Acute sore throat (AST) is a common condition, with 31% of all adults reporting it in 2014; of these, 38% visited a GP for treatment (Kenealy, 2014). The majority of ASTs have an unknown or viral aetiology, with Group A beta-haemolytic Streptococcus (GABHS) identified in only 5–15% of all cases (Cooper et al, 2001). This percentage is lower in children, in whom 1% have GABHS-positive swabs (Hsieh et al, 2011). AST with a viral or bacterial cause is predominantly a self-limiting condition that resolves with simple symptom relief alone (Donowitz, 2021); approximately 40% of cases spontaneously resolve within 3 days of onset.

Historically, untreated GABHS was linked to high rates of acute rheumatic fever (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018). Early and aggressive antibiotic treatment for AST has been found to reduce rates of the disease and has become a key reason for antibiotic prescribing; however, Petersen et al (2007) found that antibiotics were prescribed unnecessarily to 64% of primary care patients whose AST was not found to be caused by GABHS. This raises concerns around prescribing stewardship, the risks associated with inappropriate antimicrobials and the harm that can be caused by unnecessary treatments. A Cochrane review (Spinks et al, 2013) found that antibiotics provided only modest resolution of symptoms, shortening symptom duration by 16 hours compared to symptom relief alone.

Antibiotic stewardship is a key standard in the Royal Pharmaceutical Society guidelines (RPS, 2021) and is backed by numerous governing bodies (Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC), 2019; Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC), 2019; General Medical Council (GMC), 2021), as the indiscriminate prescribing of broad-spectrum antibiotics leads to the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2018).

To address widespread clinical variability in the treatment of AST, Centor et al (1981) developed a scoring system to ascertain which tonsillitis patients were likely to have GABHS infections and, therefore, benefit from antibiotics. In the UK, NICE (2018) recommends two AST clinical scores: Centor and FeverPAIN (Little et al, 2013) (Table 1). This may cause confusion among clinicians as the scoring systems are subtly different, increasing the risk of errors in prescribing practice. Despite this guidance, antibiotic prescribing rates remain high across both adult and paediatric populations (Freer et al, 2017). This raises the question of whether clinical scores are being reviewed and documented in patients’ notes and whether the NICE standard is being adhered to for prescribing antibiotics (NICE, 2018).

Table 1. Centor and FeverPAIN scoring systems

| Centor score | FeverPAIN score | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Absent cough | +1 | Fever in last 24 hours | +1 |

| Exudate on tonsils | +1 | Exudate on tonsils | +1 |

| Lymphadenopathy (swelling of lymph nodes, glands involved in fluid drainage from the lymphatic system) | +1 | Attend within 3 days | +1 |

| Fever | +1 | Severely inflamed tonsils | +1 |

| Absence of cough/coryza | +1 |

For this evaluation, the primary aims were to:

- Review numbers of clinical scores documented in clinical clerking

- Review documentation of symptoms included in clinical scores

- Review the rate of antibiotic prescribing

- Assess appropriateness of prescribing measured against clinical score recommended by NICE NG84 (2018).

Method

Study design

This service evaluation was conducted as a retrospective review of clinical clerking in the emergency department of a large, metropolitan NHS Trust with an urgent and emergent attendance profile of 146 495 between 1 October 2020 and 30 September 2021, including adult and paediatric patients. The department is staffed by doctors and advanced clinical practitioners (ACPs). As a teaching hospital, the department employs doctors at various stages of training, from Foundation Year 1 to consultant, as well as a large number of locums. The ACPs specialise in emergency medicine, either as a sole paediatric specialist or covering adults and paediatrics, and are categorised as trainee or qualified.

The Trust's electronic patient record system was used to access scanned patient data. Emergency department notes were individually reviewed, and the data was entered into a spreadsheet. Patient data was anonymised and each individual given a unique identifier. As this was a retrospective evaluation with no interventions made in patient care during the review, ethical approval was not required.

Data collection

All patients admitted with the presenting complaint of AST or coded as ‘tonsillitis’ between 1 October 2020 and 30 September 2021 were reviewed.

