Adherence is the term currently used to describe a patient following prescribed or suggested treatment regimens; in other words – the degree to which a patient correctly follows medical advice (Bell et al, 2007). Adherence was previously, and sometimes concomitantly, known as compliance and concordance, however these terms are not synonymous (Bell et al, 2007). Concordance does not refer to a patient's medicine-taking behaviour, but instead the nature of the interaction between clinician and patient (Bell et al, 2007).

Adherence is regarded as a major problem in all pharmacological interventions, with approximately half of all patients with chronic diseases not adhering to their medical regimens, so is not specific to respiratory diseases (Jungst, 2019).

Commonly, adherence refers to medication or drug compliance, but it also applies to interventions, such as the use of medical devices, self-directed exercise programmes, self-care, self-management, and therapy sessions such as pulmonary rehabilitation. It is known that both the person receiving the advice or prescription and the healthcare provider affect adherence, and it is said that a positive physician-patient relationship is the single most important factor in improving adherence; this finding has been consistent over time (World Health Organization (WHO), 2003; Mathes et al, 2014). The cost of prescription medication may also play a major role in adherence to therapies, although in 2016, 89.4% of prescriptions dispensed in England were free of charge so it is not the whole answer (National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2009; NHS Digital, 2016).

Nonadherence

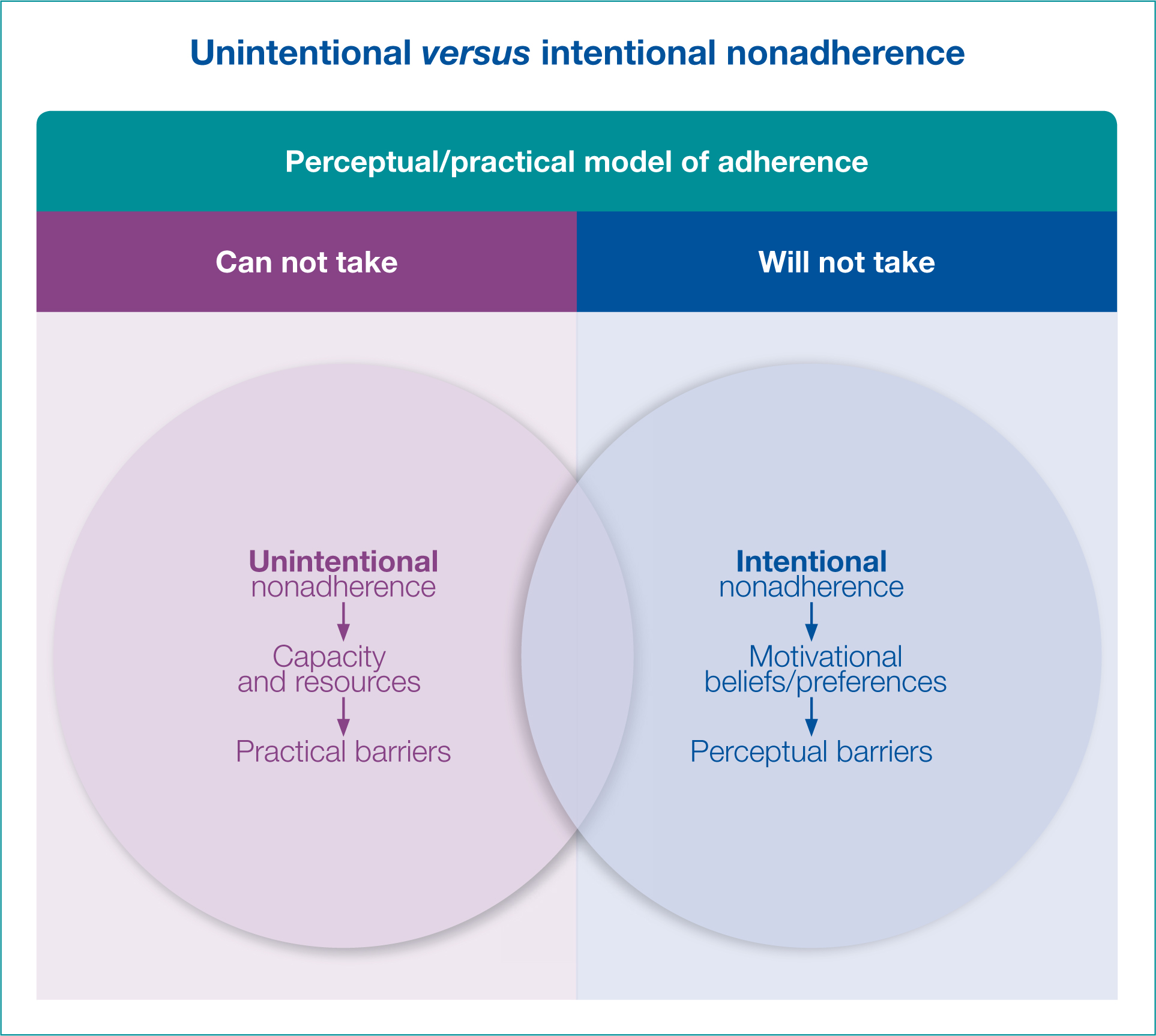

If adherence means compliance with recommended or prescribed therapy, nonadherence just means that the prescription, treatment or advice is not followed (Horne, 2005). Nonadherence can involve incorrect use, under or over use, or it not being used at all (Horne, 2005). There can be intentional nonadherence, where there is deliberate intent not to take the prescription, treatment or advice, or there can be unintentional nonadherence, where external factors cause the nonadherence. Nonadherence can vary over time, with the reasons for it changing, and one person can alter in their nonadherence behaviour over time (Horne, 2005).

Perhaps the most commonly used model for intentional and unintentional adherence is by Horne (Figure 1), looking at barriers between the necessity for having a medication and concerns over taking it (Horne, 2005).

Horne (2005) proposed that unintentional nonadherene is dependent on issues such as the persons' capacity to take the medication based on, for example, mental capacity and physical ability. Unintentional nonadherene may therefore may be beyond a person's control (Horne, 2005). Intentional nonadherence occurs when someone has decided that the advice of a medical professional will not be followed, the reasons for this ranging from personal or cultural beliefs, to inconvenience, or deciding that the side effects outweigh the benefits (Horne, 2005). An earlier categorisation of adherence grouped barriers to medication adherence into five categories; healthcare team and system-related factors, social and economic factors, condition-related factors, therapy-related factors, and patient-related factors (Table 1) (WHO, 2003).

Table 1. Barriers to medication adherence

| Barrier | Category |

|---|---|

| Poor patient-provider relationship | Healthcare team and system |

