The incidence of prostate cancer (PrC) is rising and the number of patients is likely to double by 2020 in India as per cancer projection data (Jain et al, 2014); Updated figures or predictions of the year 2020 have not been reported yet. PrC has progression free- and overall-survival in years and necessitates careful management to ensure good quality of life for patients. Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), either medical or surgical castration, is the primary treatment modality, in combination with radiotherapy for locally aggressive PrC (National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), 2019). Medical castration includes luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone-agonist (LHRH-A) (leuprolide, or triptorelin), either alone or with first-generation antiandrogen medicines (nilutamide, bicalutamide) to achieve complete androgen blockade (CAB), while surgical castration is done by bilateral orchiectomy (Akaza et al, 2009; NCCN, 2019). Radical prostatectomy is indicated in early stage PrC, with absence of lymph node involvement and metastasis (NCCN, 2019). Multiple medications are available for castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), such as second-generation antiandrogen (apalutamide, enzalutamide), fosfestrol, abiraterone plus prednisolone, ketoconazole plus hydrocortisone, mitoxantrone, docetaxel or cabazitaxel. Their uses depend upon disease burden, life expectancy, comorbidities and socioeconomic status of the patient (NCCN, 2019). Recently, landmark clinical trials such as CHAARTED (Sweeney, 2015), STAMPEDE (James et al, 2017) and LATITUDE (Fizazi et al, 2017) have provided critical evidence to guide treatment decisions for CRPC. While CHAARTED and STAMPEDE had substantiated early use of chemotherapy with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) in patients with extensive metastases, LATITUDE had presented compelling evidence to initiate abiraterone in metastatic hormone sensitive PrC. In essence, a multimodal approach should be taken for management of PrC because of heterogeneity.

