Various resources, support and guidance are available to enable safe prescribing practice in sexual and reproductive health. The speciality is supported by the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (FSRH) evidence-based clinical guidance, clinical and service standards, members' enquiry email service and UK Medical Eligibility Criteria (UKMEC) for contraceptive use (FSRH, 2018).

These resources should be used in conjunction with other prescribing resources such as local formularies (eg Lothian Joint Formulary), summaries of product characteristics and the British National Formulary to ensure that prescribing practice meets local and national guidance and expectations so that patients receive consistent information and administration of medication (Akici and Sirvanci, 2012).

The combined hormonal contraception national guidance document provides evidence-based advice on contraindications, risks, recommendations for clinicians, consultation requirements and prescribing guidance (FSRH, 2019). Local prescribing resources advise on current recommendations for first- and second-line drug choices taking into consideration cost, local availability, new drug decisions and best practice (NHS Lothian Joint Formulary, 2011).

This article will focus on the combined hormonal contraception guideline due to the significant changes to recommendations for prescribing.

Clinical relevance and implications for practice

There are two main changes in the guidelines that will have implications for prescribing practice. The guidelines recommend that eligible women can be prescribed a 12-month supply of combined hormonal contraception at initial consultation, rather than a 3-months' supply as previously recommended. The new guidelines also focus on ‘tailored regimes’. A tailored regime is a way of taking combined hormonal contraception that differs from the ‘traditional regime’. In a traditional regime, women take combined hormonal contraception for 21 days followed by a 7-day break. This regime will be the most familiar to women and health professionals (Akintomide et al, 2018).

There are many benefits of omitting (or shortening) the 7-day break, including reduced bleeding, reduced side effects in the break, increased compliance and possibly reduced risk of ovarian activity that occurs due to the unintentional extension of a 7-day break (Birtch et al, 2006).

Women should now be given the option of either the traditional regime or a tailored regime, which can include ‘shortened hormone free interval’, ‘extended regime’, ‘flexible extended regime’ or ‘continuous regime’ (Table 1) (FSRH, 2019).

Table 1. Standard and tailored regimens for use of combined hormonal contraception

| Type of regimen | Period of combined hormonal contraception use | Hormone-free interval |

|---|---|---|

| Standard use: | 21 days (21 active pills or 1 ring, or 3 patches) | 7 days |

| Tailored use: | ||

| Shortened hormone-free interval (HFI) | 21 days (21 active pills or 1 ring, or 3 patches) | 4 days |

| Extended use (tricycling) | 9 weeks (3 x 21 active pills or 3 rings, or 9 patches used consecutively) | 4 or 7 days |

| Flexible extended use | Continuous use (≥21 days) of active pills, patches or rings until breakthrough bleeding occurs for 3–4 days | 4 days |

| Continuous use | Continuous use of active pills, patches or rings | None |

Prescribing should be regarded as shared decision-making between the patient and the prescriber (Baird, 2004), and patient involvement requires acknowledgement of patients' views about their condition and treatment (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2009). There may be concerns about patient involvement increasing the overall length of consultation; however, NICE (2009) highlights the benefits of shared-decision making particularly with long-term conditions and treatments. Discussing the different contraceptive regimes with women and working with them to effectively establish the most suitable option should lead to better adherence. It may be beneficial to develop a leaflet for patients detailing the new regimes (Appendix), which may also help time management and ensure that patients have clear understandable information that they can refer to after the consultation.

The ability to offer a 12-month supply at initial consultation is a significant and welcome change. Previously, when administering a 3-month supply there was a concern about women being able to access an appointment before they have run out of contraception. Having the option to provide up to 12-months' supply gives women flexibility. Shared decision-making between the patient and prescriber will enhance concordance and possibly reduce discontinuation, which will therefore reduce the risk of unplanned pregnancy (FSRH, 2019).

Some practitioners may be concerned about side effects or adverse events not being addressed due to the lack of return visit. One study also found that increased pill wastage was associated with the greater number of pill packs prescribed (Foster et al, 2011). Steenland et al (2013) highlight a further concern about prescribing a 12 month supply of combined hormonal contraceptive initially; women may not return earlier as advised if they start suffering from adverse effects. However, the combined hormonal contraceptive guideline (FSRH, 2019) discusses the importance of ‘safety netting’ to ensure that patients are aware that they can return sooner and what the indications are to for a hastier return.

As a prescriber it is important to have honest discussions with patients and ensure that they are aware of the risks of any medication prescribed, and that they have written information and contact numbers should they suffer any adverse effects or have any concerns. Jones et al (2019) highlighted the importance of giving safety netting advice. Kaufman (2008) believed that it empowers the patient and protects the practitioner. Empowering patients and involving them in decisions about their care aids concordance.

Prescribing resources

It is important to adhere to evidence-based guidelines and work within a legislative framework to ensure safe and appropriate prescribing (Scottish Government, 2006).

