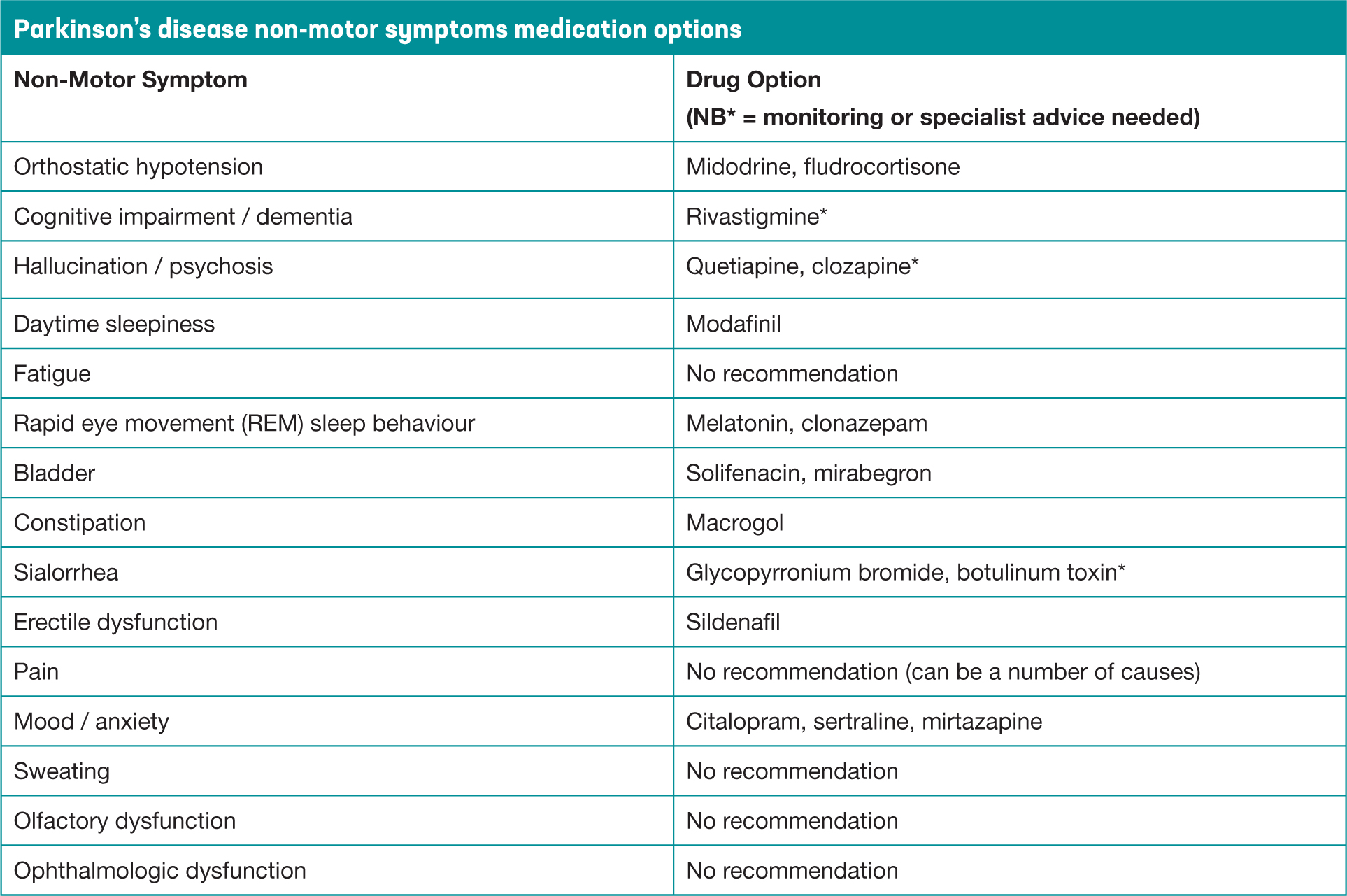

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a progressive neurological condition resulting from loss of dopamine producing cells, and the main treatment approach is therefore dopamine replacement therapy. While there is currently no known cure for this condition, effective medication management can significantly reduce the symptoms of PD and consequently improve quality of life. At the time of diagnosis the presenting features often relate to motor symptoms, namely bradykinesia, rigidity and resting tremor, as outlined in the PD Society Brain Bank criteria (Hughes et al, 1992). There is now greater understanding about the numerous PD non-motor features categorised as autonomic, neuropsychiatric, sleep and sensory symptoms, which can fluctuate and also respond to dopamine replacement therapy (Chaudhuri and Fung, 2016). Treatment options, for both motor and non-motor symptoms (NMS, Figure 1), should be discussed at diagnosis and feature in newly diagnosed patient education programmes. There are recognised stages of PD and the treatment approaches will vary in each, but the aim should be to optimise medication for maximum symptom control, while minimising the potential for any adverse side effects. It is acknowledged that treatment of NMS should also be considered throughout the disease trajectory and there is a growing evidence base to support treatment options across the spectrum (Seppi et al, 2020).