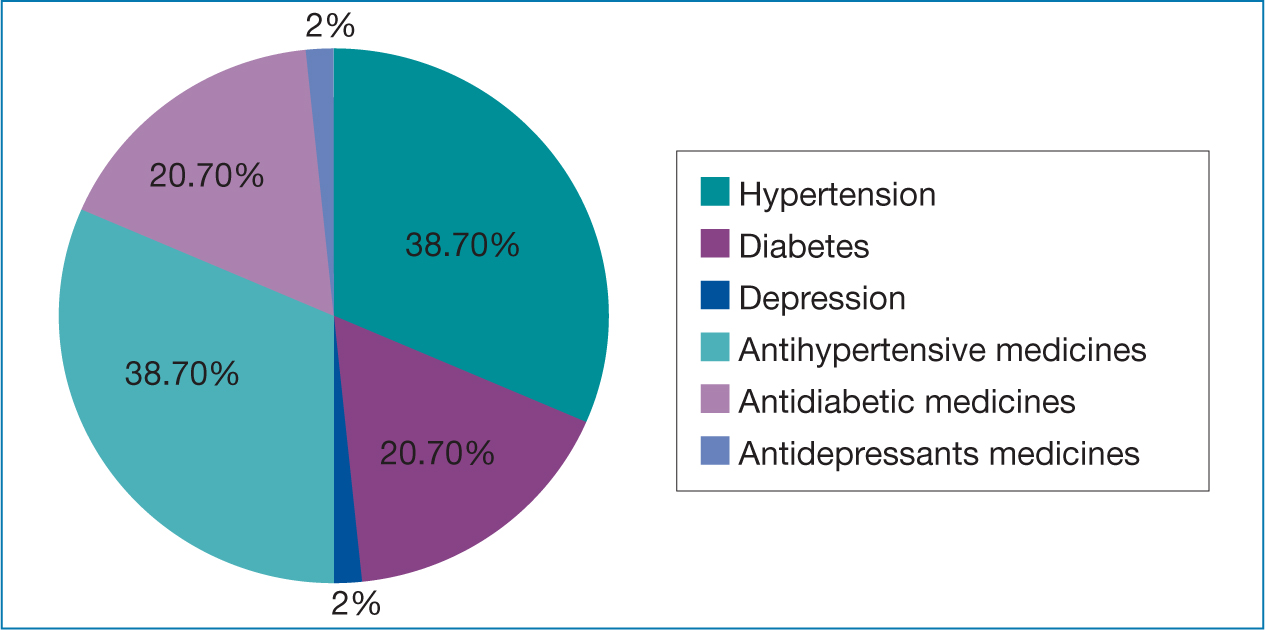

Depression, a common comorbidity, is seen in approximately 15–25% in PrC, with treatment subjective to severity of symptoms (Smith, 2015). Hypertension has a high co-prevalence with PrC, because there are similar risk factors (de Souza et al, 2015; Liang et al, 2016). On the other hand, diabetes does not show increased predilection in PrC, compared to other cancers (Lutz et al, 2018).

Few studies have captured real-world prescription data in PrC to analyse the rationality of prescribed medicines using core indicators and the drug utilisation methodology (DUM) of the World Health Organization (WHO). These include adherence to standard guidelines, such as NCCN, for cancers. Core indicators include the essential medicines list (National List of Essential Medicines (NLEM), 2015), polypharmacy, injectables and antibiotics. The objective of this study was to capture real-world prescription data for PrC and common comorbidities, using core indicators and the DUM.

Methods

This cross-sectional study lasted one year and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki regarding human experiments. The institutional ethics committee approved this study (IECPG-559/20.12.2017). All patients who were included in the study signed an informed consent form. The diagnosis and management of patients were done as part of routine care in oncology and urology departments. A bone scan counts the number of bone metastatic sites and is routinely used to measure tumour aggressiveness. Tumour aggressiveness and castration response guide PrC management. Therefore, instead of using tumour, node, metastasis (TNM) staging, patients were grouped based on:

- Bone metastasis: B0 (absent) and B1 (present)

- Castration response: CSPC (castration-sensitive prostate cancer) and CRPC (castration-resistant prostate cancer).

B0 and B1 were newly diagnosed patients for whom treatment was started <1 week ago. Patients' history and medical records provided medication usage data. Patients were identified as having hypertension, diabetes and/or depression from retrospective data in their records. Prescriptions were evaluated for antidepressant, antihypertensive, antidiabetic and anticancer medicines. Prescribed daily dose (PDD), defined daily dose (DDD), their ratio (PDD:DDD), percentages of patients on individual medicine and medicines from NLEM were calculated. Summary statistics was used to describe the data.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria were patients aged ≥18 years diagnosed with prostate cancer. Exclusion criteria were patients who did not provide signed informed consent for participation. Only biopsy proven cases were recruited in the study.

Results

A total of 150 patients fulfilled the eligibility criteria and were recruited for the study. Demographic and baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1 and comorbidities and medication usage (%) are depicted in Figure 1.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of prostate cancer patients (n=150)

| Parameter | B0 (n=30) | B1 (n=28) | CSPC (n=42) | CRPC (n=50) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years [mean (SD)] | 69.5 (6.18) | 63.2 (9.65) | 67.5 (8.69) | 65.7 (11.07) |

| Gleason score | ||||

| Median (range) | 7 (6–9) | 8 (7–10) | 8 (6–9) | 8 (7–10) |

| ≤6 | 11 | 0 | 6 | 1 |

| 7 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 11 |

| ≥8 | 9 | 21 | 27 | 38 |

| Tumour burden/number of metastatic sites* | ||||

| Regional lymph nodes | 4 | 16 | 22 | 32 |

| Bone | 0 | 28 | 11 | 48 |

| Non-regional lymph nodes | 0 | 9 | 9 | 24 |

| Viscera | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) ng/ml | ||||

| Median (range) | 21.42 (5.13–119.8) | 100 (34.01–216.7) | 0.35 (0.008–87.3) | 24.75 (1.19–551.2) |