UKMEC (2016) provides evidence-based guidance on which women can safely use each contraceptive method. The UKMEC guidance is adapted from the World Health Organization's Medical Eligibility Criteria and is an invaluable resource when discussing and prescribing contraception. The UKMEC is easily accessible online and can be used when discussing safety and contraindications with patients and to evidence decision-making.

The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) and NICE are both responsible for providing national guidance on the promotion of good health with the intention to improve healthcare for patients.

Local and national formularies provide recommendations for prescribing. The local joint formularies have many benefits for patients allowing a consistent approach to treatment, a smooth link in prescribing between primary and secondary care as well as being cost-effective (Reynolds et al, 2012). However, local formularies can feel restrictive and prevent freedom in prescribing (van der Kleijn et al, 1998) although the consistency offered to patients between prescribers being guided by local formularies is important to prevent confusion and conflicting information. This is especially important when prescribing combined oral contraception because there are many different brands of the same drug, so if primary and secondary care practitioners use the local formularies, it can reduce confusion and switching between brands. Even though local formularies can limit professional autonomy and patient choice they do encourage high quality and cost-effective prescribing, which is important for the NHS (Fairley, 2006). Reynolds et al (2012) also highlighted that one of the major advantages of having a local formulary is that it becomes possible to make changes rapidly as new information becomes available, which will clearly be beneficial in the dissemination of information about the new combined hormonal contraceptive recommendations.

Impact on prescribing practice

High quality, effective and consistent prescribing is enhanced by the contribution of the whole multidisciplinary team (Mair et al, 2016). All members of the multidisciplinary team should have a common goal of providing consistent, high-quality patient care with safe prescribing practice.

Clinical governance encompasses accountability for safety, effectiveness, quality, and improved clinical care (Scottish Government, 2006). The new recommendations in the FSRH guideline will need to be implemented by the whole multidisciplinary team to ensure patients can attend either primary or secondary care and obtain the same high level of care and current advice. This is highlighted by Anderson et al (2018) who reported on pharmacists prescribing contraception. However, it is notably difficult to change a practice, which has been embedded in prescribing for generations. It is therefore important to have clear processes and good communication to enable shared care between primary and secondary care. Clear communication, effective collaboration between patients and health professionals and smooth continuity of care are key elements of safe and effective prescribing (NHS Lothian, 2016). Patients should have equitable access to medicines across secondary and primary care (NHS Lothian, 2016) and prescribers should show accountability for effective communication to reduce inconsistent advice. Yet accountability is more than just responsibility, it involves having the ability and appropriate knowledge for all aspects of prescribing decisions (Scottish Government, 2006).

