There are several tiers to the English legal system, including criminal law and civil law (Table 1). In criminal law, the police arrest and charge a person for breaking the law. The Crown Prosecution Service brings the case to court, where the person has to be found ‘guilty beyond reasonable doubt’. In civil law, an individual brings an action against another person or organisation. The case is heard in a civil court, and the person may be found guilty on a ‘balance of probability’, rather than absolutely. It is a lesser burden to prove guilt in a civil court.

Table 1. English Legal System

| Criminal law |

|

| Civil law |

|

| Public law |

|

Implications for prescribers

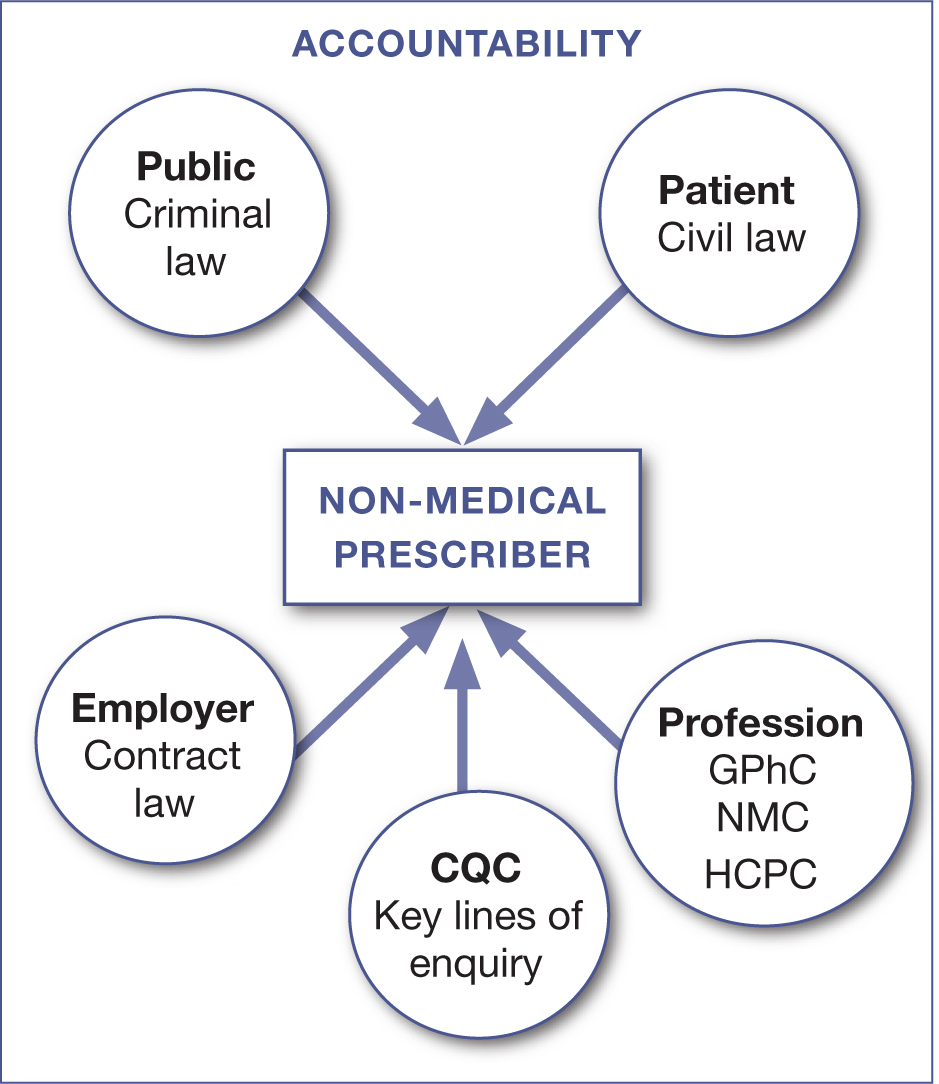

Prescribers can be called to account for their actions by (Figure 1):

- The public, through criminal law

- The patient, through civil law

- Their employer, through their contract of employment

- Their profession, through its code of conduct

- The care quality commission, through key lines of enquiry.