| 0–4 | 3 | 1 | 35 | 5 |

| >4 | 27 | 26 | 7 | 40 |

Prescription pattern analysis

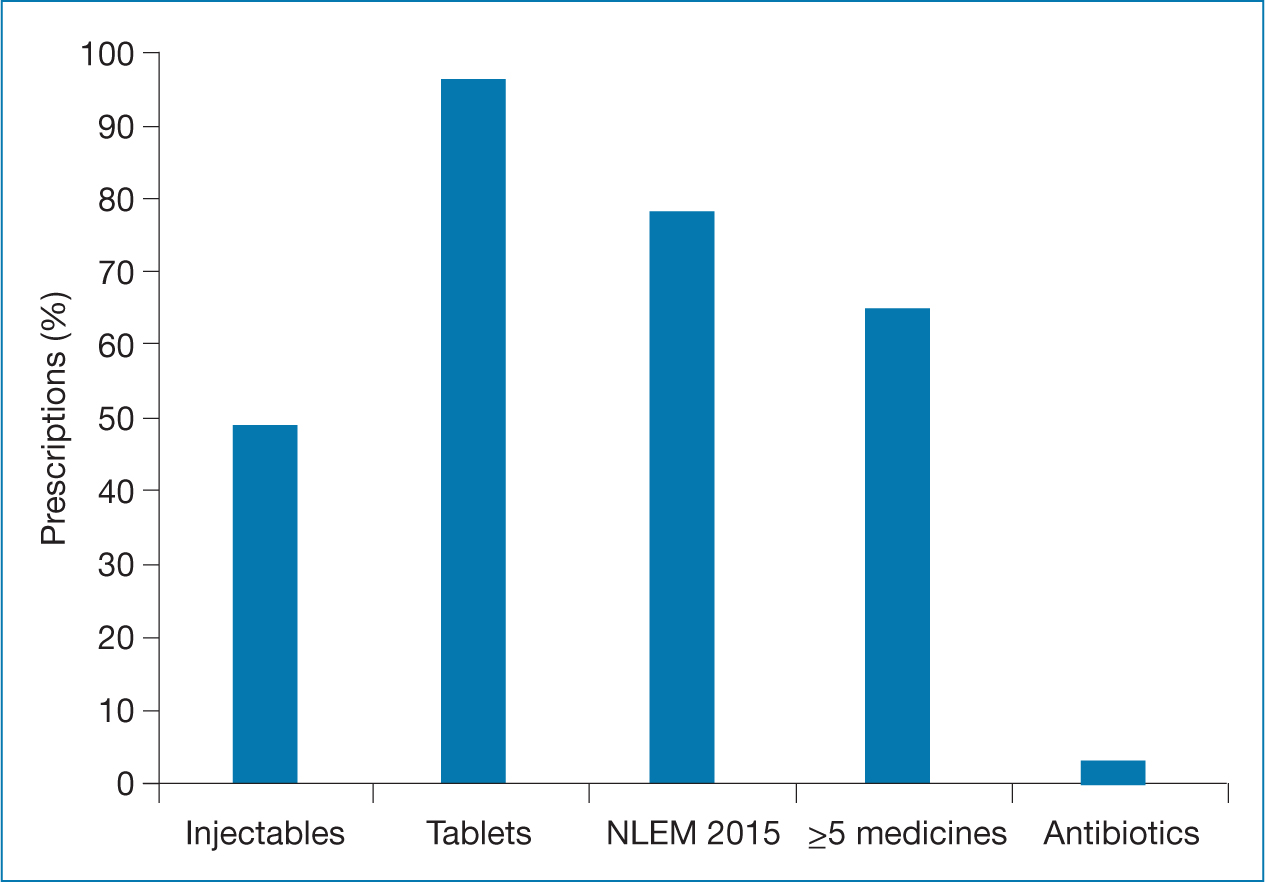

WHO core indicators are given in Figure 2. The average number of medicines per prescription was 5.7. PDD, PDD:DDD ratio and the number of DDDs were calculated for antidepressant, antidiabetic, antihypertensive and anticancer medicines (Tables 2, 3 and 4).