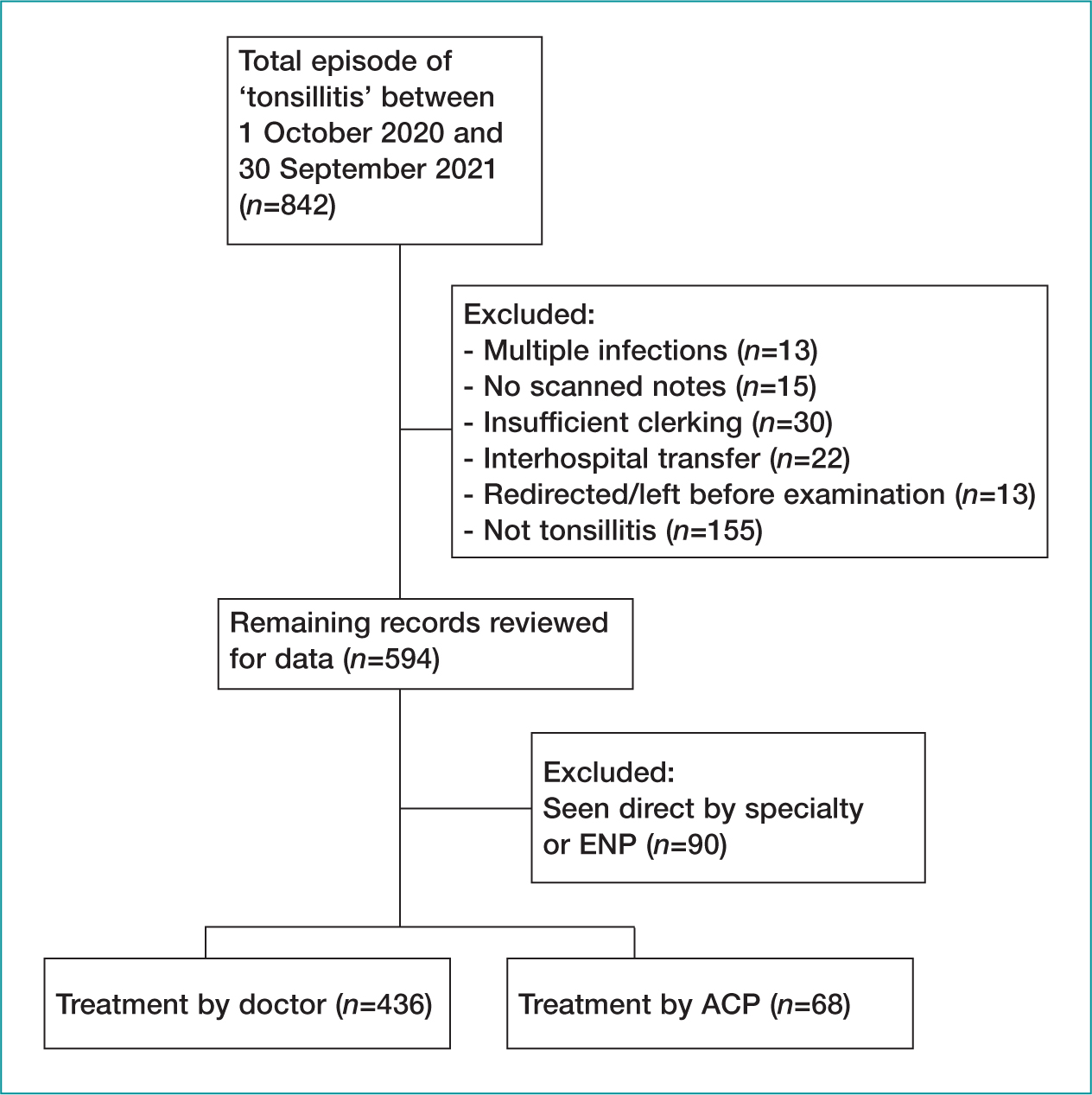

The electronic patient record, including scanned records and discharge letter, was reviewed to establish if the patient was diagnosed with tonsillitis. Patients were excluded if they were diagnosed with multiple infections or were seen directly by a specialty team. Records were also excluded if the scanned records were unavailable or incomplete, the clerking was illegible, or there was insufficient examination documented (Table 2).

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

|

|

Clerking was reviewed to ascertain if a clinical score was documented and what that score was. History and examination were then interrogated to review if all symptoms involved in the score were documented. If these were documented, a score was calculated; if symptoms were missing, this was logged and an estimated score was calculated presuming the symptom was not present. The clerking and discharge letter were reviewed to determine whether a prescription was provided and for which antibiotic.