Accountability to the public through criminal law

If a prescriber intended to do harm to their patient and knowingly gave them a drug that would cause harm, the police would investigate and could prosecute for administering a noxious substance to endanger life or inflict grievous bodily harm (GBH).

The Offences Against the Persons Act [1861] contains two offences of wounding or causing GBH, under Sections 18 and 20. Section 18 is the more serious because it carries a maximum sentence of life imprisonment, whereas the maximum sentence under Section 20 is 5 years. The difference is that under Section 18, the prosecution must prove that the defendant intended to cause serious bodily harm, whereas it needs only to show that the defendant acted recklessly under Section 20.

Under both sections, an assault that causes GBH or wounding is defined as: ‘To constitute a wound the whole skin must be broken. It must be more than a scratch, but one drop of blood would be sufficient.’

Both offences under Section 18 and Section 20 are arrestable under Section 24 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act [1984]. They would be tried at Crown Court because either offence carries the potential for a lengthy prison sentence.

The wilful neglect or misconduct can be the result of a positive act or a failure to act. As in the case of R v Dytham (1979), for example, a police officer was held to have been correctly convicted when he made no move to intervene during a disturbance in which a man was kicked to death.

If a prescriber's patient died, the prescriber could be charged with manslaughter if they were found to have caused their death by negligence. Criminal charges are rare, but can attract considerable publicity (Box 1).

Box 1.Case studyThree health professional were called to account for their actions in a criminal court when a 6-year-old boy died in their care. The doctor, the nurse and the ward sister were prosecuted for gross negligence and manslaughter.Jack Adcock, who had Down's syndrome and a known heart condition, had been suffering from diarrhoea, vomiting and had difficulty breathing. Dr Hadiza Bawa-Garba was a specialist register on duty and saw Jack about 10:30am. Jack was receiving supplementary oxygen and Dr Bawa-Garba prescribed a fluid bolus and arranged for blood tests and a chest x-ray. At 10.44am the first blood test was available and showed a very high lactate reading. The x-ray became available from around 12.30pm and showed evidence of a chest infection.Dr Bawa-Garba viewed the x-ray and 3pm and prescribed a dose of antibiotics immediately, which Jack received an hour later from the nurses. A failure in the hospital's electronic computer system that day meant she did not receive the blood results at 4.15pm. She had a handover meeting with a consultant at 4.30pm, and Dr Bawa-Garba noted the high CRP level and recorded a diagnosis of pneumonia. However, he was not reviewed by a consultant as it was felt he was improving. When she wrote up the initial notes, she did not specify that Jack's enalapril (for his heart condition) should be discontinued. Jack was subsequence given his evening dose of enalapril by his mother after he was transferred to the ward around 7pm. At 8pm a ‘crash call’ went out and Dr Bawa-Garba was one of the doctors who responded to it. On entering the room she mistakenly confused Jack with another patient and called off the resuscitation. Her mistake was identified within 30 seconds–2 minutes and resuscitation continued. The courts decided that this hiatus did not contribute to Jack's death, as his condition was already too far advanced. At 9.20pm, Jack died.On 2 November 2015 the agency nurse, 47-year-old Isabel Amaro, of Manchester was given a 2-year suspended jail sentence for manslaughter on the ground of gross manslaughter and later removed from the register by the NMC for failing to do observations of the child, poor record keeping and failing to escalate his deteriorating condition.On 4 November 2015 Dr Bawa-Garba was convicted of manslaughter on the grounds of gross manslaughter at Nottingham Crown court and was given a 24-month suspended sentence was struck off the medical register.On 19 March 2018 the University Hospital of Leicester NHS Trust released a serious incident report into the death of Jack Adcock, which was completed 6 months after his death. The report says that there was no ‘single root cause’ behind the 6-year-old's death.On 13 August 2018, the court of appeal Judge ruled in favour of Dr Bawa-Garbo and felt that she should be suspended rather than erased.On 9 April 2019 Dr Bawa-Garbo was able to return to practice. The ward sister was found not-guilty and staff nurse Isabel Amaro remains struck off.

