Before we go any further, this is not about smoking, drinking, sleep hygiene, diet and exercise. I am assuming you know all this and that you don't want to be hectored into abandoning the glass of wine after work. I am hoping that your curiosity might take you further. The tips that I suggest are evidence based and tested in my clinical practice and in my own life as a nurse, keeping afloat a small community organisation with 20 volunteers.

What is self-care?

According to the National Institute for Mental Health (2024), self-care means ‘taking the time to do things that help you live well and improve both your physical health and mental health’. Self-care, even in small doses, can help you to stay well, lower stress and boost energy. So this means consciously thinking about small changes that you might make to your daily routine to improve your wellbeing.

Take a wellbeing inventory

The UK government established and supported a national organisation called the What Works Centre for Wellbeing between 2014 and 2024. Over those 10 years it has created a vast repository of evidence for what improves our wellbeing. The Centre defines wellbeing at an individual level as whether we are ‘feeling good and functioning well’.

Over 5 months, between 2010 and 2011, the UK Office for National Statistics (ONS) ran the Measuring National Wellbeing Programme. This involved a national debate to determine what makes us well (Oman, 2016). It concluded that wellbeing has 10 broad dimensions (ONS, 2024):

These dimensions of wellbeing are reflected in the ‘what matters to me’ conversations, which are at the heart of social prescribing. So why not make your own ‘prescription’ by using these 10 dimensions as an inventory to track the issues that affect your own wellbeing? The next step (Day 1) is to use the results to understand what you can control. So, for example, if inflation is affecting a tight family budget (items 7 and 8 above) this is going to worry you.

Day 1. Know what you can control

When you aren't in control you become stressed and your cortisol levels rise, affecting your cardiovascular health and more. In a groundbreaking experiment called the Whitehall Studies, which lasted 20 years across two cohorts of British civil servants of different grades, Marmot and colleagues discovered that there was a clear social gradient in the prevalence of disease. (Marmot, 1991). Essentially, the lower down the pecking order you are at work, the less control you have and the more stressed you are.

Of course, you can't control everything in life, so you judge what you can control, maybe by budgeting or getting help with a credit card bill. Instead, you might want to try this exercise shown in Figure 1 (Covey, 1989):

Focusing in this way will help you to become more realistic about what you can do something about and accept things beyond your control.

Day 2. Stay connected

Remember the feeling of being separated from loved ones during the coronavirus pandemic? Findings from the longest ever longitudinal study into the wellbeing of sophomore students, which has lasted over 80 years, confirm that is it the warmth and quality of long-term relationships that is the most important influence on longevity and life satisfaction (Vaillant, 2012). So, if like I did when I was a director in the NHS, you ring your closest friend and say, ‘I just can't make it tonight, I've had a heck of a day’, remember that you are turning down an opportunity to enhance your wellbeing.

The most important connection, however, is with yourself. Kristen Neff is an expert on self-compassion (https://self-compassion.org). She describes how cruelly we often talk to ourselves when we make mistakes. Here's a tip – why not monitor how much you judge and criticise yourself today? Replace the negative self-talk with kindness and understanding, in the way that your best friend might.

Day 3. Do something for others

A friend of mine, a photographer, went to his GP about his low mood. Rather than pills or therapy, his doctor surprised him by giving him three pieces of advice:

It's official: doing good does you good. It can promote physiological changes in the brain, known as the ‘helper's high’ (Luks, 1991) and has positive impacts on happiness, mood, self-esteem and mental health (Post, 2014).

As part of my community development work, I sometimes ask the most in need for help (‘Can you make the tea for me at this event?’) and watch them grow. The effect is not linear (Post, 2014), and those of us in the caring professions need to limit the helping so that it doesn't tip over into burden. We set in place professional boundaries, so this altruistic practice should focus on your personal life.

Day 4. Find meaning and purpose

I have been quite open in the past in saying that I climbed the career ladder into misery. I did what was expected of me, rather than what brought me joy, or meaning to my life; so I changed to do what I love. As the saying goes, I have never worked a day since. If, like me, you find yourself stuck, then apply the same question to yourself today as you ask your patients – what matters to me?

Day 5. Be creative

‘The mind is the gateway through which the social determinants impact upon health, and this report is about the life of the mind. It provides a substantial body of evidence showing how the arts, enriching the mind through creative and cultural activity, can mitigate the negative effects of social disadvantage.’

[Sir Michael Marmot prefacing the All Party Parliamentary report on arts, health and wellbeing, 2017]

Whether you enjoy music, painting or singing, everyone from the World Health Organization (Fancourt and Finn, 2019) to an all-party political committee (see quote above) would exhort you to do something creative. On my most anxious days, I break out the watercolours. My photographer friend surprised the heck out of me at our local camera club, full of reticent 60-something men, by telling everyone how photography helps his mental health and inviting anyone who felt the same to speak to him. Today is the day to try out a creative hobby and try to make it a challenge (see the next day).

Day 6. Get into flow

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi was a world-renowned psychologist whose work focused on what makes you happy. He explained that expensive houses and bigger salaries don't help. In fact, beyond sufficient money to live on, more money doesn't improve happiness (What Works Wellbeing, 2024), although social comparisons drive us to believe that it will (Layard, 2011). What helps is to alter our state of consciousness and, in Csikszentmihalyi's case (2002), this is by entering a state of flow.

We have all been in flow – when we are undertaking an activity that requires absolute concentration. It's so absorbing that nothing else seems to matter and time flies by. Maybe you've been rock climbing or completing a piece of research about your favourite subject. You're so immersed in what you enjoy that you aren't worrying about or regretting anything.