The accuracy of the prescription was judged against the NICE standard NG84 (2018):

‘Patients with a FeverPAIN score 4 or 5 or a Centor score 3 or 4, consider an immediate antibiotic or back-up antibiotic prescription.’

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe frequency of clinical score documentation, symptom documentation and antibiotic prescription rates. The initial plan to ascertain non-inferiority statistics between clinician groups was unsuitable due to the difference in sample size for each group, which reflects the make-up of the workforce (8% ACPs vs 92% doctors). An attempt to provide matching cohorts to facilitate this was also unsuccessful. Instead, odds ratios (OR) were calculated for four key items: Centor score documented, FeverPAIN score documented, full Centor symptoms, and full FeverPAIN symptoms.

Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using SPSS V.28 (IBM Corp. Released 2021) and GIGAcalculator (Georgiev, 2017). These were assessed for statistical significance (where p<0.05).

During data collection, 146 495 patients who attended the emergency department during the evaluation period were identified for audit. After review (Figure 1), 594 met the inclusion criteria (Table 2). A total of 90 patients were seen directly by specialty teams or ENPs, 155 were incorrectly coded as tonsillitis (e.g. peritonsillar abscess, foreign body, tumour), and 30 had insufficient clerking available for audit.

Baseline sociodemographic characteristics are shown in Table 3. The results show that 52% of patients were male (n=261) and 48% female (n=243); 59% were age 4–64 (n=297), 41% <3 (n=206) and 0.17% >65 years (n=1); and 134 patients had already been seen by another healthcare practitioner before their emergency department attendance.

Table 3. Sociodemographic factors associated with appropriate treatment

| Appropriate treatment n=314 | Inappropriate treatment n=177 | Justified treatment n=13 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Age | ||||||

| <3 | 138 | 43.9 | 61 | 34.5 | 7 | 53.8 |

| 4–64 | 175 | 55.7 | 116 | 65.5 | 6 | 46.2 |

| >65 | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 153 | 48.7 | 97 | 54.8 | 11 | 84.6 |

| Female | 161 | 51.3 | 80 | 45.2 | 2 | 15.4 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| White British | 143 | 45.5 | 60 | 33.9 | 6 | 46.2 |

| White other | 8 | 2.5 | 6 | 3.4 | 0 | 0 |

| White & black Caribbean | 1 | 0.3 | 3 | 1.7 | 0 | 0 |

| White & black African | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| White & Asian | 2 | 0.6 | 3 | 1.7 | 1 | 7.7 |

| Any other mixed | 5 | 1.6 | 3 | 1.7 | 0 | 0 |

| Asian Indian | 4 | 1.3 | 2 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Asian Pakistani | 48 | 15.3 | 39 | 22 | 1 | 7.7 |

| Asian Bangladeshi | 3 | 1 | 5 | 2.8 | 0 | 0 |

| Asian other | 7 | 2.2 | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 |

| Black Caribbean | 4 | 1.3 | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 |

| Black African | 6 | 1.9 | 3 | 1.7 | 0 | 0 |

| Black other | 2 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chinese | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 |

| Any other | 8 | 2.5 | 7 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Not stated | 72 | 23 | 43 | 24.3 | 5 | 38.5 |