Two new laws have been brought in to protect vulnerable patients following inquiries into poor care and avoidable deaths of patients in Mid Staffordshire and South Wales where concerns were raised at how patients with dementia were being care for at two hospitals and an independent review was commissioned (House of Commons, 2013; Andrews and Butler, 2014). The government has sought to restore public confidence in their supervision and management of the NHS by making it a criminal offence to ill-treat or wilfully neglect a patient in your care (Criminal Justice and Courts Act [2015], section 20).

Accountability to the patient through civil law

If a patient has suffered harm or loss due to a prescriber's actions they could bring a civil action to be compensated, particularly if they became too unwell to work. The plaintiff (patient) would only have to prove on a ‘balance of probability’ that the prescriber were to blame. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society (2016) introduced A Competency Framework for all Prescribers, which governs all prescribers including medical and non-medical prescribers and are the standards that all prescribers are judge against in civil law. If it could be proved that a prescriber fell below the expected standard, such as failing to find out if a patient was allergic to penicillin or prescribing a drug that interacts with their existing medication, the prescriber would be liable.

Accountability to the employer through their contract of employment

A non-medical prescriber is accountable to their employer through the contract of employment. The contract set out the terms and conditions of employment and the standard of work expected of the employee (Rideout, 1983). An employer is vicariously liable for the actions of its employees, and would have to pay any compensation. Employers minimise the likelihood of liability arising by holding their employees to account through reasonable disciplinary procedures under contract law. Employment law allows a lower burden of proof when deciding whether an employee is guilty of misconduct. Employment law only requires that an employer holds an honest and genuine belief that the employee is guilty of misconduct based on the outcome of a reasonable investigation (British Homes Stores Ltd v Burchell [1980]).

If a prescriber's poor actions were related to their job, their employer could take disciplinary action against them, particularly if the prescriber failed to follow correct procedures and policies and thereby breached their contract of employment. A prescriber must ensure that their prescribing is in line with any policies and procedures and their prescribing practice is in their job description. The employer has full indemnity for their employee's actions as a prescriber and if there are limitations or restrictions in place such as seeing particular patient groups (ie children) or restrictions on particular classes of drugs, the prescriber must be aware.

As well as being accountable to their employer through reasonable disciplinary procedures, a prescriber also owes a contractual duty of care to their employer. A breach for that duty allows an action for damages for breach of contract (Lister v Romford ice and Cold storage Co ltd [1957]). Therefore if an employing Trust or GP surgery pays compensation for negligence of one of their employees, they may seek to reclaim that compensation by suing the employee for a breach of their contractual duty of care.

Professional indemnity insurance

Most professional organisations insist that practitioners have their own professional indemnity insurance. The Nursing and Midwifery Council's (NMC) Code (2018) states (Box 2):

‘Have in place an indemnity arrangement which provides appropriate cover for any practice you take on as a nurse … to achieve this you must: 12.1 make sure that you have an appropriate indemnity arrangement in place relevant to your scope or practice.’

Box 2.NMC (2018) The code of conduct Section 1818 Advise on, prescribe, supply, dispense or administer medicines within the limits of your training and competence, the law, our guidance and other relevant policies, guidance and regulationsTo achieve this, you must:18.1 Prescribe, advise on, or provide medicines or treatment, including repeat prescriptions (only if you are suitably qualified) if you have enough knowledge of that person's health and are satisfied that the medicines or treatment serve that person's health needs18.2 Keep to appropriate guidelines when giving advice on using controlled drugs and recording the prescribing, supply, dispensing or administration of controlled drugs18.3 Make sure that the care or treatment you advise on, prescribe, supply, dispense or administer for each person is compatible with any other care or treatment they are receiving, including (where possible) over-the-counter medicines18.4 Take all steps to keep medicines stored securely18.5 Wherever possible, avoid prescribing for yourself or for anyone with whom you have a close personal relationship

The UK Government has introduced legislation that requires Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) registrants to have a professional indemnity arrangement in place as a condition of their registration with HCPC. Prescribers must also be aware of the level of indemnity to determine whether it is appropriate cover for practising as such.