Table 2. Drug utilisation methodology for antidepressant, antihypertensive and antidiabetic medicines

| Anatomical therapeutic chemical | DDD (mg) | No. of DDDs | % of patients | PDD (mg) | PDD: DDD | NLEM 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antidepressant medicines (Tablet) | ||||||

| Paroxetine (N06AB05) | 20 | 1.25 | 33.3 | 25 | 1.25 | No |

| Escitalopram (N06AB10) | 10 | 1.5 | 66.7 | 30 | 0.75 | Yes |

| Antihypertensive medicines (Tablet) | ||||||

| Amlodipine (C08CA01) | 5 | 40 | 50 | 6.9 | 1.38 | Yes |

| Losartan (C09CA01) | 50 | 1 | 1.7 | 50 | 1 | Yes |

| Nebivolol (C07AB12) | 5 | 1 | 1.7 | 5 | 1 | No |

| Hydrochlorthiazide (C03AA03) | 25 | 4 | 10.3 | 17 | 0.7 | Yes |

| Metoprolol (C07AB02) | 0.15 | 1.17 | 8.6 | 35 | 0.23 | Yes |

| Enalapril (C09AA02) | 10 | 0.75 | 5.17 | 2.5 | 0.25 | Yes |

| Prazosin (C02CA01) | 5 | 1 | 1.7 | 5 | 1 | No |

| Indapamide (C03BA11) | 2.5 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 1.25 | 0.5 | No |

| Ramipril (C09AA05) | 2.5 | 7 | 8.6 | 3.5 | 1.4 | Yes |

| Atenolol (C07AB03) | 75 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 50 | 0.7 | Yes |

| Perindopril (C09AA04) | 4 | 1 | 1.7 | 4 | 1 | No |

| Antidiabetic medicines (Tablet) | ||||||

| Metformin (A10BA02) | 2 | 5.5 | 45.16 | 785.7 | 0.39 | Yes |

| Glibenclamide (A10BB01) | 10 | 2 | 6.45 | 10 | 1 | Yes |

| Sitagliptin (A10BH01) | 0.1 | 1 | 3.23 | 100 | 1 | No |

| Glimepiride (A10BB12) | 2 | 6 | 19.35 | 2 | 1 | Yes |

| Gliclazide (A10BB09) | 60 | 4.5 | 12.9 | 67.5 | 1.13 | No |

| Pioglitazone (A10BG03) | 30 | 0.5 | 3.23 | 15 | 0.5 | No |

| Vildagliptin (A10BH02) | 0.1 | 0.5 | 3.23 | 50 | 0.5 | No |

| Canagliflozin (A10BK02) | 0.2 | 0.5 | 3.23 | 100 | 0.5 | No |

| Glipizide (A10BB07) | 10 | 0.5 | 3.23 | 5 | 0.5 | No |

| Antibiotics (Tablet) | ||||||

| Ofloxacin (J01MA01) | 400 | 1 | 0.6 | 400 | 1 | Yes |

| Levofloxacin (J01MA12) | 500 | 1 | 0.6 | 500 | 1 | Yes |

| Nitrofurantoin (J01XE01) | 200 | 1 | 0.6 | 200 | 1 | Yes |

| Cefixime (J01DD08) | 400 | 1 | 0.6 | 400 | 1 | Yes |

| Amoxicillin and Clavulanic acid (J01CR02) | 625 | 1 | 0.6 | 625 | 1 | Yes |

Note: DDD-Defined daily dose, PDD-Prescribed daily dose, NLEM-National List of Essential Medicines

Table 3. ATC and DDD for anticancer medicines

| ATC code | DDD (mg) |

|---|---|

| Tab Bicalutamide (L02BB03) | 50 |

| Injection Leuprolide (L02AE02) | 5 once in 3 months |

| Injection Triptorelin (L02AE04) | 5 once in 3 months |

| Tab Fosfestrol (L02AA04) | 250 |

| Tab Abiraterone (L02BX03) | 1000 |

| Tab Enzalutamide (L02BB04) | 160 |

| Docetaxel (L01CD02) | Not available |

(ATC-Anatomical therapeutic chemical, DDD-Defined daily dose)