| Score documentation | ||||||

| Centor documented | 25 | 8.0 | 1 | 0.6 | 4 | 30.8 |

| FeverPAIN documented | 7 | 2.2 | 1 | 0.6 | 4 | 30.8 |

| First contact health professional | ||||||

| Yes | 223 | 71.0 | 139 | 78.5 | 8 | 61.5 |

| No | 91 | 29.0 | 38 | 21.5 | 5 | 38.5 |

Results

Prescribing

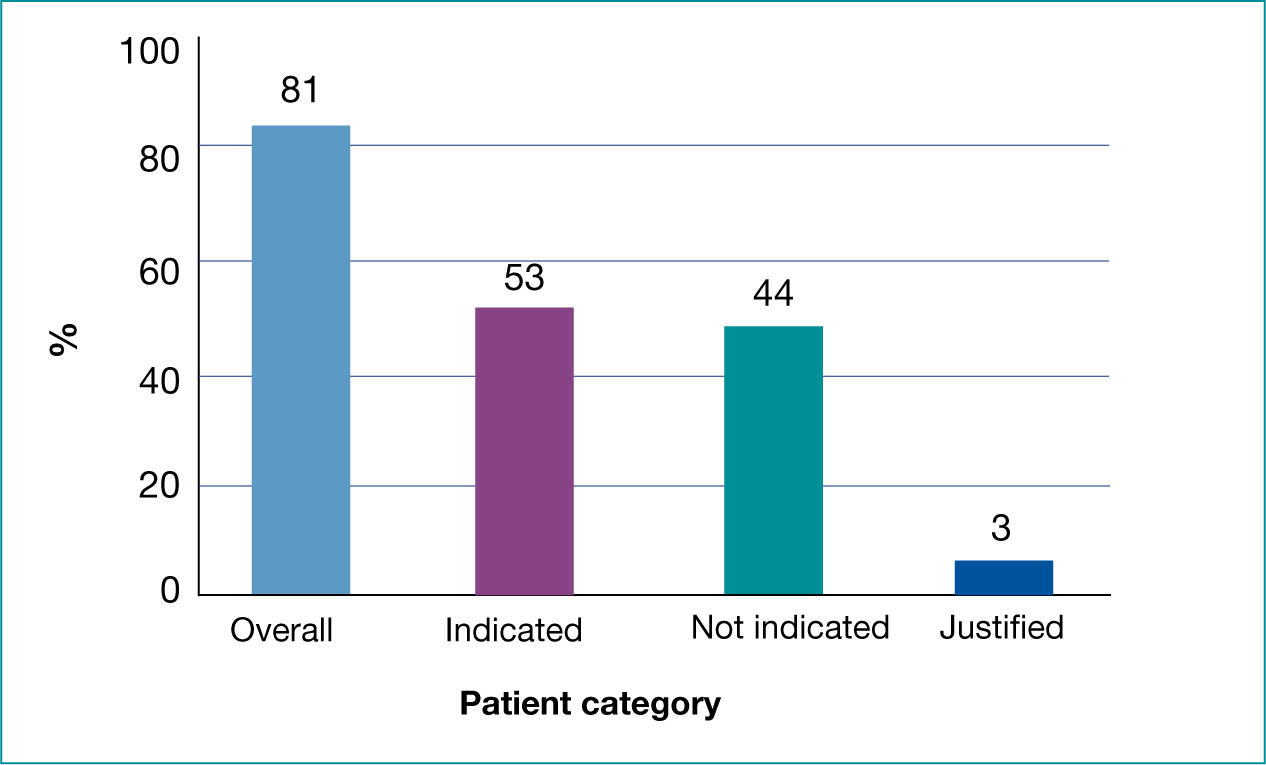

Eighty-one per cent (n=407) of patients received an antibiotic prescription, with 53% (n=216) of these being indicated (Figure 2). Thirteen of 407 patients were clinically septic or immunocompromised and received antibiotics while only totalling a low score and were, therefore, classified as ‘justified’. A further six patients (1%) were indicated to receive antibiotics but did not receive a prescription.

In total, 62% (n=314) received appropriate treatment – either appropriate prescription or appropriate self-care/no prescription. Once the ‘justified’ category was removed, there was a significant difference between groups having a Centor score documented and receiving appropriate treatment compared those with no documented score (OR 15.28, 95% CI 2.05-113.75, p=0.0078). There were no other significant differences between groups when assessing FeverPAIN documentation or full symptom documentation (Table 4).

Table 4. Factors associated with receiving appropriate treatment measured against inappropriate treatment

| Factors associated with receiving appropriate treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Centor Score documented | 15.28 | 2.05 to 113.75 | 0.0078 |