In situations where an employer does not have vicarious liability, the NMC recommends that registrants obtain adequate professional indemnity insurance. If they are unable to secure professional indemnity insurance, a registrant will need to demonstrate that all their clients and patients are fully informed and the implications this might have in the event of a claim for professional negligence.

Accountability to the profession through the professional governing body

A professional body can remove a registrant's name from their register to stop them practising as a professional if that person does not follow their code of conduct. A registrant must ensure that they apply by their professional body's instructions (eg the NMC (2018) has a section on prescribing practice) on prescribing or they may be removed from the register. Each registrant needs to be aware of any restrictions to their prescribing practice. For example, a paramedic cannot prescribe controlled drugs, and the law under the Maternity Act [1961] states that only doctors and midwives can prescribe pregnancy-related items to pregnant woman.

The police will often inform professional governing bodies of criminal activities, regardless of whether they directly relate to the person's work (eg if they were found guilty of driving under the influence of alcohol, or for theft or fraud).

The Professional Standards Authority for Health and Social Care (PSA) previously known as The Council for Healthcare Regulatory Excellence (CHRE) is an independent, non-departmental public body funded by the Department of Health and answerable to Parliament. It scrutinises and oversees the work of nine regulatory bodies, including the NMC, the General Medical Council (GMC), and the Health Professional Council. If the PSA considers that the decision by a regulatory body has been unduly lenient, it could refer the case to the High Court for a decision.

Prescribing is not within the scope of practice of everyone on the NMC and HCPC's register. Nursing associates cannot prescribe, but they may supply, dispense and administer medicines. Nurses and midwives who have successfully completed a further qualification in prescribing and recorded it on the register are the only people on that register who can prescribe. As a non-medical prescriber it is important to be aware of the various statutory framework that impacts on prescribing (Table 2).

Table 2. Statutory Framework

| Primary Legislation | European Community Law | Secondary Legislation |

|---|---|---|

|

Criteria for determining products which should be available on prescription only – Directive 92/26/EEC |

|

Accountability to the care quality commission, through key lines of enquiry

A fifth sphere of accountability that sits between the employer and profession is the care quality commission (CQC). These CQCs were set up in response to concerns over the safety and quality of health services. All providers of health services, including NHS Trusts, GP surgeries and nursing homes must be registered with the CQC. These places can then be inspected to ensure that they meet with the standard expected (Health and Social Care Act [2008] (Regulated Activities) Regulations 2014) and the CQC can raise individual concerns regards professional to their professional body to take action.

Duty of candour

Openness and honesty begins before care and treatment. The professional duty of candour is not intended for circumstances where a patient's condition gets worse due to the natural progression of their illness. When a prescriber realises that something has gone wrong – this might be due to they have incorrect prescribing – they must speak to the patient. There is no need to wait until the outcome of an investigation to speak to the patient, but you should be clear about what has and has not yet been established. The prescriber must apologise to the patient and explain what has happened and what will be done to prevent this from happening again.

Conclusion

There are five areas of accountability that can affect the prescriber, and the prescriber needs to aware of their actions and omissions and ensure if any harm results that they owe a duty of candour to their patient. Is important that the prescriber is aware of all their responsibilities as well as their accountabilities. They must be up-to date in clinical practice and only operate within their scope of practice.

Key Points

- Prescribers can be called to account for their actions by: the public, through criminal law; the patient, through civil law; their employer, through their contract of employment; their profession, through its code of conduct; and the care quality commission, through key lines of enquiry

- Prescribers have a duty of candour to their patients and must be open and honest

- A prescriber needs to keep their knowledge and skill up-to-date and work within their competencies