Postoperative pain is a continuing problem (Chanif et al, 2012). More than 80% of patients complain of pain during the immediate postoperative period, with 75% rating it as moderate, severe or extreme. Additionally, evidence indicates that less than half of patients experience adequate pain management (Chou et al, 2016).

Acute postoperative pain begins with surgical trauma, tapers off gradually and ends with tissue recovery (Topcu and Findik, 2012). Abdominal surgery is recognised as a particularly painful procedure. Pain is caused by ischaemia and the release of neuropeptides at the trauma site and throughout the nervous system, due to the site’s proximity to the diaphragm and cross-innervations in the abdominal area. Pain is an unavoidable side effect of all major abdominal operations (Rejeh et al, 2013; Watkins et al, 2014; Nurhayati et al, 2019).

According to the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) programme, adequate pain relief after surgery is strongly recommended to enhance early mobilisation, decrease the risk of developing postoperative complications, shorten the length of hospital stay and reduce morbidity rates (Gustafsson et al, 2019). Conversely, inadequate pain management after abdominal surgery increases the risk of delayed mobilisation and wound healing, developing venous thromboembolism and systemic infection. Acute pain services are central to providing pain management for patients undergoing surgery, and nurses and anaesthesiologists are acknowledged to perform a vital role (Borracci et al, 2016; Severgnini et al, 2013).

Nursing intervention

In Songklanagarind Hospital, Thailand, pain management after surgery was the responsibility of the acute pain service. To achieve optimal outcome for patients and maximise the quality of pain management, the service launched a nursing-care programme. This would use a combination of pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapy to reduce pain intensity, alongside several other facets, including:

- Providing preoperative information

- Encouraging patient participation in decision-making

- Measuring patient satisfaction (Gordon, 2010).

Evidence-based practice was reviewed to develop innovative nursing care for acute pain management after abdominal surgery. The nursing care programme was presented to the nurses in the surgical ward and surgical intensive care unit before implementation, to adjust the feasibility of the programme in the clinical context.

Interventions to manage acute pain were divided into pre- and postoperative periods. Preoperative management included taking the patient’s history, assessing their pain and educating them to assess their own pain and set pain-management goals. Postoperative management included assessing pain, managing it with pharmacological and non-pharmacologicaltreatments and preparing the patient for discharge (Box 1).

Box 1.Nursing interventions for acute pain after abdominal surgeryPreoperative

- Educate patient and caregiver about postoperative pain treatment, and set a goal regarding pain management (pain score at rest < 3/10, and pain score during activity < 4/10)

- Educate the patient on how pain is reported and assessed by using pain assessment tools (VAS, NRS)

- Assess any underlying misconceptions about pain and analgesics

- Take history, such as previous experiences with surgery and postoperative treatment, medication allergies and drug use

- Educate the patient regarding risk factors that influence pain assessment and management, such as previous surgery and postoperative treatment, medication allergies and cognitive status

- If the treatment does not achieve the goal, recommend that the patient receive another non-pharmacological pain treatment

Postoperative

- Assess factors that may influence the intensity, location and extent of the pain

- Assess factors that may influence pain assessment results, such as developmental status, cognitive status, level of consciousness, educational level and cultural and language differences

- Assess previous treatments and any associated side effects

- Assess pain intensity using appropriate tools (VAS, NRS, VRS and symbols)

- For pharmacological treatment, assess pain intensity 15–30 minutes after parenteral therapy and 1–2 hours after administration of an oral analgesic

- Following recommendations, relieve pain intensity with multimodal therapies, such as epidural and PCA, with morphine and fentanyl as the first- and second-line drugs, respectively

- Assess the appropriateness and adequacy of pain prescription and discuss with medical doctor if inappropriate or inadequate

- For non-pharmacological treatment, assess pain intensity at four timepoints: before intervention and 15 minutes, 6 hours and 12 hours after treatment

- Following recommendations, use physical modalities for pain therapy, such as massage and cold therapy, and for other treatments use cognitive–behavioural modalities, such as meditation, imagery, relaxation and music therapy

- Reassess pain every 4 hours

- If pain treatment goal not achieved, provide access to consultation with a pain specialist regarding pharmacological therapy for controlling postoperative pain

- Provide education and instructions on tapering opioids to target dose after discharge

Note: VAS: visual analogue scale; NRS: numeric rating scale; VRS: verbal rating scale

Aim

A study was undertaken to describe the implementation of an acute pain management programme in clinical practice and provide an in-depth understanding of the nature of pain experienced by patients in the service, as well as evidence that could be used to guide improvements in pain management.

