Lymphoedema is a debilitating, enduring condition connected with several diseases including cancer. It is characterised by atypical swelling lasting for more than 3 months and can occur in any part of the body. Those affected may experience skin changes, pain, heaviness, recurrent cellulitis, reduced mobility and psychological distress (Morgan et al, 2005; Greene and Meskell, 2016; Thomas et al, 2020). Evidence suggests that the impact of Lymphoedema on an individual’s health, wellbeing, sense of self and quality of life may be profound (Thomas et al, 2020; Greene and Meskell, 2016). As a chronic condition, lymphoedema can have a significant impact on health outcomes and results in a substantial burden to the NHS (Atkin, 2016; Moffatt et al, 2016; Guest et al, 2016; Thomas et al, 2017). Lymphoedema requires ongoing management including skincare, exercise and the daily use of compression garments (Lymphoedema Framework, 2006). Since 2007, compression garments have been accessed through Part 1XA of the drug tariff in the UK, which covers appliances (NHS Business Services Authority, 2021a). Ineffective management of the prescription process alongside inappropriate prescribing of garments have been identified by patients and healthcare professionals as important issues.

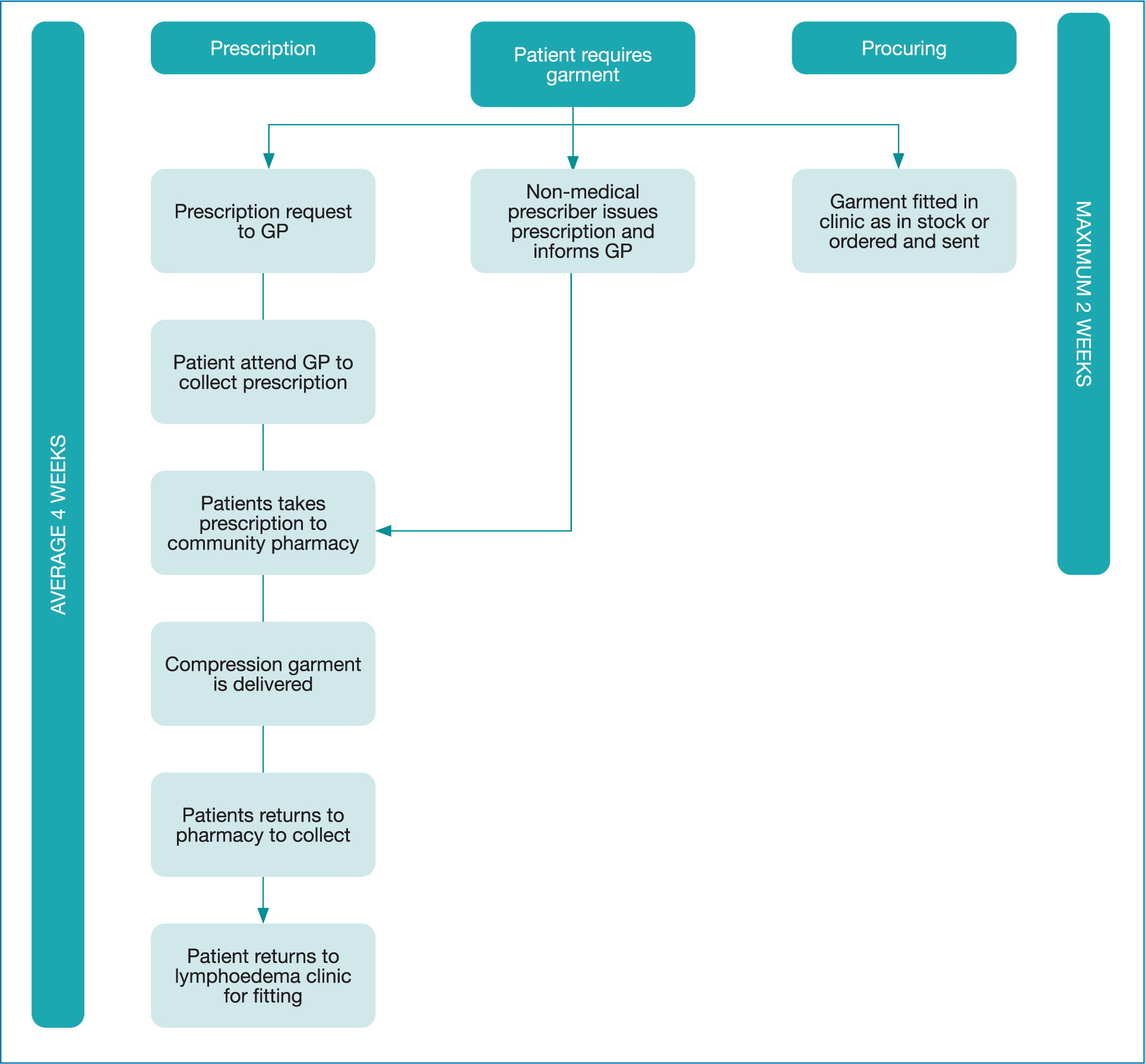

Throughout Wales and in the UK, many patients’ access compression garments via a prescription that is completed by the general practitioners (GPs) based on a request from a lymphoedema professional (Woods, 2018). This prescription process has many unnecessary steps, which does not focus on quality of care, safety, and is not a patient-centred experience. These superfluous steps include writing prescriptions or referral to GPs for prescriptions, collecting and taking prescriptions to community pharmacists (CPs), and returning to collect the prescribed compression garment and lastly, for 80% of patients, they have to return to the lymphoedema service for a fitting appointment. The processes on average takes 4 weeks, but some are delayed for over six, resulting in treatment delays. Further, when the garment is wrongly dispensed, the process begins again (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Prescription versus procuring patient pathway

Figure 1. Prescription versus procuring patient pathway

As the incidence and prevalence of lymphoedema increases because of improved awareness so does the annual demand for lymphoedema compression garments accessed from the NHS drug tariff. During the last 6 months compression garment prescriptions fulfilled in the UK amount to nearly £20 million from the NHS drug tariff with a potential spend of over £40 million per annum and is still growing exponentially.

