Nutritional Borderline Substances (NBS) are products that have been approved by the Advisory Committee on Borderline Substances (ACBS). These are included in the British National Formulary and can be supplied at NHS expense on a FP10 prescription. They include a full spectrum of products of varying complexity, are used in many diseases, and range from basic oral nutrition supplement products (ONS) to highly specialist metabolic products for treatment of Inherited Metabolic Disorders (IMD) such as phenylketonuria. This review defines appropriate prescribing and examines the data to determine if NBS are being safely and sustainably prescribed, and considers innovation and best practice in this field. Nutritional items categorised as prescription only medicines (POM) are beyond the scope of this review, despite there being issues in common between the two categories. The rationale for why some nutritional products are POM and others are NBS is not discussed. Condition-specific use of NBS and hospital usage are also out of scope.

Defining appropriate prescribing

Tully and Cantrill (2005) describe appropriate prescribing as ‘indicated, necessary, evidence-based (using a broad meaning of ‘evidence’) and of acceptable cost and risk-benefit ratio’. Buetow et al (1997) provide a broader definition; ‘the outcome of the process of decision-making that maximises net individual health gains within the society's available resources’. Both highlight that though there may be a clinical need, prescribing cannot be considered appropriate in the absence of other relevant, objective information, and both specify that affordability must be considered. Grant et al (2013) analyse the variation in prescribing practice and define macro prescribing decisions as those that ‘were collective, policy decisions made considering research evidence in light of the average patient, one disease, condition, or drug’. They describe micro prescribing decisions as those that ‘were made in consultation with the patient considering their views, preferences, circumstances and other conditions (if necessary)’. In nutritional prescribing, decisions are arguably at the micro level, as malnutrition (or support to actively manage nutritional status in disease) is an outcome in various disease states, and, in best practice, the views of the patient on the palatability are prioritised to promote adherence.

Regardless of how appropriateness is defined or the variations in practice are understood, this is in contrast to how we train our workforce to manage prescribing of nutrition:

- Medical curricula vary significantly in how nutrition is taught, with as little as 8 hours teaching on nutrition in total. There is a need to develop teaching and competencies (NHS Long term plan, 2019; Crowley et al 2019)

- Dietetic curricula traditionally focus solely on clinical nutrition and individualised nutritional care planning but usually have not included prescribing processes or management

- Nursing curricula teach identification and management of malnourished patients

- Independent prescribers study physical assessment but combining product choice with ongoing management of NBS is not specifically taught

- Pharmacist curricula also vary widely although nutrition is on the General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC) indicative syllabus (GPhC, 2011).

The lack of shared competencies on this area pre-registration is also widely reflected at postgraduate level, except for specific job roles. This lack of consistent and comprehensive workforce training is complicated further by the issue of prescribing rights. Doctors and other independent prescribers are trained in prescribing, but there is a lack of in depth knowledge of nutrition care planning. Dietitians cannot prescribe independently, but in 2016 gained supplementary prescribing rights. The model of one profession with specialist knowledge requesting prescriptions from nonspecialist prescribers is challenging, as there is a disconnect between the nutrition care process and prescribing. An audit found that 30% of prescriptions were inappropriate for the patient's nutritional needs (Robinson, 2018). Further study is required, but NBS are at risk of a lack of supervision and appropriate use reviews, errors, such as ‘Look Alike, Sound Alike’ (LASA) errors, and insidious harm, such as an incorrect product being prescribed for long durations.

This disconnect between training and prescribing rights is exacerbated by workforce challenges. GPs face significant pressures (Baird et al, 2016) and many state that they do not have the capacity or expertise to prescribe nutrition appropriately (NHS Long term plan, 2019; Crowley et al, 2019). However, dietitians are typically employed by providers and work in a range of specialisms other than primary care. Commissioning of community dietetic support is highly variable and many patients are unable to access basic dietetic care. Whilst it is possible to define appropriate prescribing and extend this to clinical nutrition, it is not possible to identify who is currently responsible.