Table 4. Drug utilization methodology for anticancer medicines

| Group (n) | Medication | No. of DDDs | % of patients | PDD (mg) | PDD: DDD | NLEM 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B0 (30) | Bicalutamide | 25 | 80 | 50 | 1 | Yes |

| B1 (28) | Bicalutamide | 25 | 92.6 | 50 | 1 | Yes |

| Leuprolide | 18 | 15 | 22.5 | 4.5 | No | |

| Triptorelin | 4.5 | 7.5 | 11.25 | 2.25 | No | |

| CSPC (42) | Bicalutamide | 41 | 98 | 50 | 1 | Yes |

| Leuprolide | 36 | 19 | 22.5 | 4.5 | No | |

| Triptorelin | 36 | 38 | 11.25 | 2.25 | No | |

| CRPC (50) | Fosfestrol | 23 | 32 | 360 | 1.44 | No |

| Abiraterone | 21 | 42 | 1000 | 1 | No | |

| Enzalutamide | 1 | 2 | 160 | 1 | No | |

| Docetaxel | - | 26 | - | - | Yes |

DDD-Defined daily dose, PDD-Prescribed daily dose, NLEM-National List of Essential Medicines

Discussion

Bicalutamide was most commonly prescribed medicine in B0, B1 and CSPC. Bicalutamide 150 mg daily was prescribed until bilateral orchiectomy or initiation of LHRH-A, and then reduced to 50 mg daily, irrespective of tumour burden. According to the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group 6 study, continued use of bicalutamide 150 mg delayed disease relapse, but evidence in favour of overall survival will require longer follow-up as per NCCN guidelines (Thomsen et al, 2015; NCCN, 2019). Bicalutamide was given alone in those patients who opted for surgical castration and it was prescribed in combination with LHRH-A for medical castration. Thus, CAB was preferred over ADT monotherapy in all patients to maintain PrC in remission. Although, in western countries, CAB did not have better overall survival than ADT monotherapy, Japanese studies made a contradictory conclusion (Tamada, 2018; Yang et al, 2019). Nonetheless, CAB is known to symptomatically improve advanced PrC. ADT was primary and continuous in all patients. Although intermittent ADT entails the benefit of lower incidence of cardiometabolic and sexual adverse effects, it lacks data supporting it (Isbarn et al, 2009; Abrahamsson, 2017).

Patients with clinically and radiologically localised cancer underwent robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy, which is currently the gold standard for localised disease, after considering life expectancy and comorbid conditions (Hakenberg, 2018). Patients with aggressive and locally advanced tumours were given radiotherapy along with ADT, which is currently advocated by the American Cancer Society (ACS) and NCCN (ACS, 2019; NCCN, 2019). All B1 patients underwent radiotherapy and palliative pain care because of the high tumour burden.

For CRPC, abiraterone was the most commonly prescribed medicine, followed by fosfestrol, docetaxel-based chemotherapy and enzalutamide. Abiraterone had demonstrated an increase in overall survival of 4.4+ months with prednisolone compared to prednisolone alone in Phase III studies (de Bono et al, 2011). Moreover, the indication of abiraterone now includes both chemotherapy naive and resistant PrC and was started in all 6 patients with docetaxel resistance (Food and Drug Administration, 2019). More recently, it improved both overall and radiographic progression-free survival in metastatic CSPC in combination with ADT in the LATITUDE trial (Fizazi et al, 2017). Fosfestrol was preferred as a second line agent after progression with first line medicines, especially in resource-limited settings, as recommended in an Indian study (Kalaiyarasi, 2019). The general practice is to use cytotoxic chemotherapy in early CRPC to optimise benefits and manage adverse effects, rather than late in progressive disease. Among antiandrogens, enzalutamide had shown 4+ months increase in overall survival compared to placebo and is currently undergoing a phase 4 clinical study in India. It was prescribed only after other therapeutic options were exhausted in the set-up for the present study, because of its high cost (Scher et al, 2012; ClinicalTrials.gov, 2019; MIMS, 2019). However, bicalutamide could be a more cost-effective option and a recent open label phase 2 clinical trial showed that bicalutamide 150 mg could counteract castration resistance in CRPC (Klotz et al, 2014). It can be important for resource-limited settings. However, this finding needs evaluation in larger clinical trials and in the present set-up, bicalutamide 150 mg was not prescribed for CRPC.