Unfortunately, waste, harm and variation in garments being prescribed via NHS prescription forms have been identified nationally (Board and Anderson, 2018; Woods, 2018). Incorrect dispensing of garments occurs frequently and has even caused harm in patients being issued with the wrong sizes and style of garments exacerbating their oedema (Woods, 2018). The delays and errors in garments being dispensed have negatively affected patient outcomes by preventing prompt treatment and impacts on compliance. Moreover, the lymphoedema services receive numerous phone calls from patients, GPs, prescription clerks and CPs regarding the garment prescription requests because of confusion over the wide variation (tens of thousands of compression garment lines on the drug tariff due to numerous sizes, colours and designs) (NHS Business Services Authority, 2021b).

In addition to prescriptions, compression garments are also procured via secondary care and these costs are also mounting. In 2014, NHS Wales Shared Services and Lymphoedema Network Wales (LNW) completed an all wales lymphoedema compression garment contract (Thomas and Morgan, 2017)ensuring best garment, best price and best outcomes. The contract was developed following collaboration with lymphoedema clinicians, stakeholders, surgical material testing laboratory and NHS Wales shared services. This contract guarantees that patients receive the best product (as it has been tested) for the best price from a procurement perspective. Subsequently, the All Wales Lymphoedema Compression Garment Formulary was created in 2015 for primary and secondary care and renewed again in 2018. The formulary was rolled out nationally and provides evidence-based compression information for all professionals. The current expenditure in NHS Wales for procuring compression garments is in excess of £1.4 million per annum.

Following value-based healthcare principles (Gray, 2017) it transpired that many lymphoedema compression garments cost much less to procure in secondary care than the drug tariff reimbursement charge. However, it is important to note that the funding route of the NHS is different in each of the four nations in the UK. As NHS Wales is a devolved nation, all NHS funding involves primary and secondary care. In England, the Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) are responsible for all funding thus the change in process could be targeted at a local level.