Method

This nursing-care programme was implemented in the surgical ward and surgical intensive care unit of Songklanagarind Hospital. The participants were willing adults over the age of 18, who were undergoing abdominal surgery and had no problems with communication. Patients and their caregivers were informed about the purpose, activity and plan for the study. Permission from patients and caregivers was obtained before the procedure, and data were recorded confidentially.

A multidimensional assessment tool was created to collect data for the variables given in Box 2. Patient perceptions of pain intensity were assessed using a scale of 0-10, with 0-3 indicating low-, 4-6 indicating medium- and 7-10 indicating high-intensity pain. Clinicians compared this data with an assessment of any provocative factors for the pain; the quality of the pain, and the pain’s impact on activity, sleep and emotional state.

Box 2.Data collection

- Medical history (surgical, analgesic and substance use)

- Demographic information (age, gender)

- Surgical situation (type of operation and presence of comorbidities)

- Pharmacological interventions used by postoperative day

- Administration route of pharmacological interventions

- Side effects of pharmacological interventions

- Non-pharmacological interventions used by postoperative day

- Patient satisfaction with treatment and preoperative information

- Reported intensity of pain at rest and during physical activity

Results

Demographics

Nine patients, aged 34-76 years and 78% male, who met the inclusion criteria were enrolled (Table 1). More than half of the patients had a history of surgery and previous pain. Most patients had laparotomies, while two received minimally invasive surgery. All patients reported participating in pain decision-making and satisfaction with the usefulness of the preoperative information.

Table 1. Patient characteristics (n=9)

| Demographics | History | Surgical situation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Age | Gender | Surgical | Analgesic | Substance use | Type of operation | Comorbidity |

| 1 | 73 | Male | Laparotomy | Yes | – | Cholecystectomy | Yes |

| 2 | 53 | Male | ORIF | Yes | – | Laparoscopic ULAR with protective ileostomy | No |

| 3 | 53 | Male | – | No | Alcohol, smoking | Simple closure with omental patch and liver S3 biopsy | No |

| 4 | 63 | Female | – | No | – | Pylorus-resecting pancreaticoduodenectomy | Yes |

| 5 | 61 | Male | Hepatectomy | Yes | Smoking | Wedge liver resections S3 with RFA S2/3 with repair hernia with ileostomy closure | Yes |

| 6 | 55 | Male | Appendectomy | Yes | – | Pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy | No |

| 7 | 76 | Male | – | No | Alcohol, smoking | Anterior resection | No |

| 8 | 58 | Male | – | No | – | OGD with biopsy and laparotomy gastrotomy | Yes |

| 9 | 34 | Female | Caesarean | Yes | – | Laparoscopic liver biopsy | No |

Notes: OGD=oesophagogastroduodenoscopy; ORIF=open reduction and internal fixation; RFA=radiofrequency ablation; ULAR=ultra-low anterior resection