| FeverPAIN documented | 4.02 | 0.491 to 32.993 | 1.94 |

| Full Centor symptoms | 1.18 | 0.776 to 1.8 | 0.436 |

| Full FeverPAIN symptoms | 1.34 | 0.919 to 1.943 | 0.12 |

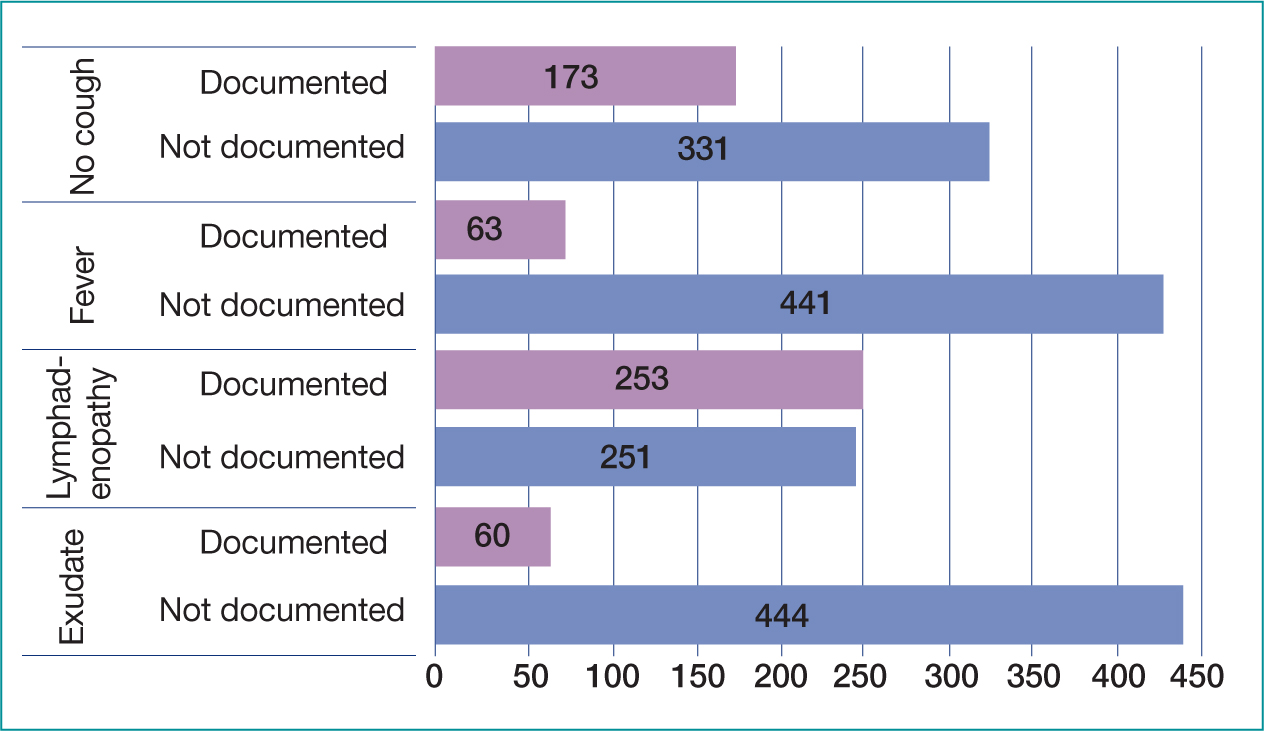

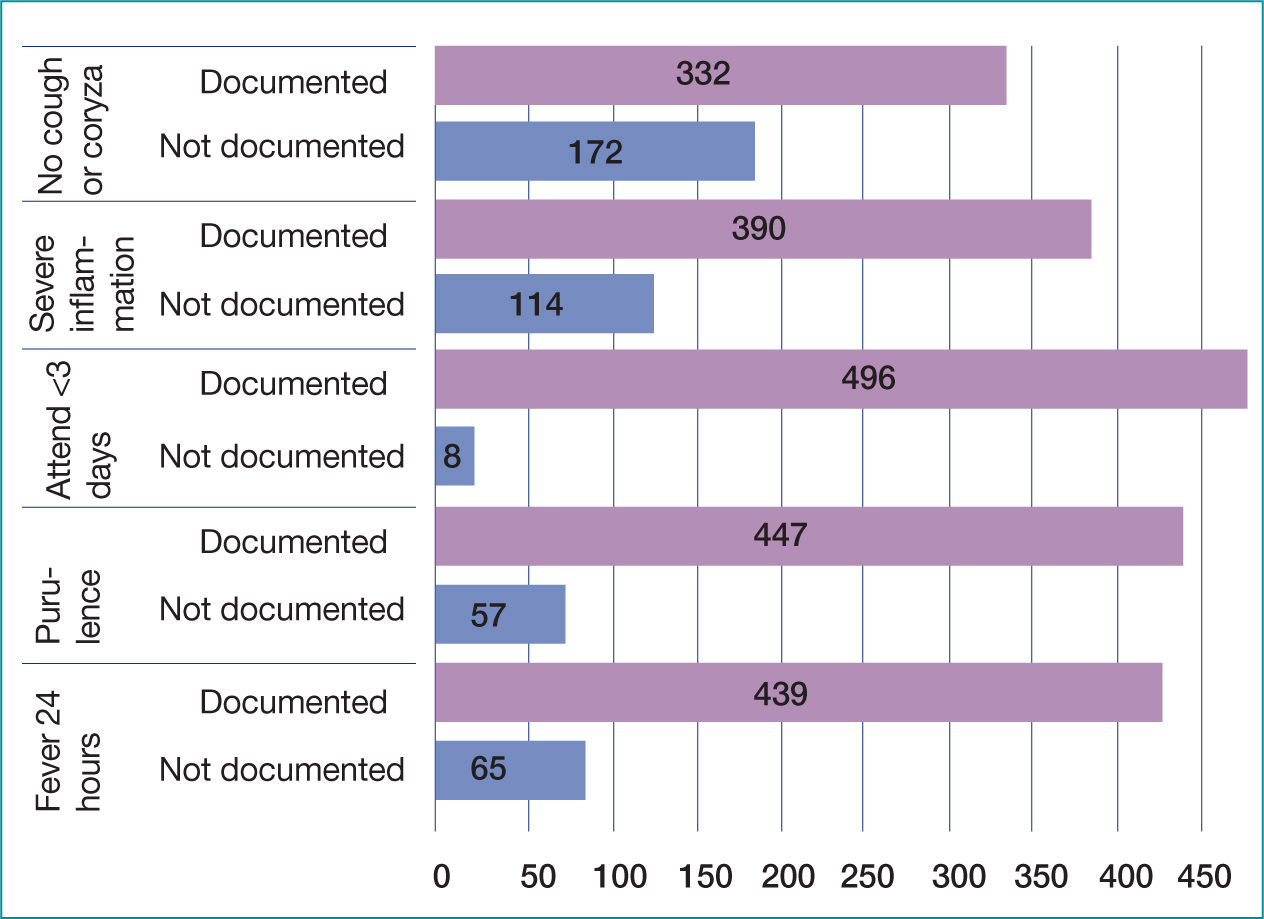

Documentation

A total of 8% (n=39) of cases had scores documented (Table 5), either FeverPAIN or Centor, of which 10 Centor were judged incorrect. Overall, all items of the Centor score were documented in 27% of cases (n=138) and FeverPAIN in 45% of cases (n=225) (Figures 3 and 4). If a symptom was not documented, the score was calculated as that symptom not being present (e.g. no exudate, no cough) using the medical standard of ‘not documented not present’ (Leach, 2015; Mathioudakis et al, 2016). Fever was the most documented symptom; overall, 88% (n=441) of cases had fever or lack of fever recorded, 12% (n=63) making no mention of fever. Lymphadenopathy was the least documented symptom, not documented in 50% (n=253) of cases overall (Figure 3).

Table 5. Symptom documentation

| Overall | ||

|---|---|---|

| % | n | |

| Score documented | ||

| Centor | 6% | 31 |

| FeverPAIN | 2 | 8 |

| Full symptom documentation | ||

| Centor | 27% | 138 |

| FeverPAIN | 45% | 225 |

| Symptom documentation | ||

| Fever | 88% | 441 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 50% | 251 |

| Exudate | 88% | 444 |

| Absence of cough | 66% | 331 |