To clarify the pricing differences, it is essential to understand that there are two types of compression garments. Flat knit garments are manufactured flat and then sewn together with a seam. They are used for patients who have skin folds, skin conditions and complicated oedema. A circular knit garment is made on a spherical knitted machine and has no seams. It is mainly used for mild/moderate oedema (Lyhmphodema Framework, 2006). Compression garments can also be categorised into ready to wear or made to measure and the costs of these garments are all different. For example, lymphoedema circular compression tights are around £48 on the drug tariff and £26 when procured directly. A thigh circular knit compression garment is around £54 on drugs tariff and is £25 cheaper when procured. Flat knit garments are not available ready to wear on the drugs tariff thus the only way to access would be via a made to measure, which introduces significant additional costs of around £30 per garment including VAT (NHS Business Services Authority, no date. Thus, if compression garments were procured directly instead of being accessed via the drugs tariff, opportunities for cost savings could be available.

Subsequently, an alternative process was considered adhering to value-based healthcare principles ensuring that resources used are sustainable and achieve better outcomes and experiences for patients. Accordingly, LNW, GPs, CPs and medicine management staff agreed to pilot an alternative process so that lymphoedema services could procure lymphoedema garments direct from the pharmacy budget, removing the need for GPs and CPs, thereby reducing the need for prescriptions. This article will present the data on the changed process and discuss the permanent service redesign that could be replicated.

Aims and objectives

The main aim of this evaluation was to estimate the potential impact of changing the way compression garments are accessed from a prescription to a procurement process. The main objectives were to:

- Estimate the costs of the service redesign

- Investigate any delays in patients receiving compression garments.

Methods

Ready to wear compression garment stock was purchased at a cost of £15 000 in each of the two piloted services. The stock was based on the high usage of different types of garments across these services and included a variety of commonly used sizes and styles. If a made to measure garment was required, then this was ordered following the same procuring process. A data form was devised by the team so that information was collected by lymphoedema therapists for each compression garment issued to patients attending the twoservices in Wales over 12 months. The data collection included details on the garment ordered: the costs if prescribed (based on drug tariff) compared to procured (based on NHS contract), the date the garment was ordered and received and a comparison of the processes.

There were slight differences within the two lymphoedema services undergoing the service evaluation, as service A had two non-medical prescribers who wrote the prescriptions for patients and service B requests that GPs issue prescriptions. Team meetings were held with all staff so all were aware of the new process and service evaluation. All non-patient identifiable data from the form was emailed to a project manager and entered into a Microsoft Excel database. All data were checked and costings verified by two of the authors. Any missing data was presumed to be zero resource usage. Analysis was undertaken in Microsoft Excel and SPSS Version 22 for Windows to identify any correlations and descriptive counts between the variables collected. This study design was ratified as service evaluation by the local Joint Service Research Committee and no formal NHS ethics permissions were required to conduct the evaluation. Swansea University College of Human and Health Sciences (CHHS) ethics committee also deemed the study a service evaluation for a senior researcher (IH) to analyse the anonymised datasets.