Analysis of nutrition prescribing data

The Prescription Cost Analysis 2018 (NHS Digital, 2018) shows that the Net Ingredient Costs (NIC) for enteral nutrition, food for special diets, and colecalciferol have risen by 54%, 139%, and 144% respectively in the last decade (2008-2018). Table 1 shows the position of these broad categories compared with specific medicines, and the costs to the NHS.

Table 1. Top 20 drugs by net ingredient cost (NIC)

| Position last year | BNF chemical name | NIC(£) 2018 | NIC(£) 2017 | NIC(£) 2008 | Cost change (£) 2017-2018 (%) | Cost change (£) 2008-2018 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Enteral Nutrition | 264 031 701 | 258 274 198 | 171 268 044 | 5 757 503 (2.2%) | 92 763 657 (54%) |

| 4 | Beclometasone Dipropionate | 237 957 660 | 208 763 160 | 108 146 890 | 29 194 499 (14%) | 129 810 770 (120%) |

| 9 | Apixaban | 223 354 977 | 150 397 309 | - | 72 957 668 (48.5%) | - |

| 1 | Fluticasone Propionate (Inh) | 215 094 504 | 271 942 747 | 351 102 321 | -56 848 242 (-20.9%) | 223 354 977 (-39%) |

| 7 | Rivaroxaban | 194 482 896 | 161 307 500 | 1733 | 33 175 396 (20.6%) | 194 481 164 (11 225 464%) |

| 6 | Glucose blood testing reagents | 169 605 465 | 175 727 365 | 137 127 002 | -6 121 901 (-3.5%) | 32 478 463 (24%) |

| 5 | Budesonide | 144 240 393 | 182 447 367 | 129 705 884 | -38 206 975 (-20.0%) | 16 534 509 (11%) |

| 8 | Titropium | 138 054 901 | 160 505 549 | 98 795 947 | -22 450 648 (-14%) | 39 258 955 (40%) |

| 10 | Other food for special diet preps | 103 265 578 | 104 880 477 | 43 121 194 | -1 614 899 (-1.5%) | 60 144 383 (139%) |

| 12 | Sitagliptin | 92 381 523 | 92 976 422 | 2 937 200 | -594 899 (-0.6%) | 88 444 323 (2246%) |

| 11 | Colecalciferol | 92 099 465 | 94 266 022 | 37 791 4366 | -2 166 558 (-2.3%) | 54 308 098 (144%) |

| 13 | Metfformin Hydrochloride | 91 784 506 | 90 825 310 | 40 497 902 | 959 196 (1.1%) | 51 296 60 (127%) |

| 20 | Influenza | 91 607 127 | 72 679 535 | 59 768 259 | 18 927 592 (26%) | 31 808 868 (53%) |

| 17 | Insulin Aspart | 83 298 592 | 80 042 803 | 57 378 276 | 3 255 789 (4.1%) | 25 920 316 (45%) |

| 16 | Mesakazube (systemic) | 81 786 498 | 80 833 013 | 51 634 507 | 953 485 (1.2%) | 30 151 991 (58%) |