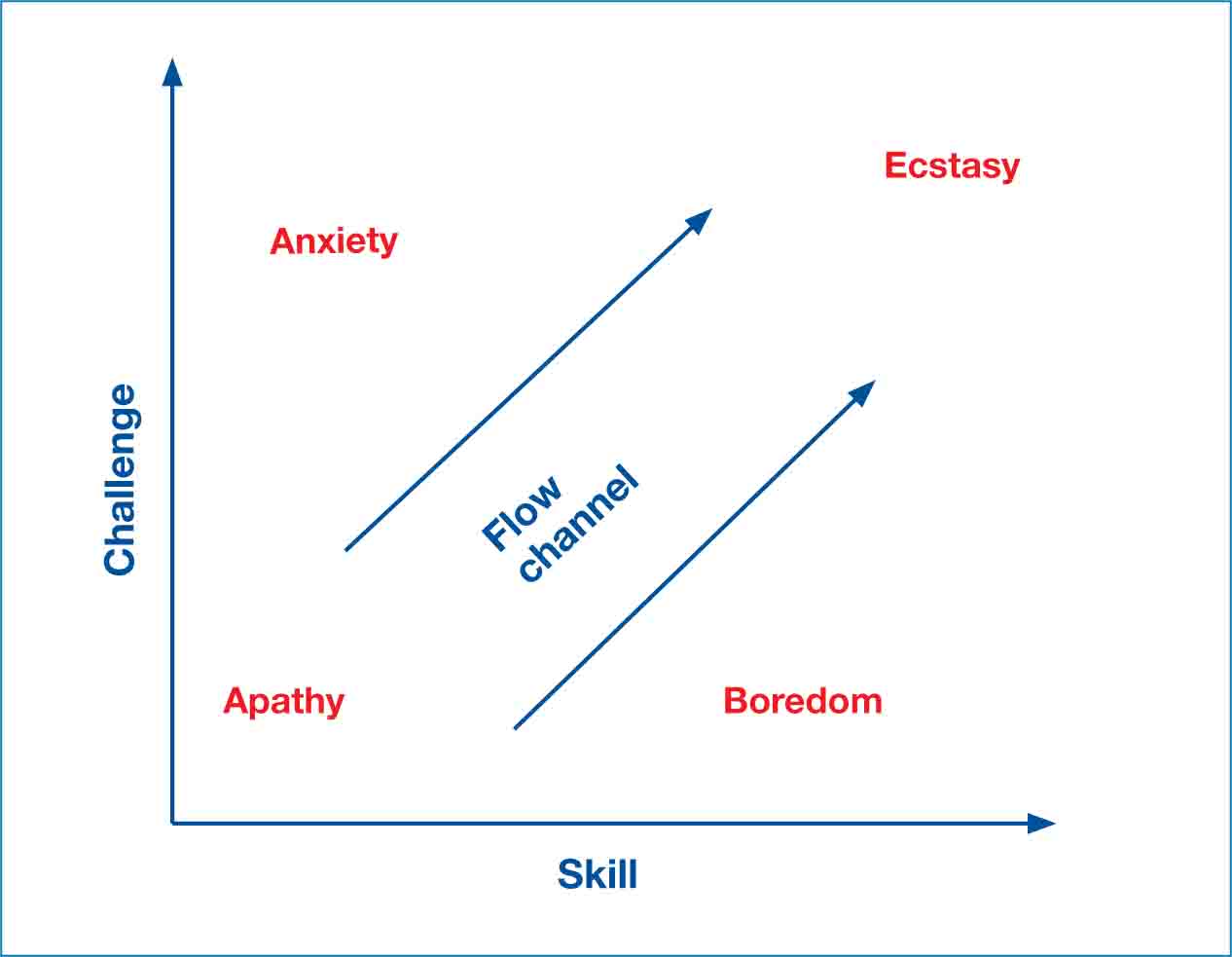

Putting yourself into flow requires the right level of challenge and skill so that you are neither anxious nor bored (Figure 2). By balancing these two you enter the ‘flow channel’. As you increase your challenge you get better, and the more intense the state of flow becomes.

Self-care can be about massage and manicures, lying in the bath or lighting candles. But without challenging ourselves we may still feel our woes. Flow will help us, if we find something that we love to do and keep getting better at it.

Day 7. Get into nature

On your final day of your self-care challenge, it's all about going green. Of course, we might recommend a form of eco – or green – therapy for our patients, such as gardening or forest bathing, but what about ourselves?

We might start the day with ‘sunlight before screen light’ to improve our circadian rhythms. I start the day by inspecting the plants in my garden, with a bowl of cereal in hand.

There is much to learn about why and how nature can make us well. For example, if we take notice of the veins on a leaf or how the petals on a flower occur in patterns, called fractals, this can reduce levels of stress (Taylor, 2016). Trees give us not only oxygen but also chemicals called phytoncides, which increase the levels of natural killer cells in our bodies, improving immunity and resistance to tumour formation (Li, 2009).

Self-care may mean something as simple as looking out of the window at the birds building a nest between patient consultations, a walk in the park at lunchtime or at weekends, or caring for houseplants, a window-box or a back garden.

Summary

Effective self-care requires evidence-based actions to improve wellbeing. To be well, we need to feel in control, have people who care about us and whom we help in return. We need purposeful, meaningful, creative and challenging things to do. And just a touch of nature.