Results

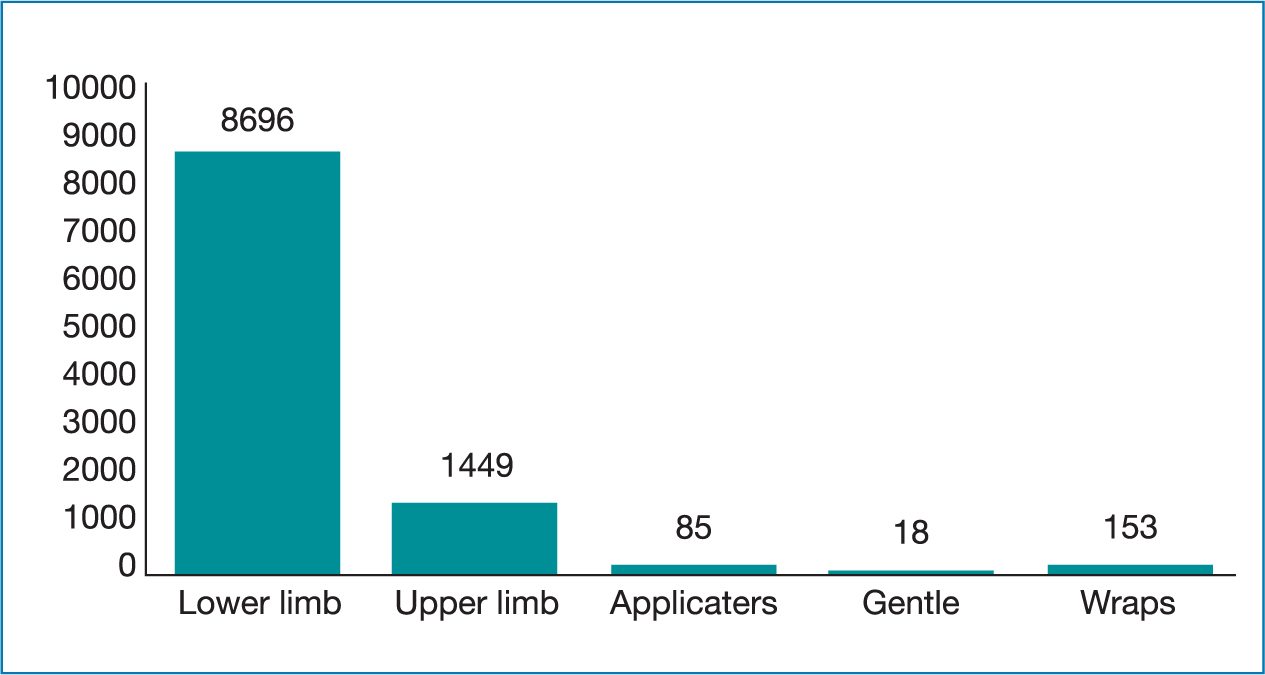

For this study, 5392 forms were completed on patients receiving compression garments from the two lymphoedema services over 12 months (3432 patients (64%) from service A and 1960 patients (36%) from service B). Across both services, 957 (18%) were new patients, compared to 4435 (82%) who were follow up patients. Of the 5392 patient data forms, this equated to a total of 10 401 compression garments (an average of two garments per patient). A large proportion of the garments ordered were for lower limb lymphoedema (84%) followed by upper limb (14%) and miscellaneous items, as highlighted in Figure 2. Of the garments required, 4915 (47%) were flat knitted and 5128 (49%) were circular knit. Positively, 95% (9881) of the garments requested (ready to wear and made to measure) were part of the NHS Wales compression garment contract compared to 520 (5%) being non-contracted items.

Figure 2. Types and numbers of compression prescribed

Figure 2. Types and numbers of compression prescribed

Over half of the garments issued (52%) were fitted on the day of the appointment as they were in stock; 7% were ordered as the patient required made to measure garments and 41% were ordered although they were ready to wear the product but were not available in the service. Of the patients (2578) requiring garments that were ordered, 1283 (50%) were collected; 834 (32%) were posted by the lymphoedema service direct and 461 (18%) required an additional appointment at the lymphoedema service as the garment had to be fitted. In contrast, no patients were fitted on the same day when accessing garments via the prescription route.

Reviewing the new and follow-up patients, more new patients (71%) were fitted with garments on their appointment than follow-up patients (48%) as highlighted in Table 1. Data showed that even though 2230 patients could have been fitted with a garment at the time of their appointment they were not in stock and 16% (346) had to have an additional appointment for a fitting (Table 2). Compared to the prescription route, 80% required a return to the service for fitting.

Table 1. Cross tabulation between new/follow up patients by fitted/ordered

| Garment fitted at appointment or ordered? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New patient or follow up | Fitted ready to wear | Ordered made to measure | Ordered ready to wear | Total |

| New patient | 683 (71%) | 30 (3%) | 244 (26%) | 957 |

| Follow up | 2131 (48%) | 318 (7%) | 1986 (45%) | 4435 |

Table 2. Cross tabulation between collected, fitted or posted and ready to wear

| Was the garment fitted at the appointment or ordered compared with ordered m2m or ready to wear? | ||

|---|---|---|

| How was the garment delivered? | Ordered made to measure | Ordered ready to wear |