| Fever in 24 hours | 87% | 439 |

| Duration of symptoms/within 3 days | 98% | 496 |

| Severity of Inflammation | 77% | 390 |

| Absence of cough/coryza | 66% | 332 |

Discussion

The results show that some antimicrobials were prescribed unnecessarily. A total of 407 patients received an antibiotic prescription and only 222 patients had a severe enough score to indicate antibiotics. The evaluation also found that the emergency department had higher rates of antibiotic prescribing for AST than in primary care (76% emergency department vs 60% GP) (Gulliford et al, 2014); but despite this, had a similar proportion of inappropriate prescriptions (44% emergency department vs 47% GP) (Stuart et al, 2020). Other emergency department studies have shown inappropriate rates varying between 63 and 91.7% (Koslover, 2021; Muthanna et al, 2022).

There is anecdotal evidence to suggest patient expectation is a key feature in antibiotic prescribing (Whittaker, 2018). In the high-pressure environment of the emergency department this may be more prevalent and perceived as a quicker option than explaining why antibiotics are not required. Yet Ong et al (2007) found that emergency department patients treated without antibiotics had the same satisfaction rates as those who were. Alarmingly, there is also evidence that by providing antibiotics, the patient is more likely to return for antibiotics with their next AST (Little et al, 1997).