Figure 1. Non-motor symptoms in Parkinson's

Figure 1. Non-motor symptoms in Parkinson's

The Parkinson's disease nurse specialist (PDNS) is recognised as the accessible point of contact within the specialist service (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE], 2017), developing a therapeutic relationship and playing a pivotal role in medication management from time of diagnosis. This includes ensuring that the person with PD is given every opportunity to be fully involved in the process and make informed choices, aware that to date there are no known neuroprotective or disease modifying treatments (Kobylecki, 2020). The Parkinson's Disease Nurse Specialist Association (PDNSA) competency framework (PDNSA, 2016) identifies the skills and underpinning knowledge required by the PDNS non-medical independent prescriber to safely and effectively assess, titrate and monitor all aspects of prescribing practice.

There are numerous considerations relating to the timing of when to start medication and treatment approach, which will influence the prescribing decision process. Personal preference, lifestyle and concordance with medication can be key issues as PD medications are recognised as being time critical for effective symptom control. An individual personalised treatment plan will therefore encompass choice and the evidence-base for various treatment options. The decision to start treatment will be informed by functional ability and mobility, both of which are affected by the cardinal features of PD. There may be a reluctance to start levodopa on the part of the patient or prescribing clinician, and where this is due to misperceptions about either starting too soon, or misguided belief about side effects, it has been referred to as ‘levodopa phobia’ (Titova et al, 2018). However, it is suggested that levodopa should be considered as a first line treatment where motor symptoms are impacting on quality of life, and the PDNS is ideally placed to ensure patients are signposted to reliable sources of information. (NICE, 2017). The principles of considering medication options are outlined in the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS, 2016) competency framework for prescribers, which supports using the lowest dose possible, and titrating cautiously to achieve therapeutic benefit while monitoring for side effects. It is a legal requirement that all drivers with a diagnosis of PD inform the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency and insurance company of their diagnosis. Side effects of medication could have an adverse effect on ability and safety when driving (Parkinson's UK, 2019). It is advisable to carry a prescription copy of prescribed PD medications as it is an offense when driving to have blood levels of certain drugs without proof of this being a prescribed medication, including clonazepam, which is used for REM sleep disturbance in PD. Patients should be advised that when dopamine agonists are being initiated or titrated that they might experience increased daytime or sudden somnolence, which could impair driving ability and might therefore need to refrain during this period.

It is important that medication reviews are undertaken 6-12 monthly in conjunction with a PD specialist care team (NICE, 2017). Timing of reviews will also be influenced by the need to make more frequent changes to medication, as defined in the complex phase of PD (MacMahon and Thomas, 1998). Treatment approaches in PD are initially focused on oral options but when these are no longer effective non-oral approaches, which do not rely on first pass metabolism, would be considered (Price et al, 2018). The COVID-19 pandemic has had an unprecedented impact on clinical practice, and many specialist services have resorted temporarily to telephone or virtual consultations. This remote assessment has been particularly challenging in relation to determining whether symptoms are related to motor or NMS issues, and whether these have been exacerbated by the consequences of the pandemic restrictions (Helmich and Bloem, 2020). There is also an increasing awareness of different subtypes of PD attributable to differences in underlying pathophysiology and the implication of several neurotransmitter pathways other than the dopaminergic system (Jankovic and Tan, 2020). It is consequently understandable that patients may require a polypharmacy approach to manage their myriad of symptoms and complex needs.