| Collected | 112 (32%) | 1171 (52%) |

| Fitted | 115 (33%) | 346 (16%) |

| Posted | 121 (35%) | 713 (32%) |

| Total | 348 | 2230 |

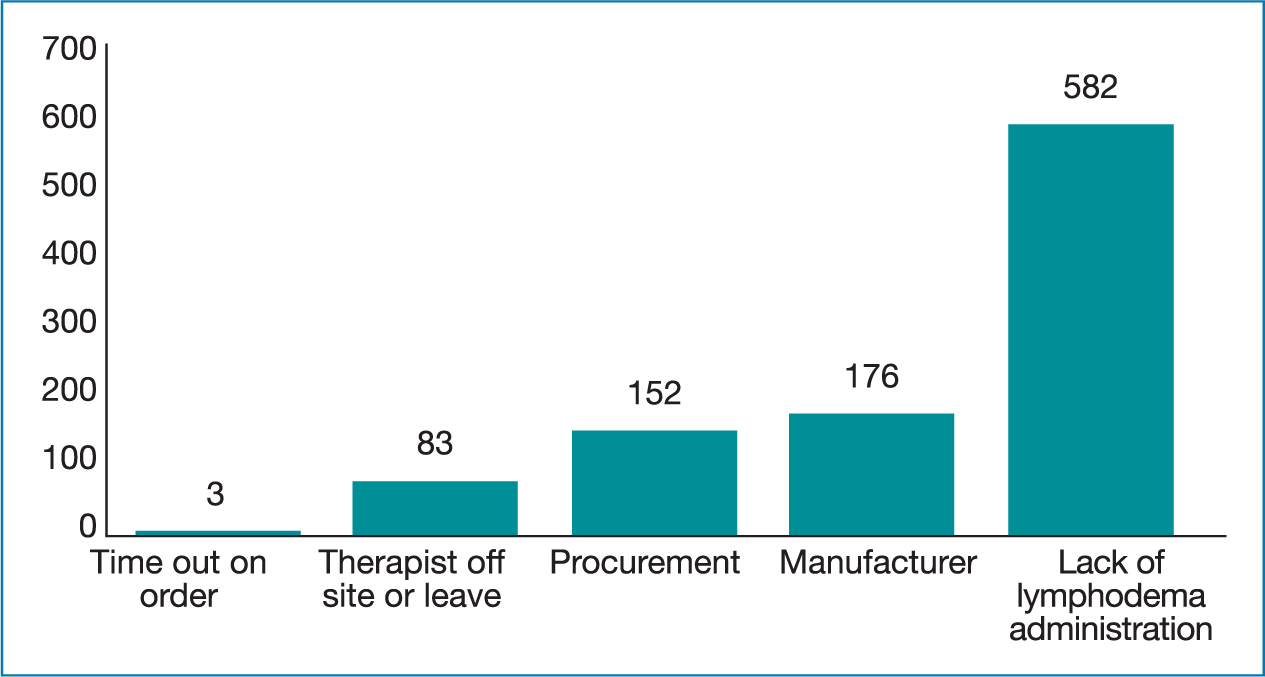

Data were also collected on the procuring time delays (more than 11 working days as within the contract is a 10 day turnaround) if garments had to be ordered which amounted to 996 out of 2578 (39%). As reported in Figure 3, the main reasons for the delays were a lack of administrators in the lymphoedema clinic followed by manufacturing delays (making/distributing) and procurement (awaiting a price if noncontract/manpower). Table 3 details the analysis of the time lag between different garments ordered. Made to measure garments had the highest time lag with an average of 14 days, compared to 10 days for ordered ready to wear. Further, it transpires that non-contracted items take on average 12 days to arrive compared to 7 days for contracted items.