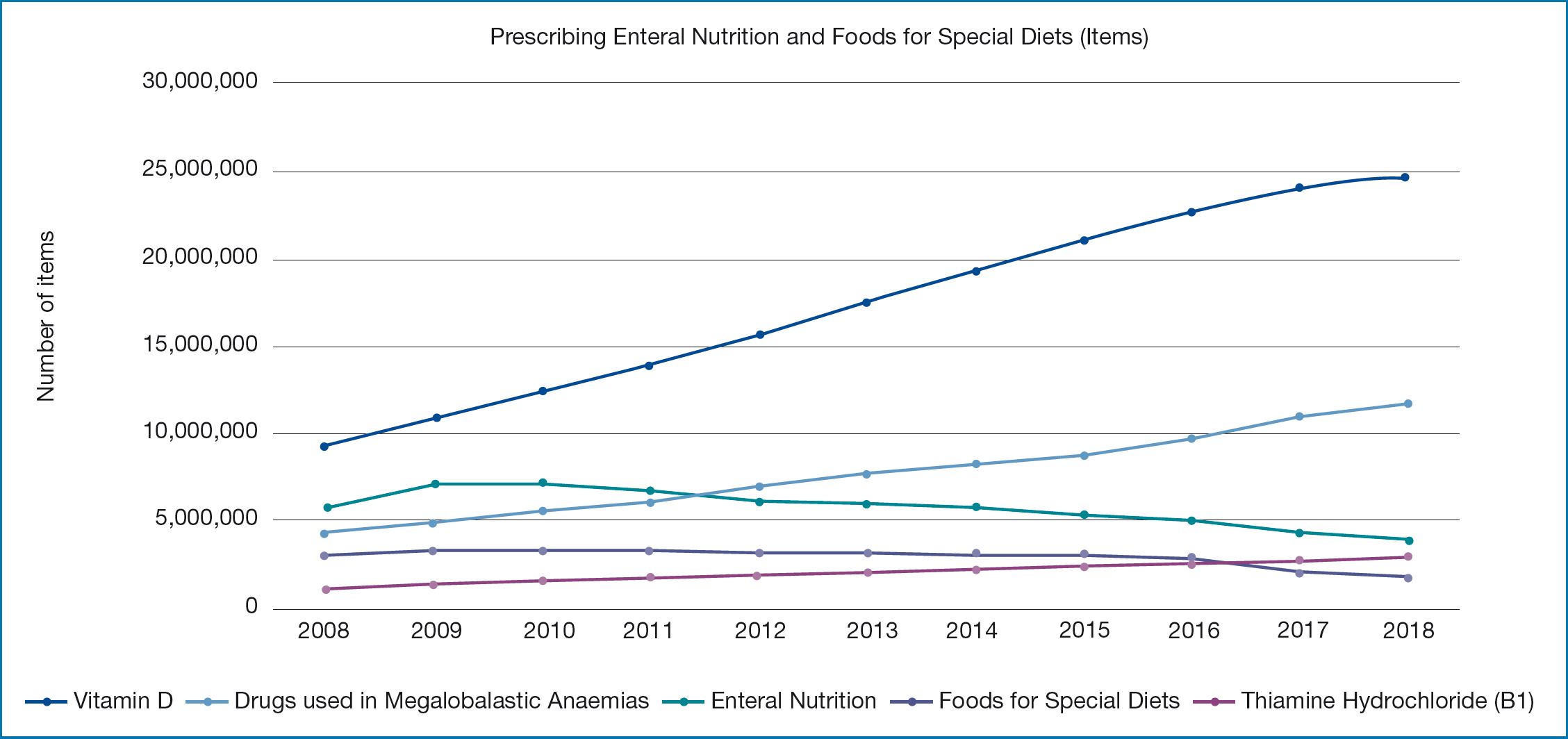

However, the trend in the number of items prescribed presents an even more interesting picture, with slight decreases in the number of items being prescribed for enteral nutrition and foods for special diets, and a significant increase for vitamin D (Figure 1).

The decrease in the number of items prescribed for enteral nutrition and food for special diets is surprising given that the demand is from an ageing population. The decrease in the number of items prescribed for enteral nutrition and food for special diets is surprising given that the demand is from paediatrics, many conditions are lifelong and there is an ageing population (Page et al, 2019). This is in contrast to other nutritional categories such as vitamin D, where the number of items prescribed is increasing. This is likely to reflect the work of GPs, Medicine Optimisation teams, and changes in policy, such as the reduction in gluten-free prescribing (NHS England, 2018).

The increased cost raises the question of value for money and price redistribution across different subcategories of nutritional products. The nutrition supply market is controlled by a few companies and is described as discrete and specialist, with three suppliers competing for provider and home tube feeding contracts (Commercial Medicines Unit, 2017). The market in ONS has significantly more competitors, and this is reflected in the prices of products. Promoting clinically- and cost-effective prescribing of ONS and infant feeds is part of the Medicines Value Programme (NHS England, 2019b), and a common strategy used by Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) to manage rising costs. Changing of prescriptions and the challenging of prescription requests is a relatively new practice. Differences in product choice are frequently the result of a difference between traditionally acute led procurement and budgets, an issue that theoretically may be resolved by Integrated Care Organisations and joint formularies. However, it is worth noting that whilst competition in specific product categories may reduce prices, it is more challenging to address the rising costs of essential tube feeds and specialist products such as low patient numbers and a relative lack of competition in product manufacturers.