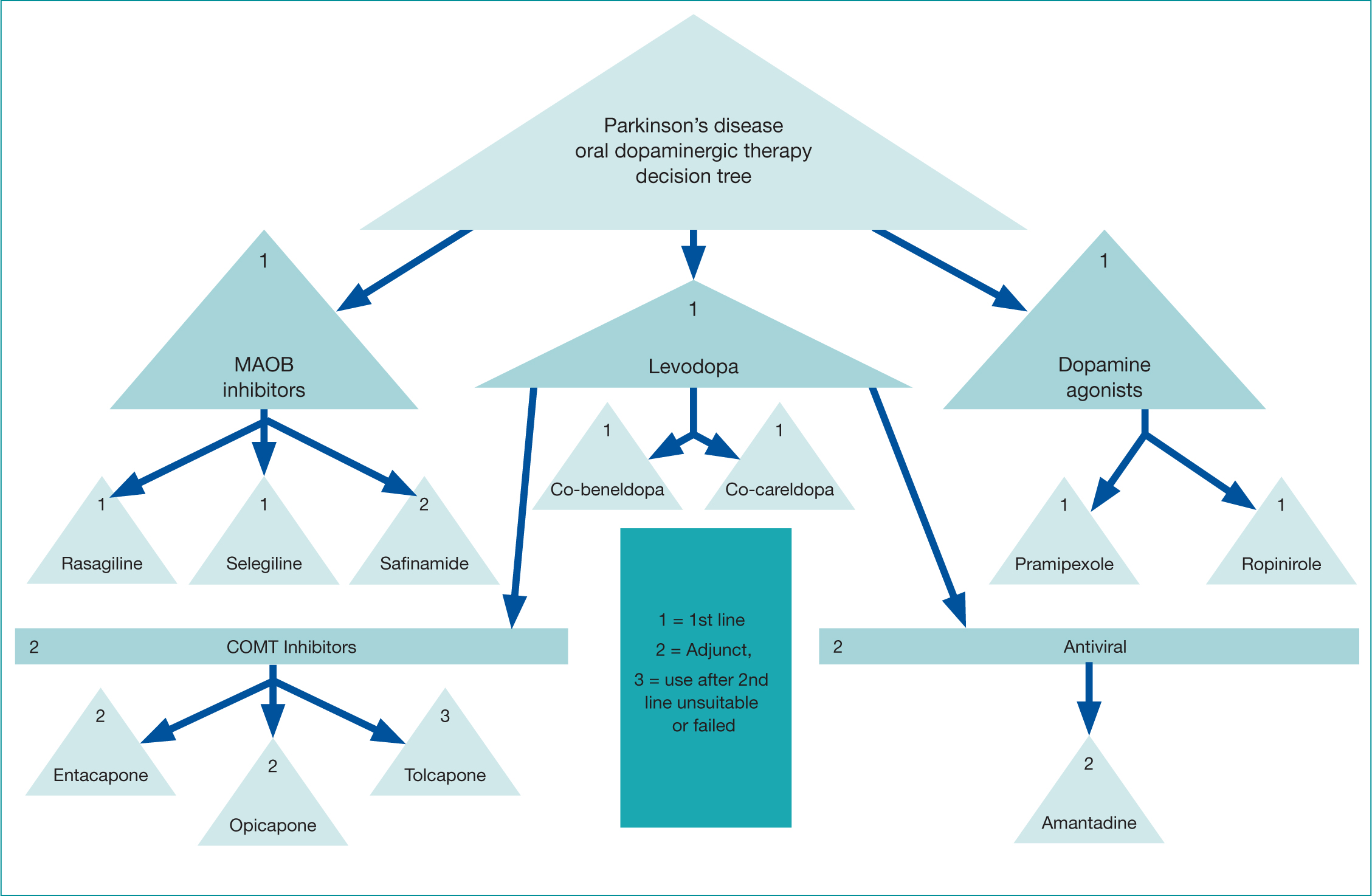

The various drug groups (Figure 2), treatment approaches and side effects are now discussed with consideration of how they might be used in conjunction, to improve efficacy, enhance response and improve symptom control.

Figure 2. Decision tree of drugs in Parkinson's

Figure 2. Decision tree of drugs in Parkinson's

Levodopa

People with Parkinson's (PwP) have depleted levels of dopamine in the brain. From the 1970s, levodopa, which is metabolised to dopamine, was utilised to treat the disabling motor symptoms. Initially the majority of levodopa was broken down in the small intestine without being absorbed into the bloodstream. This resulted in unpleasant side effects including nausea and motor fluctuations. When a dopa-decarboxylase inhibitor was later added, it reduced nausea and increased absorption in the small intestine so that more levodopa was available to be converted to dopamine in the brain (Rascol et al, 2011).