Reported pain

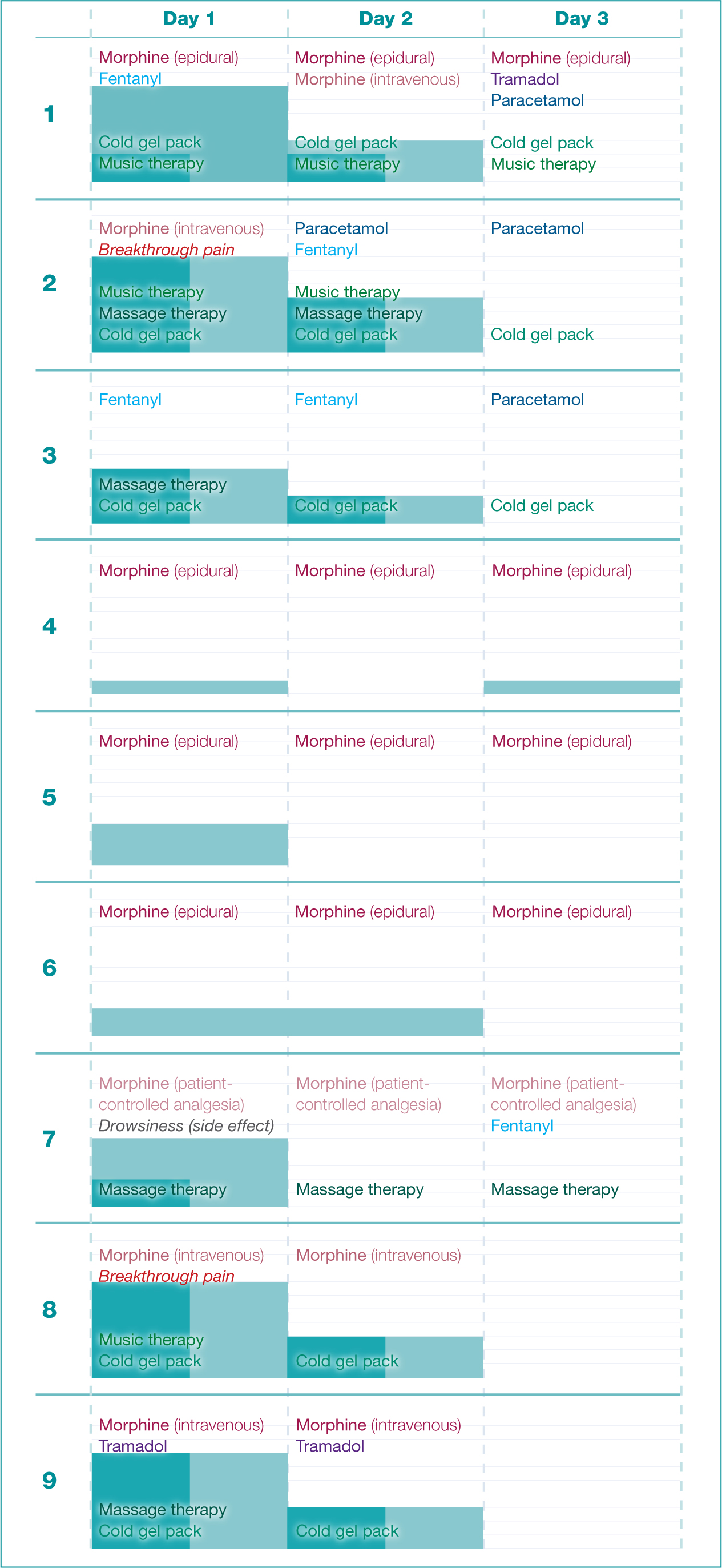

Patients described their pain over 3 postoperative days (Figure 1). The pain sensations were described as stretching (six patients) and throbbing (three patients), with a duration of less than 5 minutes for each experience. Two patients experienced breakthrough pain, which refers to pain that occurs at any time during the day and increases to a high intensity very rapidly within 30-45 minutes after pharmacological administration. Sitting and moving were reported as provocative factors during the first and second post-surgical days. Pain had the most impact on activity and sleep during the first post-surgical day.

The intensity of pain was reported on a 0-10 scale, and different values were reported when patients were at rest or engaging in physical activity. Pain at rest was reported by six (67%) patients on the first day, five (56%) on the second and none (0%) on the third. For five of six the (83%) affected patients, pain at rest decreased in intensity from the first to the second day.

Pain on activity was reported by all nine patients (100%) on the first day, six (67%) on the second and only one (11%) on the third. This pain decreased over time in all but two cases, one persisting at level 3 from the first to the second day and the other falling from 1 on the first day to 0 on the second and rising back to 1 on the third. Pain on activity was usually more severe than at rest, although sometimes it was the same.

All patients achieved the goal of pain relief where pain at rest was less than 3 and during activity was less than 4. All participants reported satisfaction with the pain treatment.

Analgesic interventions

Patients were prescribed a variety of pharmacological analgesics, including the opioids morphine (89%), fentanyl (33%) and tramadol (22%), as well as paracetamol (33%). The dosage and number of patients treated per day with each medication are given in Table 2. Pain management was most frequently delivered intravenously, less frequently by epidural analgesia and least frequently by patient-controlled analgesia (Table 3).

Table 2. Pharmacological analgesic interventions (n=9)

| Drug | Dose | Total | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morphine | 30 mg intravenously every 3 hours | 8 | 8 | 7 | 5 |

| Fentanyl | 30 μg intravenously every 3 hours | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Tramadol | 50 mg orally every 6 hours | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Paracetamol | 500 mg orally every 6 hours | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

Table 3. Pharmacological administration route (n=9)

| Route | Total | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intravenous (morphine and fentanyl) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 |

| Epidural (morphine with bupivacaine) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Patient-controlled analgesia (morphine) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Oral (paracetemol and tramadol) | – | 1 | 2 | 3 |

A single patient developed a recognised side effect of pain medication. The patient reported drowsiness after receiving patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) with morphine alone. Non-pharmacological therapy used as an adjunct to multimodal pharmacological analgesia included cold gel packs (56%), massage therapy (33%) and music therapy (23%) (Table 4).