The results also show that documentation of clinical scores was poor (8%), with previous emergency department documentation rates varying from 0–35% (Kanji et al, 2016; Duthie et al, 2020; Dodd and Atkinson, 2021; Koslover and Levene, 2021). Dodd and Atkinson (2021) conducted a similar review of score documentation in order to calculate Centor scores; however, they excluded any patient who did not have the four key symptoms documented, in total excluding 52% of the study population. This grossly limits the sample size in the study and increases the risk of confirmation bias. Clinicians who document the full score or symptoms involved are more likely to be aware of the clinical scoring system and its application (Saengcharoen et al, 2016). This study shows that documentation of a Centor score increases appropriate treatment rates (OR 15.28, 95% CI 2.05 – 113.75, p=0.0039), yet documenting the full symptoms only increased appropriate prescribing rates with Centor symptoms not FeverPAIN. The high rates of poor symptom documentation may explain the extent of over-prescribing of antibiotics. This is clinically relevant as it highlights a potential lack of awareness of the reasoning behind antimicrobial prescribing in AST.

The application of ‘not documented, not present’ can be seen as a limitation to this study. Despite this approach being frequently used in medical litigation, not having full criteria is often used to exclude patients from audit, due to having inadequate information. These cases were included to highlight the link between symptom awareness and appropriate treatment, yet may provide errors in the data, skewing the findings.

The recent introduction of an electronic clerking system in the study emergency department may solve this concern. Enforcing a tick box Centor score when coding patients as tonsillitis; only allowing antibiotic prescription if the score is 3–4, could greatly improve compliance to NICE guidelines and reduce inappropriate prescribing rates.

Although clinical scores have been well researched in terms of their predictive factors for GABHS identification, there is debate regarding the true gold standard. NICE does not currently recommend point-of-care swab testing due to reported poor sensitivity, despite a systematic review finding sensitivity to be consistently 85% and specificity 95% (NICE, 2018; Craig et al, 2020). However, a number of developed countries including the US, Finland and France, now strongly recommend POC testing prior to antimicrobial prescribing (Chiappini et al, 2011).

There is also dispute regarding the specificity of POC swabs, with approximately 20% of positive swabs actually being asymptomatic GABHS carriers (Khan, 2021) not requiring antimicrobials. Further research has combined the differing approaches by using a low clinical score to rule out GABHS, and patients with a high score receiving a POC swab to confirm the presence of GABHS prior to antibiotics; this has been shown to be the most cost-effective method (Giraldez-Garcia et al, 2011). In a small-scale study Llor et al (2010) also found that POC testing improved antibiotic adherence (88.1% vs 76.5%, p<0.01) against clinical scoring alone. There is further debate regarding the use of clinical scoring systems in children under 3 years of age. Neither Centor nor FeverPAIN have been researched in this age group; however, new scoring systems such as McIsaac (McIsaac et al, 2004) include this age group but are not yet recommended by national guidance.

Guidance in the US (Shulman et al, 2012) suggests there is no indication for testing or scoring children <3 years due to GABHS being uncommon with a significantly lower risk of ARF (a working group set up by the Finnish Medical Association's Duodecim, 2020). This is supported by the Committee on Infectious Diseases (2021), which states that children with symptoms suggesting viral infection (e.g. coryza, cough) should neither be tested nor treated as GABHS infection.

The majority of research into AST has been conducted in the primary care setting. The current strain on primary care means the public are now turning to emergency department for minor conditions. The Royal College of Emergency Medicine (RCEM) has little mention of AST treatment in its current curriculum, and no mention of relevant clinical scoring systems (RCEM, 2021), which may explain some of the poor documentation of clinically important symptoms and inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in the emergency department. The over-prescribing of antimicrobials has significant clinical relevance with inappropriate antimicrobials causing increased rates of antibiotic resistance, which is one of the greatest threats to global health (WHO, 2020).

As bacteria become resistant, more expensive and potentially harmful treatments are necessitated, which often require hospital admission and multiple courses of treatment, increasing the burden of previously minor illnesses on the health economy. The development of new antibiotics is slow and complex, and despite these developments none are expected to be effective against the most dangerous antibiotic resistant bacteria (WHO, 2020).