| Inadequate access to health services | Healthcare team and system |

| High medication cost | Social and economic |

| Cultural beliefs | Social and economic |

| Level of symptom severity | Condition |

| Availability of effective treatments | Condition |

| Immediacy of beneficial effects | Therapy |

| Side effects | Therapy |

| Stigma surrounding disease | Patient |

| Inadequate knowledge of treatment | Patient |

Whilst these remain relevant, there are other factors that might affect adherence, such as health literacy (WHO, 2015). Health literacy is the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and the services needed to make appropriate health decisions (WHO, 2015). The WHO (2015) defines the issue as ‘the personal characteristics and social resources needed for individuals and communities to access, understand, appraise and use information and services to make decisions about health’, indicating that this is a personal, societal and health service issue.

Actual literacy is also important, with the average reading age in the United Kingdom said to be about 9 years old, meaning around 1.7 million adults in England have literacy levels below those expected of an 11-year-old (GOV.UK, 2016). Therefore, understanding written information may be difficult, and we need to address this when we give out written materials. We also need to think about people from other ethnic backgrounds, their ability to read English and their cultural beliefs. A systematic review of adherence found ethnic minorities appeared less adherent, although the reasons for this were not stated and could be multi-factorial (Mathes, 2014). A person's level of education may also be important in adhering to medication regimens. Higher education and employment seem to have a positive effect on adherence (Mathes, 2014). Other factors may be age, attitude towards risk-taking, memory problems, anxiety and depression, and polypharmacy. Marital status, financial status and income do not appear to be influencing factors for nonadherence (Mathes, 2014). Nonadherence should not be seen as just the patient's problem, but a failure to adequately address the multifactorial reasons for it.

Antibiotics

Antibiotic prescription is common in respiratory disease. Antibiotics are distinct among medications as the more they are used, the less effective they become, leading to bacterial resistance. Nonadherence to antibiotic therapy may lead to therapeutic failure, and reinfection as well. Community antibacterial consumption comprises approximately 85-95% of total antibacterial consumption (Duffy, 2017). In a study by Fernandez in 2014, 243 patients in a community setting were assessed to see if they followed treatment regimens (Fernadez, 2014). 74.5% of the sample were female with a mean age of 46.5 ± 16.6 years. The prevalence of nonadherence was found to be 57.7% and related to delays and failures in taking the prescribed medicine. Factors associated with this were increasing age (OR = 0.97), difficulty in buying the antibiotic (OR 2.34), the duration of treatment (OR =1.28), difficulty with ingestion (OR 3.08), and satisfaction with the information given by physician (OR = 0.33).

Other factors related to nonadherence were the antibiotic, the patient, and the patient-healthcare professional relationship. Fernadez suggests that pharmacists should provide information to patients about the correct use of antibiotics and help to address some of the barriers to adherence (Fernadez, 2014).