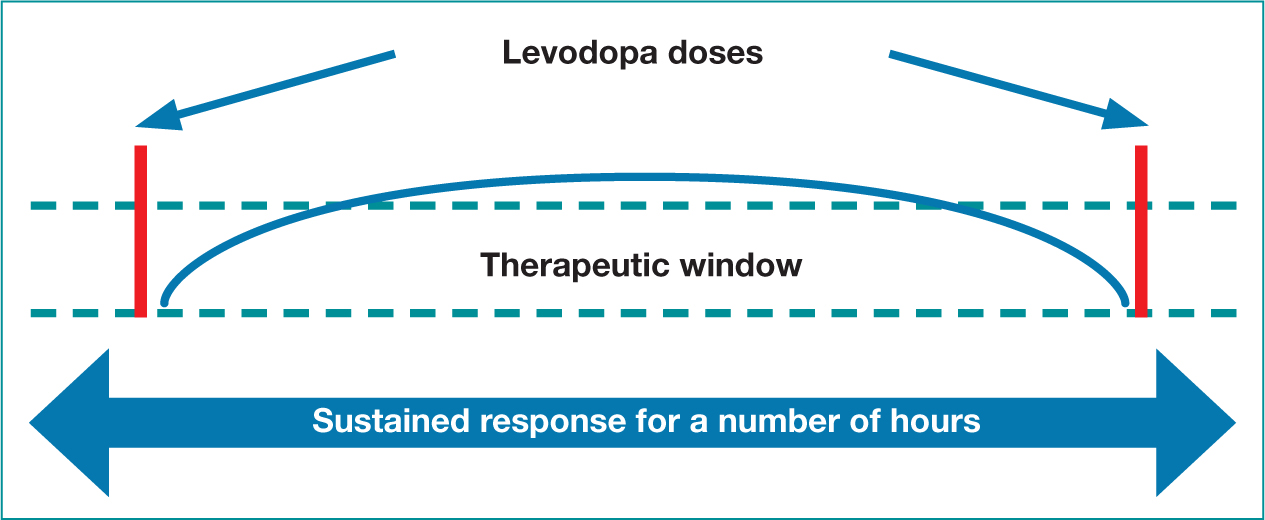

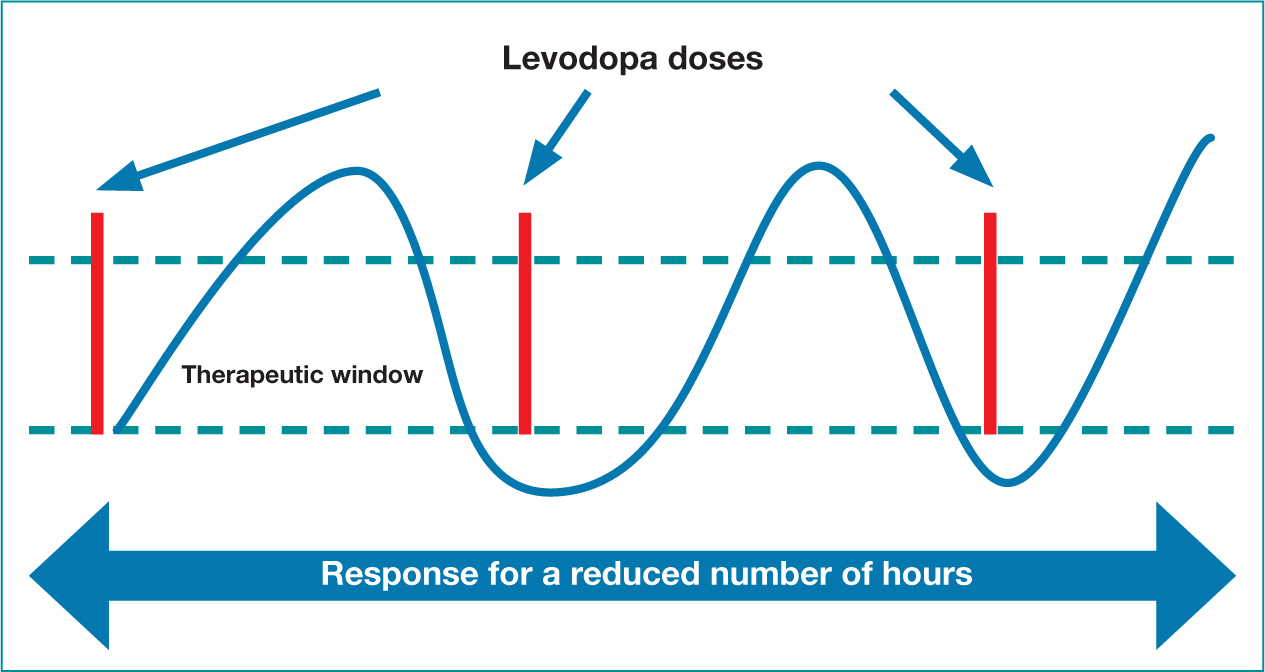

As mentioned, the NICE guidelines (2017) recommend levodopa can be offered first line in the early disease stage, and is unquestionably the most effective oral dopaminergic therapy (de Bie et al, 2020). It is currently available in two formulations and used throughout the disease trajectory either as a mono or adjunct treatment option, with patients reporting improvements in bradykinesia and rigidity. Levodopa has a half-life of approximately 90 minutes and the effects will initially last for several hours (Figure 3). As PD progresses, due to the continued depletion of dopamine producing cells, an increase in levodopa dosage and frequency will be required (Figure 4). Absorption can become erratic due to issues such as delayed gastric emptying, and the resulting narrow therapeutic window, leads to fluctuating motor responses such as dyskinesia, ‘wearing off’ or immobility. Therefore, Levodopa is a time critical medication, as getting medication on time can help address issues such as end of dose effect. Prescribers should therefore write the timing of doses on the prescription, as this may aid concordance and recognition of the time critical element.