Figure 3. Delays in receiving garments

Figure 3. Delays in receiving garments

Table 3. Time lags between ordered garments (made to measure and ready to wear)

| Time lag between appointment and item requested (days) | Time lag between appointment and item ordered (days) | Time lag between appointment to date dispatched (days) | Time lag between appointment to date received (days) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collected | Mean | 0.4 | 3 | 11 | 14 |

| Fitted | Number | 348 | 348 | 348 | 348 |

| Posted | Sum | 160 | 1080 | 3812 | 4729 |

| Total | Mean | 1 | 3 | 6 | 10 |

| Number | 2230 | 2230 | 2230 | 2230 | |

| Sum | 2222 | 6571 | 13 478 | 22 475 |

Comparing the costs of prescribing versus procuring garments

The staffing costs associated with prescribing garments were estimated for lymphoedema service A and B. As previously described, service B uses GPs for issuing prescriptions and service A has non-medical prescribers, which therefore bypasses the need for GP involvement. For service A, the staffing element of prescribing a garment was estimated as £37 (Table 4) and for service B, this was projected to be £57 as it includes GPs (Table 5). Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) and Agenda for Change NHS costs were used for calculations of staffing costs (Curtis and Burns, 2020; NHS Employers, 2021). In calculating the costs for the procurement process, a new Band 3 Garment Administrator would be employed to order, restock, send and provide patients with garments, which would be at a cost of £1.80 per patient (Table 6). The difference in staffing costs indicates that using the prescribing process is overwhelmingly more costly than using procurement (Table 7). Total costs across the two lymphoedema services for staffing only (n=5392) show a mean per-patient cost of £106 (SD £74) for prescription process and £77 (SD £54) for the procuring process (including the band 3 administrator).

Table 4. Costs to Service A for Prescribing process

| Cost items | Unit cost source/description | Cost per task | Total cost based on 3432 patients | Task |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare practitioner (Band 7) | PSSRU (Curtis and Buns, 2020)Band 7 (15 minutes) | £14.50 | £49 764 | Writing script |

| Community pharmacist (Band 6) | PSSRU (Curtis and Buns, 2020)Band 6 (30 minutes) | £22.50 | £77 220 | Ordering, processing order, telephone queries and invoicing checking order/receipting with patients |

| £126 984 | £37 per patient |

Table 5. Costs to Service B for prescribing process

| Cost items | Unit cost source/description | Cost per task | Total cost based on 1960 patients | Task |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lymph specialist (Band 6) | PSSRU (Curtis and Burns, 2020) Band 6 (30 minutes) | £22.50 | £44 100 | Completing Prescription Request form/sending to GP with letter for a prescription |

| General practitioner | PSSRU (Curtis and Burns, 2020) General Practitioner (10 minutes) | £7.30 | £14 308 | Signing scripts - (actual cost per GP prescription) |

| Prescription clerk (Band 2) | https://www.nhsemployers.org/pay-pensions-and-reward/nhs-terms-and-conditions-of-service---agenda-for-change/pay-scales/hourly (30 minutes) | £4.95 | £9 692 | Writing, searching for items, telephone queries |

| Community Pharmacist (Band 6) | PSSRU (Curtis and Burns, 2020)Band 6 (30 minutes) | £22.50 | £44 100 | Ordering, processing order, telephone queries and invoicing checking order/receipting with patients |

| £112 200 | £57 per patient |

Table 6. Proposed costs if the service redesign was implemented

| Cost Items | Unit cost source/description | Cost per task | Total cost | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Band 3 | https://www.nhsemployers.org/pay-pensions-and-reward/nhs-terms-and-conditions-of-service---agenda-for-change/pay-scales/hourly | £1.81 | £9759 | Every patient for the ordering process - 10 minutes (based on 5,392 Patients) |

| Cost per oracle | £9759 | £1.80 |

Table 7. Summary of costs comparing the two processes

| Item n= 5392 | Total cost of garments across both services | Mean cost per patient | Standard deviation | 95% xonfidence interval of the difference | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procuring cost of garments | £344 943 | £33.70 | £45.10 | £64 (£62.8, £65.2) | <0.001 |

| Procuring cost including VAT | £413 932 | £40.40 | £54.10 | £76.8 (£75.3, £78.2) | <0.001 |

| Prescribing cost of garments | £553 259 | £54.00 | £71.80 | £102.60 (£100.7, £104.5) | <0.001 |

| Prescribing cost including dispensing charge | £569 540 | £55.60 | £74.00 | £105.6 (£103.7, £107.6) | <0.001 |

| Overall costs procuring route | £424 716 | £41.50 | £54.10 | £78.80 (£77.3, £80.2) | <0.001 |

| Overall costs prescribing route | £808 244 | £78.90 | £74.90 | £149.90 (£147.9, £151.9 | <0.001 |

| Overall difference in costs | -£383 528 | -£37.40 | £40.8 | -£71.10 (-£72.2, -£70) | <0.001 |