It is also found that around one in five antibiotics may be prescribed inappropriately. This may reduce the person's perception of antibiotics as important medications. Researchers from several institutions across the UK, including Imperial College London, and was funded by Public Health England (PHE) (the funders of the research) and the University of Groningen in the Netherlands looked at General Practice (GP) databases in England between 2013-15 to find out how antibiotics were being prescribed (Smith et al, 2018). The researchers asked independent experts to estimate an ‘ideal’ level of appropriate prescriptions of antibiotics in a consultation. They found between 8.8% and 23.1% of all antibiotic prescriptions could be classified as inappropriate, with the highest number of inappropriate prescriptions prescribed for sore throat, cough, sinusitis and ear infections. If we prescribe inappropriately, it raises patient perception that antibiotics will be prescribed.

In their recommendations on prescribing antibiotics, the WHO identified a lack of up-to-date knowledge, inability to identify the infection, patient pressure to prescribe, and financial benefit as affecting prescription rates for antibiotics (WHO, 2003). A further study found patients had multiple expectations of their consultation, with 43% expecting to be prescribed an antibiotic (Courtney et al, 2015).

Assessing the factors associated with nonadherence to antibiotics is important for promoting rational antibiotic use. An interesting piece in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) debated whether we should simplify our antibiotic advice and instead of saying ‘complete’ just say ‘take until better’ (BMJ, 2017). They concluded that due to poor adherence, changes in practice needed to be made.

Inhalers

Nonadherence with inhalers in both asthma and COPD is well documented. A systematic review of 19 studies looked at adherence to inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), the most important treatment for asthma (Barnes and Ulrik, 2015). The mean level of adherence to ICS was found to be between 22% and 63% in the various studies, with improvements up to and after an exacerbation. Poor adherence was associated with milder disease, young people, African-American ethnicity, having <12 years of formal education, and poor communication with the healthcare provider. One of the factors associated with improved adherence was the prescription of a fixed-combination therapy (ICS and long-acting β2 agonists). Good adherence was associated with higher FEV1, a lower percentage of eosinophils in sputum, reduction in hospitalisations, lesser use of oral corticosteroids, and a lower mortality rate. 24% of exacerbations and 60% of asthma-related hospitalisations were due to poor adherence. Some of the studies reported an increase in adherence following focused interventions, which lead to improvements in quality of life, reduced symptoms, increased FEV1, and less oral corticosteroid use (Barnes and Ulrik, 2015). There were two studies reviewed that found no difference in healthcare utilisation, with one reporting no effect on symptoms, and another observing more symptoms in subjects in the intervention group compared with the control group (Barnes and Ulrik, 2015). Interventions to improve adherence showed varying results, with most studies reporting an increase in adherence but, unfortunately, not necessarily an improvement in outcome. Even following successful interventions, adherence remained low (Barnes and Ulrik, 2015).

In COPD, adherence is no different and fewer than half of treatments for COPD are taken as prescribed (Bender, 2014). Most patients abandon their treatment after an initial start, the reasons for which are multifactorial. These can include patients believing there's no benefit in taking the medication, believing it's worsening their condition, or simply an inability to take the medication. This contributes to increased hospitalisation rates, morbidity and mortality and healthcare costs. Depression was found to be a contributing factor (Bender, 2014).

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive disease with a very poor prognosis, but there are two licensed drugs, pirfenidone and nintedanib, which slow the rate of disease progression but appear to have long term intolerability. A study looked at those stopping the medication within the first four weeks of treatment in over 200 patients (Burge et al, 2017). The most common side effects of pirfenidone and nintedanib, photosensitivity and diarrhoea, were not seen to be common reasons for stopping therapies, but gastrointestinal intolerance and disease progression were. They did not find baseline characteristics that defined people who would stop treatment only that those under shared care agreements were more likely to stop and these people, although with they had FEV1, also reported more severe symptoms (385 vs 20% P=0.01) Burge et al (2017) suggest intensive support in the first four weeks of therapy would help adherence rates.

‘Studies have demonstrated that feedback of drug levels and reinforcement for medication intake are effective behavioral measures but may be not practical on a day to day basis.’

Raimundo and colleagues addressed adherence by looking at how many days the medication was prescribed for, and divided the actual dispensing of the medication by the length of follow up, ie what they patient should have received (Raimundo et al, 2017). This was over a two-year period. Discontinuation was defined as a treatment gap of >60 after the medication prescription had run out, and reinitiating treatment was assessed as a restart of the medication after the 60-day period. 34.9% of patients discontinued pirfenidone and 37.5% discontinued nintedanib, and they stayed on treatment 222 days and 183 days respectively. 23.1% of people reinitiated pirfenidone and 12.7% reinitiated nintedanib. While there was no assessment as to why people discontinued treatments, it could be postulated that because the disease has such a poor prognosis there is a stronger adherence to medication (Raimundo et al, 2017). However, Partridge and colleagues found nonadherence rates of between 2-83% in cancer therapies that have a similar poor prognosis, so it is not the whole answer (Partridge et al, 2002).