Figure 3. Initial levodopa dose response

Figure 3. Initial levodopa dose response  Figure 4. Levodopa dose fluctuations

Figure 4. Levodopa dose fluctuations

Issues may also occur around the brands of levodopa, with lack of clarity around immediate release (IR) or controlled release (CR) preparations. An example of a common medication error is when prescribing co-careldopa IR 25/100 mg or prescribing co-careldopa 25/100 mg CR. A commonly used branded preparation is named ‘Half Sinemet 25/100 mg CR’ while the IR preparation is named ‘Sinemet Plus 25/100 mg’. The CR preparation has reduced bioavailability in comparison to the IR preparation and in effect this could result in reduced symptom control if taken/prescribed in error. It has also been noted from medication reviews that a PwP might have been prescribed either ‘half a tablet’ instead of Half Sinemet CR, again resulting in a lower dose being taken than intended. It is suggested that there is no significant clinical advantage to taking controlled release preparations of levodopa during the day time (Chaudhuri and Fung, 2016), and could even result in patients experiencing a delayed effect to motor symptom improvement. In contrast, a CR preparation of levodopa at night might be better tolerated and help nocturnal immobility.

Oral dopamine agonists

This class of drug has a similar effect to that of levodopa, however, their mode of action differs. Oral dopamine agonists (DAs) mimic the effect of dopamine in the brain rather than actually increasing the levels, binding to and stimulating dopamine receptors (Antonini et al, 2009). They are available as IR or modified release (MR) preparations. Similar to levodopa, this class of drug can be offered at diagnosis (NICE, 2017), or can be added later as an adjunct therapy (Figure 2). DAs can be particularly helpful where patients may have issues with concordance, as the MR preparation is taken just once a day. DAs have been associated with reduced motor fluctuations in comparison to levodopa, and when used in combination with levodopa may delay the need to escalate the dose of levodopa, which in the long term may reduce risk of severe motor fluctuations (Schapira, 2006).

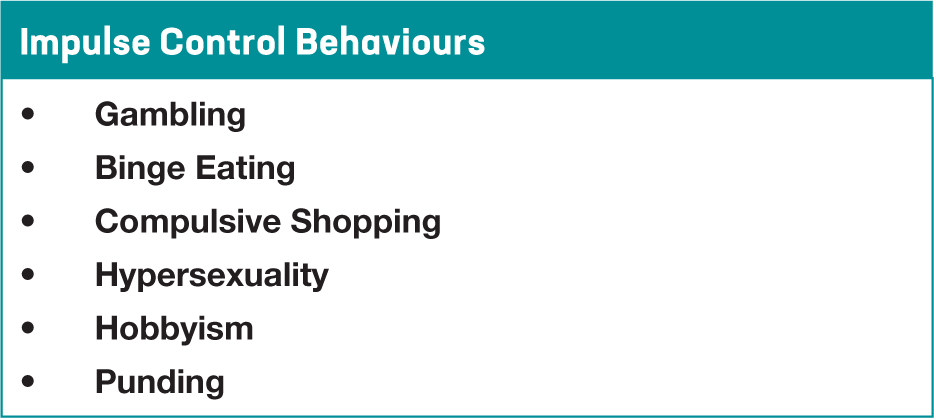

When commencing DAs, history of risk or habit-forming behaviours (Figure 5), and neuropsychiatric issues must be considered. DAs in MR form have a longer duration of action, potentially helping with nocturnal akinesia (Pellicano et al, 2013). It was initially thought that the MR preparations of DAs would work for 24 hours. However, patients report a reduced effectiveness towards the end of dose and therefore it is usually prescribed to be taken in the morning, so that the patient is asleep when there might be reduced efficacy. When prescribing or reviewing medications it is important to check the intended formulation of either IR or MR, as again any error could seriously impact symptom control and potentially cause concerning side effects which are discussed later. Caution is also strongly advised when prescribing the drug pramipexole as the strength is expressed with two different values (salt or base) for the dose required, and consistency in this prescribing format is essential to reduce the risk of the patient being given the wrong strength.

Figure 5. Impulse Control Behaviours in Parkinson's

Figure 5. Impulse Control Behaviours in Parkinson's

Monoamine oxidase B inhibitors

Monoamine oxidase B inhibitor (MAOB-I) drugs are recommended by NICE (2017) for early monotherapy or as an adjunct therapy (Figure 2). They work by inhibiting some of the MAOB enzyme in the brain, resulting in an increased level of dopamine availability, either naturally occurring or that metabolised from levodopa (Labin and Saadabadi, 2020). These inhibitors work along the same pathways as serotonin and should be avoided with the use of a selective serotonergic reuptake inhibitor, notably fluoxetine and fluvoxamine (Joint Formulary Committee, 2021), as this interaction could cause serotonergic syndrome with potentially serious or even life-threatening consequences (Aboukarr and Goudice, 2018). Rasagiline and Selegiline are once daily MAOB-I drugs, but these days the latter is less frequently used due to potential neuropsychiatric side effects. The latest MAOB-I is Safinamide which is licensed as an adjunct therapy according to prescribing formularies across the United Kingdom (UK), patients should have first been trialled and failed on one of the other MAOB-I drugs before considering this as a treatment option.

Catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitors

Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitors are an adjunct drug, used with levodopa. The mode of action is to reduce the amount of levodopa being broken down peripherally or centrally, thereby increasing the amount of levodopa available for conversion to dopamine (Jancovic, 2020). COMT therefore has the effect of a dose of levodopa working stronger and longer without having to increase the actual dose, which would help with symptoms of ‘wearing off’ at end of dose. It is also suggested that this would enable the levodopa dose to be kept as low as possible, which would potentially reduce the risk of severe motor fluctuations and dyskinesia in the long term (Fox et al, 2018).

Tolcapone was the first COMT available, but is not currently widely used as it requires strict blood monitoring for liver function due to incidence of hepatotoxicity in some patients (Artusi et al, 2021). The next generation COMT's (Figure 2) are available as entacapone 200 mg and opicapone 50 mg. Entacapone 200 mg only works on the dose of levodopa that it is taken with, and therefore if taken several times a day would significantly increase pill burden for the patient. If tolerated, a combination preparation of levodopa / carbidopa / entacapone could be used which would reduce the number of pills taken. These combination preparations could also prove particularly useful as they provide a greater range of levodopa dose options, enabling a more personalised dosing schedule. A recognised potential adverse side effect of entacapone is that it can cause discolouration of urine that could stain underwear, but also gastric disturbance, bloating and loose stools which, if it does not settle after a few days, would necessitate discontinuation.

Opicapone is the newest of the COMT inhibitors and is a once daily drug, taken one hour before or after the last levodopa dose. The reason it is taken at night is to avoid the majority of the levodopa drug absorption issues (Svetel et al, 2018). In most areas around the UK, prescribing guidelines indicate that patients must have first been considered for entacapone and that this is not an appropriate treatment option. One advantage of opicapone is that it provides a longer duration in its inhibition, potentially helping with early morning rigidity, bradykinesia and immobility. A second advantage is that this medication does not have the same potential gastrointestinal adverse effects associated with entacapone and can therefore be considered when diarrhoea has resulted in discontinuation of entacapone. Opicapone is a potent COMT inhibitor with increased efficacy (Fox et al, 2018), and patients may often require a reduction of their levodopa a few weeks after commencing this COMT, as the enhanced effect could cause or exacerbate dyskinesia.

Amantadine

Amantadine is an antiviral drug that has a mild effect on PD symptom control. It is used as an adjunct, to reduce troubling dyskinesia not alleviated by modifying the other PD medications (NICE, 2017). This medication can have an alerting effect and therefore it is important that it is not taken too late in the day, no later than 2pm, as this could disrupt the usual sleep pattern. Possible side effects include reports of patients feeling overexcited or anxious and it is important to monitor for any neuropsychiatric issues including hallucinations, delusions or paranoia. Patients also need to be aware of the less common side effect of livedo reticularis, a purplish lacey discolouration on the lower legs that eventually resolves once the medication is stopped (Neimann et al 2021).

Deprescribing

With disease progression and complexity, it may often be necessary to reduce PD medications where side effects outweigh the benefit. Deprescribing can be an important and necessary aspect of effective PD management, especially where there is the need to consider medications to address neuropsychiatric issues as these drugs often have a dopamine blocking effect.

Complex issues in Parkinson's disease

Disease progression and continued neuronal loss leads to diminished efficacy of oral medications and a comprehensive assessment will best inform future management (Grosset et al, 2009). Throughout the disease trajectory, the aim is to keep the levodopa at the lowest therapeutic dose possible, suggested total daily dose of 600 mg or less (Clarke, 2007). As discussed earlier, adding adjunct therapies can help to achieve this but in the complex phase, they may need to be withdrawn due to the enhancing effect contributing to any non-motor neuropsychiatric issues.

During the complex stage, neuropsychiatric symptoms including visual hallucinations and cognitive issues can become more pronounced. PD dementia can occur in approximately 80% of cases, and is associated with increased mortality (Postuma et al, 2012). Timely medication reviews with a downward step wise approach should be initiated, withdrawing the drugs that are most likely to be least tolerated first. Deprescribing of drugs in suggested order would be anticholinergics, MAOB inhibitors, amantadine, DAs, COMT, with levodopa being the final PD drug remaining at the lowest possible dose (Taddei et al, 2017). NICE recommends that the cholinesterase inhibitor Rivastigmine should be considered for patients at all stages of PD dementia (NICE, 2017). Nausea can be a common side effect of Rivastigmine although the patch formulation is generally better tolerated (Sadowsky, 2010).