Analysing the costs of the compression garment highlights that procuring is far more economical than prescribing (Table 7). Procuring garments suggests an average per patient cost of £40.40 compared to £55.60 for prescribing. When the costs include the garments and staffing, a mean per-patient cost of £149.90 (SD £75) for the prescription process and £78.80 (SD £54) for the procuring process. The difference in overall costs is then estimated at -£71.1 (SD £40.8) and this difference is also seen as statistically significant (P-value <0.001).

A one-way sensitivity analysis (±30%) was undertaken (Table 8) to assess the extent of altering the main cost parameters on the cost of the impact of the service evaluation. This indicated that the results remained consistent and in favour of altering the process from prescription led to a procuring service redesign.

Table 8. Results of one-way sensitivity analysis

| Parameter | Base-case (mean) | Lower range (mean) | Upper range (mean) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall costs prescribing | £149.90 | £104.93 | £194.87 | In favour of altering process and a service redesign |

| Overall costs procuring | £78.80 | £55.16 | £102.44 | |

| Overall difference in costs | -£71.10 | -£49.77 | -£92.43 |

Limitations

A limitation of this study is the narrow perspective adopted on direct NHS costs through PSSRU and Agenda for Change (Curtis and Burns, 2020). As a result of the available resources, it was not possible to include the indirect costs relating to the prescription route for patients for example travelling, time off work. The authors were also unable to estimate the costs incurred with the procuring process. Although pragmatically a reduced impact seems logical as the need for patients to travel to collect prescriptions from their GP, take to pharmacy and collect is eliminated. Postal prescription service is not used within lymphoedema services in Wales, however, this approach along with direct ordering with their local pharmacy could have sped up the process. If the journey on average was 10.8 miles for each patient (Iredale et al, 2013) (5392), there is a reduction for substantial out of pocket expenses. Only the costs associated to the ordering of garments were reviewed and did not include the costs associated with additional fitting appointments or postal charges for the prescription or procuring route. Another limitation may be that not all data forms were completed by therapists, although 5392 is a positive number of returns. Lastly, this first attempt at costing the prescription route for compression garments does not include a patient’s qualitative perspective. This requires a further study to establish if the change in the process does indeed impact the patient experiences of obtaining compression garments.

Discussion

This analysis of 5392 patients across two lymphoedema services indicates there are differences between the timing and quality of care the patients receive comparing the prescription to procuring route. Comparable to other research (Board and Anderson, 2018; Woods, 2018) waiting unacceptable lengths of time for compression garments affect care and concordance to treatment.

Furthermore, the risk of error with the additional steps in prescribing will likely further impact concordance and patient outcomes. The amount of time waiting for a garment via the prescription route is on average 4 weeks (Board and Anderson, 2018; Woods, 2018). Other solutions such as the postal prescription could be used but it still could induce errors as the garments are not fitted at the right place and time.

Positively, the procurement route allowed 52% of patients to be fitted on the actual day of their appointment and for those patients waiting, the average time was 10 days for ready to wear and 14 days for made to measure garments. Reductions in the time waiting for garments would not only have positive health implications for the patient enabling prompt management of their lymphoedema and possibly improved outcomes and experiences, but it would also indicate a cost-saving due to the avoidance of any health-related consequences due to time lags such as superficial wounds and cellulitis.

However, this evaluation highlighted that even though 2814 patients were fitted on the day a further 2230 could have been fitted if the ready to wear stock had been available. Nevertheless, stock analysis requires dedicated administration staff, which would be required if this service design was accepted as business as usual. The analysis also showed that delays in receiving compression garments longer than 11 days was also identified as ‘admin’ problems. Therefore, a band 3 administrator would support even more efficiencies if this was a permanent service redesign.