Regional analysis of prescribing trends across Integrated Care Systems (ICS), CCGs or even General Practice (GP) footprints, reveal there is little consistency between areas. Whilst some variation according to demographics is to be expected, the level of variation and associated costs are unwarranted. A detailed understanding of the variation is complicated by the number of confounding factors including nutrition supply contract, and varying approaches to commissioning of community dietetic services, public health and medicines optimisation. A voluntary audit of prescribing of NBS upon discharge from hospitals was undertaken and published (Fisher, 2018). This revealed highly variable rates of dietetic-led prescribing (Table 2). There are a number of points which, although regional in scope, are the result of the only audit of this area and the themes are likely to be national. The assumption that all patients prescribed an ONS (or specialist infant formula) at discharge have been assessed by a dietitian cannot be made. Adequacy of screening and referral to dietetics was not in scope. Hospital A is in the highest quartile for dietetic staffing, whilst hospital B is in the lowest quartile (as reported by the head of service using Model Hospital data). Hospital B also had a policy of ‘dietetic only’ prescribing at discharge despite the lowest level of dietetic-endorsed prescribing. All of the hospitals with smaller numbers were unable to access electronic prescribing information and searched for patient cases by hand. We analysed the results including and excluding the small sample sizes and no difference was noted. These cases are therefore included. The audit tool was designed for use in adults and paediatrics and, despite the small sample size for paediatrics, these cases are also included, as it was found that exclusion of these cases made no overall difference.

Table 2. Audit of NBS at discharge, analysis of assessment by profession (dietitian or other Health Care Professional (HCP)

| Hospital | Dietitian assessed (n) | Other HCP assessed | Total (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital A | 87% (80) | 13% (12) | 92 |