If hallucinations are mild and well tolerated, no intervention might be necessary. If treatment is required, Quetiapine is recommended due its tolerability with less adverse effects on motor function. It should be noted that in patients with PD it is important to start with much lower doses than would otherwise be considered. Where Quetiapine has not been effective, the treatment of choice would be Clozapine, an atypical antipsychotic, but is not readily available in all specialist centres. Clozapine can only be prescribed by a Clozapine registered practitioner, with a strict protocol for review and blood monitoring, which could be challenging for the clinician and especially the patient to maintain (Kar et al, 2016).

As discussed earlier, impulse control behaviours (ICBs) can be attributable to adverse effects of some PD drugs (Figure 5). Whist this is potentially an adverse side effect of any dopamine replacement therapy, it is more closely associated with the use of dopamine agonists. Impulse control disorder (ICD) has been defined as the inability to resist an urge, which can then present as ICBs. These behaviours might be harmful to the person or others, and typically involve repetitive, reward-based actions with the individual experiencing loss of control (Kelly et al, 2020). It is therefore imperative that PwP and their families are counselled and closely monitored to inform prescribing decisions.

While ICD is more often associated with DAs, dopamine dysregulation syndrome (DDS) is more often linked to levodopa usage. This is described as a craving for increasing dosage of medication and likened to addiction (Chaudhuri and Fung, 2016). Close liaison between the PD clinician and GP are needed to monitor prescriptions and concordance with intended drug regimen. With both ICD and DDS, the treatment approach is to support the patient with a very gradual down titration of medication to alleviate potentially devastating and distressing drug induced symptoms. The issues can vary in presentation and severity which may be dose dependant and resolve with even slight reduction in medication. It is crucial that down titration of a DA is slow and closely supervised to reduce the risk of dopamine agonist withdrawal syndrome (DAWS) which can present as anxiety, panic attacks and drug cravings (Rabinak and Nirenberg, 2010).

A serious complication resulting from a sudden cessation of PD medications could be neuroleptic malignant syndrome. This is a rare but life-threatening medical emergency manifesting as, fluctuating consciousness, fever, severe muscle rigidity, hypertension and renal failure. It is imperative the PD medication is urgently restarted and any dopamine blocking agents are reviewed (Alty et al, 2016). If oral medications cannot be reinstated an alternative route of administration will be necessary following local nil by mouth guidelines.

A common adverse effect PD medication is orthostatic hypotension which can lead to falls and increased morbidity and mortality (Wu and Hohler, 2015). Orthostatic hypotension can be a side effect of medication or part of the disease process. A comprehensive review of all medication will help to identify any possible pharmacological causes. Levodopa acts as a peripheral vasodilator with the effect of lowering blood pressure (Noack et al, 2014). PwP who might have previously been hypertensive and on medication to manage this, would benefit from medication review to consider if it is still needed. If patients experience significant and ongoing orthostatic hypotension, despite non-pharmacological interventions, Midodrine is the first line treatment (NICE, 2017). Patients will need to be monitored for potential supine hypertension, and therefore this drug should not be prescribed to be taken at bedtime. If Midodrine is contraindicated or not tolerated, Fludrocortisone can be initiated, mindful of contraindications where there are congestive cardiac or renal failure issues (Wu and Hohler, 2015).

Deprescribing and end of life

As PD advances towards the end of the disease trajectory, symptoms of pain, fatigue, insomnia, dyspnoea, dysphasia and dysphagia can be very distressing for both the PwP and the caregiver (Higginson et al, 2012). These symptoms can often occur with agitation and worsening cognitive decline, exacerbating what are often already very complex care needs. Rationalisation of all medications will help to determine the balance of benefit compared to adverse side effects.