WHO core indicators

Oral tablets were present in 96% of patients, while injectables were present in 48.7% of the prescriptions. As per WHO cut-off guidelines, injectables should be present in less than 30% (Ofori-Asenso, 2016). However, LHRH-A, marketed in depot injectable forms, is the first line treatment for PrC, rendering this core indicator inapplicable for this study (Lupron Depot, 2014). Antibiotics were prescribed in 3% of patients, which was lower than WHO limit of 30%. Antibiotics are not part of management and were only prescribed for patients with prostatitis or urinary tract infections. Prescriptions included medicines from NLEM, India (NLEM, 2015). Since medicines listed in it are subjected to pricing control by the National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority under Drug Prices Control Order 1995, these are relatively more affordable and accessible to the Indian population, as health expenditure in India is primarily out of pocket (Narula, 2015; Pandey et al, 2017).

Though the most common definition of polypharmacy sets the cut-off as ≥5 medicines, it is not a well-validated criterion (Viktil et al, 2007; Masnoon et al, 2017). In the present study, approximately 65% of the prescriptions contained >5 medicines; however, inappropriate prescribing practices were not observed.

Prescriptions for comorbidities

Among the antihypertensive medicines, amlodipine followed by hydrochlorthiazide, ramipril and metoprolol were commonly prescribed because of favorable safety profiles. Similar findings have been reported in the literature (Lim et al, 2015). Other antihypertensive medicines were less common. Among the antidiabetic medicines, metformin followed by sulfonylureas were most commonly prescribed. The PDD:DDD ratio for metformin was low, as it was used at lower dosages as a result of concern of renal dysfunction and lactic acidosis in elderly patients (Yakaryılmaz and Öztürk, 2017). Glimepiride was preferred because there are fewer adverse effects and better potency than other sulfonylureas (Basit et al, 2013). Very few prescriptions included antidepressant medicines. Paroxetine was prescribed at a higher dose, while lower dosages were used for escitalopram than WHO-DDD. Most patients complained of low mood, but the symptoms were not clinically significant and antidepressant medicines were not prescribed. Depression affects more than 1/10th of cancer patients, but the present study found shortfall in treatment and research to address the issue.

Conclusions

This study found that tumour burden and castration response-based management of PrC followed NCCN guidelines, for the most part. The WHO indicators were within limits. Though depression is a frequent comorbidity, antidepressant medicines were prescribed rarely. Comprehensive extension of drug utilisation methodology and core indicators of the WHO will provide competitive intelligence in prescription pattern analyses and rational therapeutics in oncology. More drug utilisation studies should be conducted in these diseases. Depression is a common co-morbidity in cancer patients. Screening for depression and its adequate management in cancer patients should be undertaken.

Key Points

- Multiple strategies are available for the management of prostate cancer and is primarily guided by tumor burden and castration response. Combined androgen blockade is first line of management in castration-sensitive prostate cancer patients.

- Abiraterone, an androgen synthesis inhibitor, is most commonly used drug in patients who developed castration resistance and cytotoxic drugs such as docetaxel is less frequently used.

- Core indicators of World Health Organization suggested frequent use of essential medicines.

- Polypharmacy was prevalent as per the WHO criteria but we suggest that it is appropriate in this disease.

- Depression is a common co-morbidity in prostate cancer but antidepressant medicines are prescribed rarely.

CPD reflective questions

- How can the use of polypharmacy as a core indicator be rationalised in cancer?

- Should antidepressant medicines be part of management protocol in prostate cancer patients?

- Should core indicators of the WHO be rationalised to the disease under study?