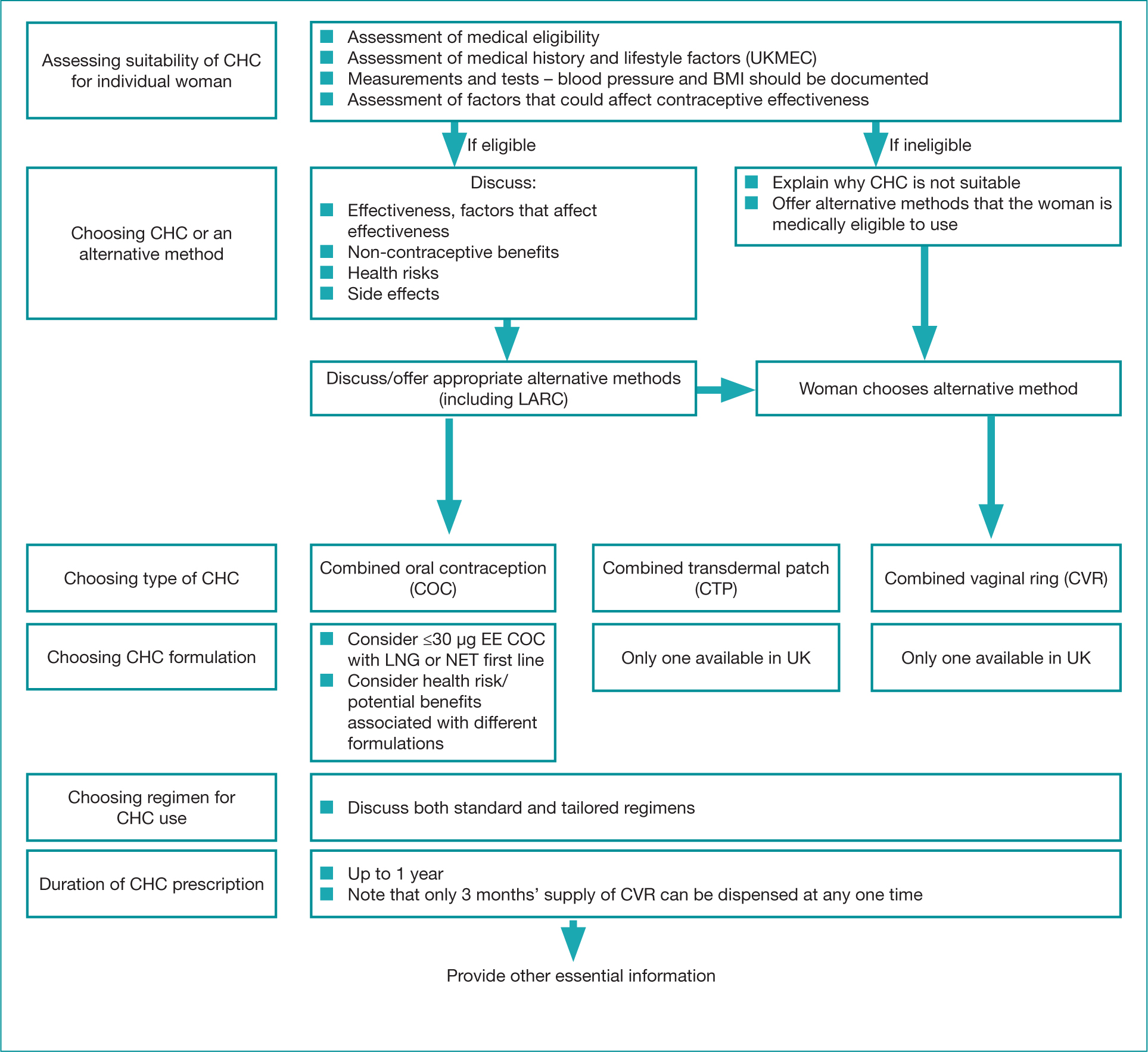

It is important to communicate the new guidance both locally and nationally and the FSRH have widely advertised the new guideline in professional journals, social media, webinars and national conferences. All members of the multidisciplinary team should be aware of the recommendations and resources available to aid effective working relationships and a consistent approach to prescribing combined hormonal contraceptives (Robinson, 2016). The FSRH guidelines also includes a ‘consultation template’ (Figure 1), which highlights all necessary aspects of a combined hormonal contraceptive consultation, but with such a prescriptive outline it may feel restrictive to prescribers; however, it is important to standardise essential requirements (Robinson, 2016). Standardisation can also help to reduce prescribing errors (Health Improvement Scotland, 2014).

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society (2016) produced A Competency Framework for all Prescribers, which encompasses 10 components under two umbrella headings of ‘the consultation’ and ‘prescribing governance’. This framework is an excellent comprehensive tool for prescribers that keeps the patient at the centre of all decisions and can be used in conjunction with the resources already mentioned.

Hoffman et al (2004) examined the importance of nurses making decisions with patients and factors that influences these decisions. Discussions during consultations will change as the shared decision of what regime and length of supply is most appropriate and acceptable to the patient become more variable. All available options should be considered and discussed with the patient and expectations and preferences should always be considered when deciding on a treatment option.

Off-license use

Although tailored regimes are accepted and recommended practice, they still remain ‘off-license’ use (FSRH, 2019). Nurse independent prescribers can prescribe medications for use out with their licensed indications; however, they must accept clinical and legal responsibility for that prescribing and should only prescribe off-license where it is accepted clinical practice (Scottish Government, 2006). The FSRH (2018) highlights that prescribers should be aware that this may alter their professional responsibility and potential liability, but also clarifies that off-license use may become necessary if the clinical need cannot be met by licensed medicines within the marketing authorisation. The Care Quality Commission (2018) states that there are clinical situations when the use of medicines outside the terms of the licence (‘off-label’) may be judged by the prescriber to be in the best interest of the patient on the basis of available evidence. However, it stresses that it is important discuss this and seek consent from patients to ensure safe prescribing and enable informed decision-making.

Mansour and Trueman (2004) stated that in everyday practice clinicians use licensed products in an off-licensed way and this can be justified if the particular off-licensed use is well established and endorsed by a professional body.

Conclusion

Guidelines and formularies improve the quality of patient care by ensuring evidence-based practice and prescribing. However, flexibility is also important to ensure that individual patient's needs and preferences are taken into account. As a prescriber there is an ethical responsibility to ensure prescribing decisions are in the best interest of the patient while also ensuring that prescribing is cost-effective and appropriate.

Patient preference can significantly influence prescribing practice. Patients should be educated by prescribers to allow them to make informed decisions that are right for them, but also safe. Shared decision-making addresses these issues and ensures that patients have access and understand the evidence-based information of all available options to make safe and appropriate decisions.

Key Points

- The new combined hormonal contraceptive guidelines recommends: up to 12 month initial supply; tailored regimes discussed with all patients; no change to medical eligibility or missed pill/patch/ring rules

- Prescribers should ensure safety netting is in place

- Shared decision-making will help concordance with contraception

CPD reflective questions

- What do you think some of the benefits would be for women of tailored regimes when using combined hormonal contraception?

- How could you help women to remember the various options for taking combined hormonal contraception?

- In what circumstances may a 12 month initial supply of combined hormonal contraception not be appropriate?