Do costs affect adherence?

It is often said that the costs of prescriptions affect adherence. However, despite England standing alone amongst the four nations of the UK as not having free prescriptions, adherence is still a problem in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales, suggesting cost is not the only factor. Additionally, 89.9% of prescriptions in England are free at the point of prescription (NHS Digital, 2016).

Other issues

The packaging of medications may affect adherence. Instructions that are difficult to understand, over-complicated inserts and even listing side effects may be off putting. One suggestion to improve adherence is to put the cost of the medication on the packaging. Technology has promise but is expensive. Studies have demonstrated that feedback of drug levels. Reinforcement for medication intake are effective behavioural measures but may be not practical on a day-to-day basis, and self-monitoring of medication or symptoms is so far only a promising methodology (NICE, 2009). Methodological concerns of compliance research are addressed, including setting goals for compliant behaviour, measurement of compliance, and the interpretation of adherence as a correlated and independent factor in outcome. Areas for future research include long-term follow-up, better integration of behavioural theory to treatment development, and better understanding of the compliance and health outcome relationship.

What can we do?

Communicate

Communication is key to helping with adherence. NICE produced guidance on the key principles of communication to improve adherence (NICE, 2009):

- Adapting consultation styles to the needs of individual patients, so that all patients have the opportunity to be involved in decisions about their medicines at the level they wish

- Establishing the most effective way of communicating with each patient and, if necessary, considering ways of making information accessible and understandable (for example, using pictures, symbols, large print, different languages, an interpreter or a patient advocate)

- Offering all patients the opportunity to be involved in making decisions about prescribed medicines and establishing what level of involvement in decision-making the patient would like

- Being aware that increasing patient involvement may mean the patient decides not to take or to stop taking a medicine. If in the healthcare professional's view this could have an adverse effect, then the information provided to the patient on risks and benefits and the patient's decision should be recorded

- Accepting that the patient has the right to decide not to take a medicine, as long as the patient has the capacity to make an informed decision and has been provided with the information needed to make such a decision

- Being aware that patient's concerns about medicines, and whether they believe they need them, affect how and whether they take their prescribed medicines

- Offering information relevant to the condition, possible treatments and personal circumstances, and that is easy to understand and free from jargon

- Recognising that nonadherence is common and that most patients are nonadherent sometimes

- Routinely assessing adherence in a non-judgmental way whenever prescribing, dispensing and reviewing medicines (NICE, 2009).

We should also use every opportunity to optimize medication use. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) produced a guide on medicines optimisation to help patient's make the most of their medicines (RPS, 2013). This guide suggests four guiding principles for medicines optimisation, aiming to lead to improved patient outcomes:

- Aim to understand the patient's experience

- Evidence-based choice of medicines

- Ensure medicines use is as safe as possible

- Make medicines optimisation part of routine practice

Conclusion

By looking at various respiratory diseases it is evident that nonadherence is common across several disease processes, these issues need to be addressed. In addressing adherence, consideration must be taken before prescribing, and the shortest recommended regimens for what is being treated should be prescribed. Prescirbers should be adaptable to the pressures of prescribing, especially when dealing with antibiotics, and be able to handle discussions around this. Communication is vital in order to understand the patients prescribing needs, as well as understanding their ideas, concerns and expectations. Efforts should be made to maintain simplicity, the fewer medications the better, leading to less potential for confusion. Medications should be reviewed if adherence is not followed. Finally, follow the advice of the police (to whom this is attributed) and keep it to ABC Assume nothing, Believe nobody, Check everything and accept that no one is perfect and 100% adherence is unlikely especially over time, but aim for the next best thing.

Key Points

- Around half of people do not take their medications as prescribed

- Many prescriptions are given out for respiratory disorders, but many are not taken correctly

- People do not always follow treatment regimens

- Adherence may be intentional or nonintentional

- There are many barriers to adherence

- Communication and understanding is key to promoting adherence

CPD reflective questions

- Considering adherence, what do you think are the most important issues for us to address when we are prescribing?

- When we are reviewing patients, how can we raise the matter of adherence without losing our therapeutic relationship?

- Reflecting on your last five patients you have prescribed for whom would you think likely to be the most adherent and why?

- Reflecting on your last five patients you have prescribed for whom would you think likely to be the most nonadherent and why?

- Have you ever not followed a prescribed course of treatment and why?