Table 4. Non-pharmacological analgesic interventions (n=9)

| Therapy | Total | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cold gel pack | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 |

| Massage therapy | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Music therapy | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

The majority of patients used non-pharmacological therapy, and six (67%) reported its effectiveness. Of the three (33%) who did not use non-pharmacological methods, two were unwilling to use the recommended strategies, and one was dissatisfied with the cold gel pack, describing increased pain intensity on use.

Discussion

Acute pain after surgery is commonly nociceptive (as opposed to neuropathic), and it is often characterised as aching, throbbing, shooting, stretching, sharp, tender, burning, and penetrating (Gordon et al, 2016). The high prevalence of acute pain after abdominal surgery is in line with other studies; Chanif et al (2012) reported 74% acute pain prevelance. The results also underline how this pain is high in intensity during the immediate post-surgery period and increases with physical movement, such as the act of sitting. This increase is likely to be the result of muscle contraction and nerve swelling in the incision wound during activity (Gordon et al, 2016).

Seven (78%) patients received laparotomies, characterised by a large abdominal incision, while two (22%) received minimally invasive surgery, defined as an operation performed using small incisions (usually 0.5-1.5 cm). The latter are usually associated with shorter recovery times, and thus reduced postoperative pain. However, both patients who had minimally invasive surgery reported high-intensity postoperative pain. This may have been influenced by their intraoperative position, the location of their incisional wound (in the lower abdomen) and/or CO2 persisting for more than 48 hours in the subdiaphragmatic space following the laparoscopic procedure (Chou et al, 2016). In addition, in one of these cases the pain may have been caused by pressure on the incision wound from the colostomy appliance; consequently, the position of the colostomy bag was changed and an alternative wound dressing was used.

As a method for delivering pharmacological pain management, epidural analgesia was used in only three (33%) patients, which was less frequent than intravenous delivery and reflective of its limited use in this setting. However, epidural analgesia has been reported to be highly effective and is recommended for pain management after abdominal and thoracic surgery (Schug et al, 2015). This is supported by the finding that, of the three treated with epidural analgesia, two reported no pain during both rest and activity on all three postoperative days. However, the third person did report high pain intensity of 7/10 on day 1, but it was discovered that the initial epidural needle size and placement was inadequate. Once rectified, the patient’s pain score decreased significantly to 4/10 on day 2.

The opioids morphine and fentanyl are the first- and the second-line drugs prescribed for pain relief following abdominal surgery (Hughes, 2014). In this study, patients received morphine 30 mg and fentanyl 30 µg. According to Pezzala et al (2017), there is no maximum dosage for morphine, but the upper limit is 2-3 mg/kg/h, while the optimal dosage for fentanyl is 50-100 µg. The majority of patients in our study received adequate pain medication.

The only study participant to have any side effects from the pain medications experienced drowsiness while using PCA. PCA is a method of pain control that gives the patients the power to control their pain via an intravenous delivery pump (Chou et al, 2016). However, this patient had an incomplete understanding of how to use the device, which was compounded by an incorrect PCA history and phlebitis around the PCA site that resulted in ineffective PCA delivery.

The results of this study supported non-pharmacological pain management through patient preference. Patients participated in decision-making in actively choosing non-pharmacological therapy (music, massage and cold gel packs), and the process was not nurse-led. In this study, each patient achieved the goal of pain management and reached the defined outcomes of pain at rest less than 3/10 and during activity less than 4/10.

Conclusion

This study has underlined the importance of the right professional skills and education. The anaesthetist should have advanced skills for accurate epidural placement, and nurses should be trained to assess the effectiveness of epidural administration. Nurses should be trained in the use of PCA administration, as well as recording and analysing demand and delivery of analgesia.

Non-pharmacological therapy was effective as an adjunct to pharmacological therapy, and these methods should be employed based on patients’ preferences. All of the patients had adequate pain relief and achieved the management goals. Nurses are recommended to record pain intensity, both at rest and activity. Based on evidence-based nursing interventions, epidural analgesia is highly recommended for the relief of pain in patients undergoing abdominal surgery.

Key Points

- Using a mix of pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods was effective in treating acute pain after abdominal surgery

- Pain management administration was either intravenous, epidural or via patient-controlled analgesia

- Nurses should be trained in the recording and delivery of analgesia, alongside PCA administration

CPD reflective questions

- What is the most sensitive and accurate pain assessment tool to assess postoperative pain in the acute phase?

- What is the most effective pharmacological therapy to manage acute pain after abdominal surgery, and why?

- What is the most effective non-pharmacological method to manage acute pain after abdominal surgery?