in the afternoon.

Time was subsequently spent explaining about diabetes and diet. A leaflet was found on type two diabetes in Punjabi (Diabetes UK, 2017) (see further resources) and it was arranged for a Punjabi-speaking dietician to visit her. Blood glucose control improved significantly, however, she began to have hypoglycaemic episodes. Ward staff reported that Mrs Kaur was no longer buying sweet foods and was only eating about half of her meals. Thus, the interpreter visited again with her care team, discussing Mrs Kaur’s diabetes. She said that she now understood that diabetes was a serious condition and she was trying to limit her food intake to improve her diabetes. She said that the leaflets had stressed the importance of weight management. The team explained that her weight was normal and it wasn’t necessary for her to lose weight. Mrs Kaur’s evening insulin was reduced to 24 units in the evening. Her blood glucose then settled within the required range of 6-12 mols. Figure 4 illustrates Mrs Kaur’s blood glucose control over the period of intervention.

Supporting staff

Normally, when an inpatient developed high blood glucose, the patient would have attended A&E and might have been admitted in order to stabilise blood glucose levels. Medical and nursing staff were a little anxious about caring for Mrs Kaur on the mental health unit, however, they felt that it would be best if she could remain on the ward as her mental health was improving and they felt a hospital admission could have been detrimental. On one occasion, staff omitted an evening dose of metformin and on another occasion Humilin M3 was not given until 11 AM because of concerns about blood glucose levels. Additional educational sessions with staff were carried out regarding normal blood glucose levels and the importance of not omitting insulin was explained (JBDS, 2019). The ward was visited frequently to titrate insulin and educate staff. At a ward meeting, staff stated that they felt proud that they had managed to support Mrs Kaur and avoid A&E attendance and an admission to an acute ward. They said that they felt more confident about caring for people with diabetes who required insulin.

Diabetes and depression

Depression is twice as common in people with diabetes than it is in the general population. A report of an international meeting of physicians, specialising in diabetes and mental health, stated that although diabetes may contribute to depression, there are thought to be biological, cultural and behavioural mechanisms that contribute to people with diabetes developing depression. Our understanding of these is not complete and further research is required. The report stated that ‘training programs are needed to create a cross-disciplinary workforce that can work in different models of care for comorbid conditions’ (Holt et al, 2014).

A Cochrane review to determine the effect of psychological therapies and antidepressants on depression, blood sugar, adherence to diabetic treatment, diabetes complications, mortality and quality of life, found that antidepressant drugs have a positive effect on depression and on blood glucose control. Further research is required to determine if there is any reduction in diabetes complications (Baumeister et al, 2012).

Mrs Kaur’s depression made her feel that she had no prospect of having a happy and fulfilled life. As a result of her depression, she had stopped attending her diabetes reviews and her worsening diabetes was undetected until she was admitted to the ward. As Mrs Kaur’s diabetic control improved, she also felt better mentally and her physical and mental health were clearly linked. Mrs Kaur’s consultant psychiatrist spoke with Mrs Kaur, her husband and her sister. They made plans to help Mrs Kaur become more involved in the Punjabi-speaking community to help her become less isolated and vulnerable to depression.

The benefits of joint working

It took a long time to stabilise Mrs Kaur’s blood glucose and our input enabled her to remain in the mental health unit, receiving treatment for her depression and her diabetes. Her diabetic control and her mental health seemed linked and as her diabetes control improved, her mental health also improved. She was discharged home under the care of the community mental health and community diabetes specialist nurses and remains well.

Conclusion

NICE (2019) guidance recognises the importance of educating and enabling people with diabetes to manage their condition. Mrs Kaur’s limited understanding of her diabetes was compounded by her limited English and her depression made it difficult for her to understand the severity of her diabetes, to engage with clinicians, to participate in reviews and to manage diabetes well. There are unique challenges in enabling people such as Mrs Kaur to manage diabetes well. It is important to understand the interaction between mental health, psychological, social, environmental and physical factors and to use that knowledge to develop a plan of care and treatment that supports and empowers the individual.

Clinicians need to do their utmost to understand the patient’s perspective and to work with them to minimise risk of harm and optimise health and wellbeing. The importance of checking and understanding language skills thoroughly was highlighted during this study (Kar, 2018).

Many people with mental health issues are at increased risk of illness (NHS Digital, 2016; Hayes et al, 2017; John et al, 2018) and the appointment of nurse consultants within mental health settings is a positive step in improving registered patients’ physical health, however, there is much more to be done. Nurse specialists and nurse consultants working in acute settings can work with their colleagues in mental health to reduce the barriers to holistic care and reduce accident and emergency attendances and inpatient admissions. This will ultimately not only improve care but also reduce costs. The barriers that need to be overcome in order to do this are cultural and economic. This article demonstrates that the value of cross-disciplinary working and how it should be valued and supported in future practice.

Further resources

- Diabetes the basics (Diabetes UK, 2017) is available in a number of different languages, including Punjabi.

- Visit: https://www.diabetes.org.uk/diabetes-the-basics/information-in-different-languages

Key Points

- The incidence of depression in people with diabetes is double the national average

- Depression can impact on a patient’s ability to manage diabetes

- It is important that clinicians are aware of the interaction between mental and physical health

- Staff working across acute and mental health can provide care that is seamless to the patient at point of delivery and provides improved outcomes

- Joint working can also be cost-effective as it can reduce accident and emergency attendances and hospital admission

CPD reflective questions

- What particular problems might a person who has limited English face in managing his or her diabetes?

- What can the practitioner to do help the person to overcome communication difficulties?

- Why was it necessary to stop gliclazide and commence insulin?

- Will you make any changes to your practice as a result of reading this article?