Research also suggests that the prescription route for garments is not efficient and has reported numerous risks of waste, harm and variation (Woods, 2018; Board and Anderson, 2018). Although each compression garment does have a unique code for ordering these are not readily available on the GP and CPs systems, thus errors can occur in what was prescribed and what was dispensed. Throughout the procuring process all patients received the correct garment. There is a benefit in being able to try garments on patients and easily alter the size needed based on clinical expertise.

This evaluation is the first to investigate the costs of the prescribed and procured process for compression garments. It was established there is a statistically significant difference in costs when using prescription to procuring. When all costs are considered, there is an individual patient cost saving of £71.10 (SD £40.80) when procuring is compared to prescription. This difference in cost is also seen as statistically significant (P-value <0.001). The differences between the processes indicate the potential for substantial savings to be made if the prescription method was switched to procuring the garments bypassing GPs, clerks and CPs. This would ensure patients are seeing the right people in the right place and not involving superfluous layers in a process and supports value-based healthcare (Gray, 2017). Sustainability of GP and CPs time is vital and the procuring process ensures that they are not being asked to perform tasks with little value.

The prescription process will also minimise patients having to travel unnecessarily for additional fitting appointments. This will help reduce unnecessary spending for patients and limit the reported stress of parking at acute hospital sites. Looking to the environment, there may be capacity to positively influence climate control (use of fossil fuels and emissions). If an average of 10.8 miles per patient was calculated (Iredale et al, 2013), then changing to the procurement process would decrease annual travel (58 000 miles based on 5392 contacts using a prescription based service compared to 5000 miles based on the 461 fitting appointments in this procurement evaluation). This is likely a conservative estimate given that access to garments will likely improve as the procurement initiative embeds.

Although CPs may have developed knowledge in compression for venous ulceration, the number of garments available for lymphoedema is vast; tens of thousands of lines because of an abundance of sizes, manufacturers, designs, colours and fabrics. This lack of clarity in ordering with unknown manufacturers’ causes costly mistakes especially for locally owned pharmacists and not all offer pharmacy discounts. The financial element may not be a burden when the garment costs pounds but when compression can be hundreds it does impact. So much so, that prior to this service evaluation, some CPs were reluctant to dispense prescriptions, causing unnecessary anxiety with patients.

In making this service evaluation a permanent service redesign, a dedicated administration is required. Even when a new band 3 administrator was costed into the analysis, there still remained efficiencies compared to the prescription route. Subsequently, six out of the seven health board services in Wales now have supported the service redesign and compression is procured instead of prescribed. This service evaluation has led to improved patient outcomes, avoided waste, harm and variation.

Conclusion

The analysis has provided a first in-depth examination on the potential health and economic benefits of changing the process of accessing lymphoedema compression garments from prescribing to procuring. The findings suggest substantial differences in costs when comparing prescribing to procuring processes. There is also a substantial time lag in the prescribing process with the adding of healthcare workers with no patient value and is purely based on finance budgets involving primary and secondary care.

The analysis indicates the potential for substantial savings to the NHS (£71.10 per patient), and benefits to patients in terms of timely and quality of care. For the two lymphoedema services alone over one year, the potential cost avoidance would be £38 3371. Further analysis and evaluation is needed, but it seems very likely that using the procurement process would be highly efficient to the NHS. It would also be cost-saving to the patient due to out of pocket expenditure savings incurred by travel between GP practices and CPs. This would also enhance patient care, patient safety and effectively reduce wastage and streamlining this process is in line with delivering value-based healthcare.

Key Points

- Compression garments are vitally important in the management of lymphoedema

- Accessing compression garments via prescriptions can be long-winded and provides little value for patients in superfluous tasks

- Improving the process of procuring instead of prescribing garments may offer many benefits including efficiencies and more effective care.

CPD reflective questions

- Think about the current process for patients to gain compression garments-is it effective? Have you encountered waste or harm?

- Have you experienced difficulties or confusion in obtaining the correct compression garments for patients as there are thousands of different options?

- What education have you received in prescribing compression garments? Is it from independent (non-biased) sources or based on manufacturers guidance?

- Are there other areas that may benefit from direct purchase instead of prescribing? For example stoma products? Incontinence? Nutrition supplements?