Although there are no reported cases of penicillin-resistant GABHS infections, this review showed that clinicians are using broad spectrum antibiotics such as co-amoxiclav and ceftriaxone for the treatment of uncomplicated AST (n=29/407). This poses significant risk to increasing antibiotic-resistance (Cižman and Plankar Srovin, 2018).

Despite research showing that the majority of all-cause AST is self-limiting, there is still concern regarding non-suppurative sequalae that were previously common but are now rare in the developed world. ARF is an immune-mediated disease that has been linked to GABHS infection (Spinks et al, 2013), although this research was conducted in the 1950s (Denny et al, 1950) when ARF rates were substantially higher (NIHR, 2015). The concerning feature of ARF is the suppurative development of rheumatic heart disease (RHD) causing permanent cardiac damage (Bennett et al, 2022).

In 2015 there were approximately 34 million people living with RHD (Watkins et al, 2017). The American Heart Association (Gerber et al, 2009) quotes this link with ARF as the justification for routine use of antibiotics in AST; yet the numbers needed to treat and prevent one case of ARF in the developed world is reported as 1:10000 (Berkley, 2018). This is likely to present significant risk of harm from drug-related reactions, antibiotic resistance and a significant burden on the health economy. There is also ongoing rhetoric that the link between antibiotic treatment and reduced ARF rates are coincidental, as ARF rates were dropping prior to antibiotic development (Berkley, 2018); and in well controlled communities with high rates of ARF, there was no link found between GABHS or antibiotic treatment (CDC, 1987). This research is grossly out of date, and as rates of ARF and RHD are so low in the developed world (Steer, 2015) the lack of evidence for early treatment of GABHS being effective in reducing the risk of ARF is increasingly being recognised (Ralph et al, 2020).

Limitations

This was a small-scale single-centre retrospective observational review set in a metropolitan emergency department with a highly diverse local community. This means the findings may not be generalisable to other emergency departments or community healthcare practice. The study was also conducted by a single assessor reviewing scanned images of handwritten clerking. This poses a significant risk for error as interrater reliability cannot be calculated. Scanned images may make it difficult to read and points may be missed or misinterpreted.

Another key limitation of this study is the grouping of clinician grades. Foundation year doctors and trainee ACPs were grouped alongside consultants and senior ACPs. The reliance on junior staff, who have not yet undergone specialty training, to see ‘minor illness’ may be disproportionately affecting the findings. There is also no consideration of the background of the large transient workforce such as locum doctors, who have often trained abroad, and who may base their clinical decision making on different disease pathology and prevalence.

Further research

This study highlights the ongoing and clinically inappropriate over-prescribing of antimicrobials for AST and the need for further research. A large-scale, up-to-date randomised controlled trial is required to review effective treatment of AST and the side effects/sequelae of differing treatments both in emergency departments and more broadly in primary care. The use of POC swabs vs scoring system could be incorporated into this with bacterial throat culture being held as the gold standard. This would allow current UK incidence of GABHS infections to be calculated, alongside current rates of GABHS-related ARF.

It may also be beneficial to conduct qualitative research into why clinicians prescribe antimicrobials when they are not indicated to better understand their decision making, what patients expect from attending emergency departments with AST, and how public health education can be improved.

Conclusion

The present study found that clinical scoring is grossly underused in emergency department practice. This coincides with dangerously high rates of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing and potential harm to patients from poor antibiotic stewardship, showing that clinicians are not abiding by the RPS framework, which is the foundation of safe professional practice. These findings support the results presented in wider primary care literature.

The relative low level of score documentation and the ongoing debate regarding accuracy of clinical scoring systems suggests that further research into POC testing is needed and will greatly reduce the antibiotic burden of AST and prevent future antibiotic resistance. Targeted education for clinicians and patients is also needed exploring antibiotics vs self-care treatment alone.

Key Points

- Clinical scoring systems are infrequently used in emergency departments

- Symptoms included in scoring are poorly documented

- Antimicrobials are over-prescribed in acute sore throat in emergency department practice

- This coincides with dangerously high rates of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing and potential harm to patients from poor antibiotic stewardship

CPD reflective questions

- Thinking about the last acute sore throat you treated, did you utilise a validated scoring system to decide on treatment?

- Have you felt pressured to prescribe antibiotics, and how did you react to that?

- If antibiotics were not prescribed, did you explain why to the patient and provide health education?

- If rapid POC testing was available would this change your prescribing practice?