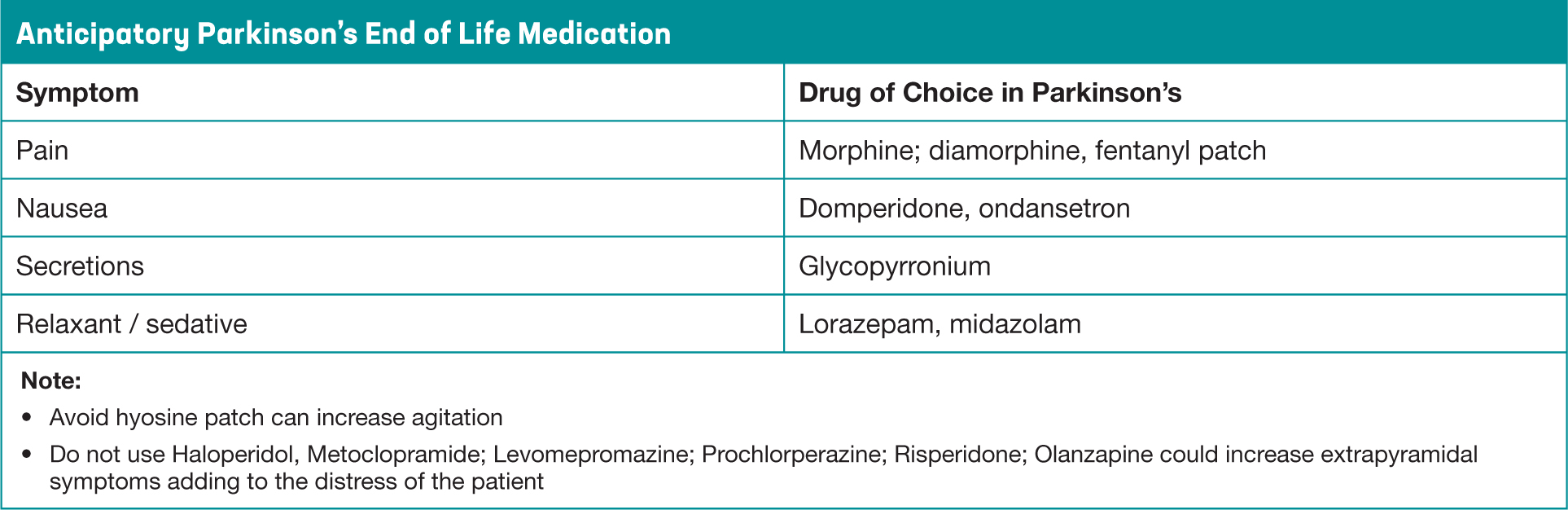

Anticipatory care planning for end of life will help to plan for any potential symptoms that can arise (Figure 6). The most common symptoms are pain, dyspnoea, nausea and vomiting, agitation, anxiety, delirium and noisy respiratory secretions (Davie, 2012). It is crucial that drugs used to alleviate these distressing end of life symptoms do not exacerbate the motor features of PD that could in turn increase discomfort

Figure 6. Anticipatory End of Life Medication in Parkinson's Disease

Figure 6. Anticipatory End of Life Medication in Parkinson's Disease

If PD medication was suddenly withdrawn, there is the possibility of neuroleptic malignant syndrome, a life-threatening and distressing condition resulting in rigidity and fever (Jones et al 2011). To reduce this risk, alternative means of drug delivery may need to be considered, to keep the patient as comfortable and distress free as possible. Complex dopaminergic treatment regimens should be simplified as much as possible, dispersible or liquid forms of levodopa are available, and oral DA's can be switched to a Rotigotine transdermal patch. While advice should always be sought from the specialist PD team, suggested conversions are available with the online PD drug calculator (British Geriatric Society, 2018). Continuing medication in Parkinson's at the end of life is also important, as it can be helpful in reducing pain from rigidity. Always consider the lowest recommended doses, to prevent unwanted side effects in these advanced stages, including a drug induced psychosis or agitation.

Conclusion

Management of PD symptoms depends largely on effective management of oral medications. It is acknowledged that neurotransmitter systems other than the dopaminergic system are implicated and a comprehensive approach, particularly to address non-motor symptoms may include treatments other than dopamine replacement therapies. All clinicians involved in the medication decision making process must approach this with the individual at the forefront. This personalised approach will help to effectively manage the unique symptom presentation while risk managing the potential for what can be devastating adverse effects of treatments that can impact on the person with PD and their family. Timely medication reviews and access to a health professional such as the Parkinson's disease nurse specialist, can then help to recognise issues that can be addressed at the earliest opportunity.

Key Points

- Effective medication management can improve PD symptom control.

- There are different medication management approaches at each stage of PD

- Due to disease progression, oral medication will become less effective in controlling all symptoms over time

- As oral medications become less effective, PwP can experience increased motor fluctuations

- It is important that PD medication is taken at individually prescribed times, recognised as time critical medication for optimal symptom control

- The PDNS plays a key role in all aspects of PD medication management

CPD reflective questions

- Why might a PwP be reluctant to start levodopa at time of diagnosis?

- Which group of PD drugs are of particular significance when a PwP is being considered for antidepressant medication?

- If a patient becomes nil by mouth, why is it important that PD treatment is not just suddenly stopped?

- What behaviours might be suggestive of an impulse control behaviour?

- If a PwP or relative reports any behaviours suggestive of impulse control disorder, what treatment approach must be taken to avoid DAWS.