| Hospital B | 34% (16) | 66% (31) | 47 |

| Hospital C | 65% (26) | 35% (14) | 40 |

| Hospital D | 95% (19) | 5% (1) | 20 |

| Hospital E | 92% (12) | 8% (1) | 13 |

| Hospital F | 58% (7) | 42% (5) | 12 |

| 224218 adult6 paediatric |

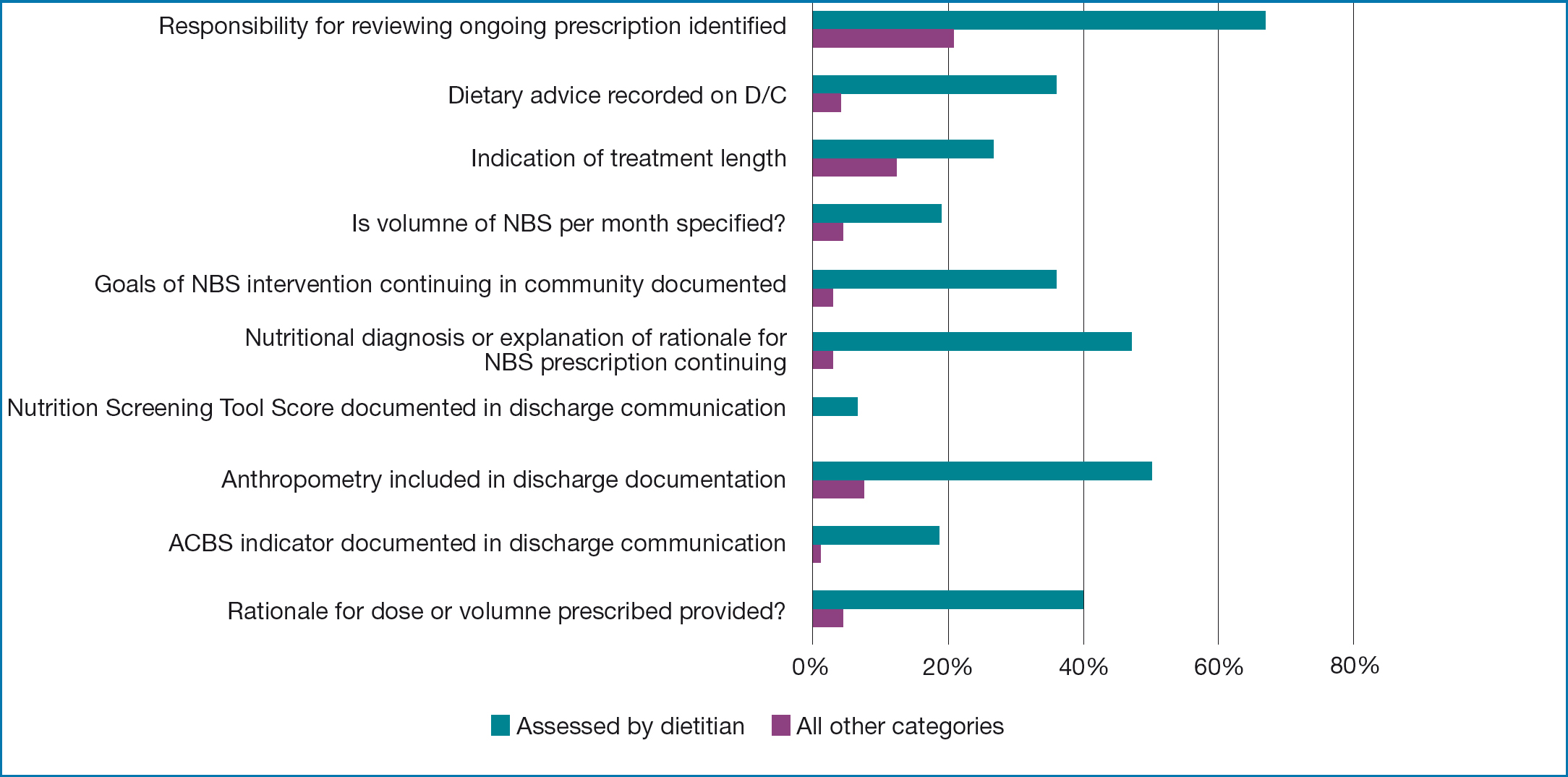

The audit also looked at quality criteria for appropriate prescribing of nutrition (Figure 2). This showed that dietitians provided considerably more information in support of their prescribing decisions than other healthcare professionals, but improvement is still needed.

Analysis of systems to support appropriate prescribing of NBS

Traditionally, many hospitals have excluded some or all NBS from pharmacy management and systems due to space and workforce limitations. Due to the low (or no) cost of NBS in hospitals the governance and systems to manage them appropriately are not prioritised highly. A typical drug chart is not especially well suited to NBS, however both POM and NBS are prescribed at NHS expense.

The Professional Records Standards Body guidance, Digital Medications Information Assurance, discusses digital communication of medication dose and timings between systems in all care settings (2019). NBS are included and there is significant scope to reduce errors in prescribing (for example transcribing errors relating to kcal/ml of similarly named products). There are limitations due to the complexity of prescribing approaches required for some items (such as IMD that require clinical evaluation or test results to decide on dose), therefore the dosage will continue to be entered manually rather than ‘translated’ between systems. Further consideration on how product or dosage based prescribing between settings, and actual or virtual medicinal products works for NBS is required as we move towards increased digitalised care.

In terms of patient safety, NBS are considered low risk when compared with POM. However, it is worth questioning if we adequately capture the harms of poor prescribing of NBS. Table 3 describes anecdotal reports of harm that is usually delayed, not directly attributable to NBS or captured by local incident reporting systems but without wider learning. To the best of our knowledge no audits or studies have identified the frequency of incorrect strength NBS (with associated cost implications) being selected on GP prescribing systems. However, because of the similarity in names of NBS with different strengths, audit is required.

Table 3 Anecdotal reports of harm related to appropriate prescribing of NBS

| Description | Impact |

|---|---|

| Patient prescribed incorrect strength of ONS (1kcal/ml), potential confusion regarding strength intended vs received and false reassurance that the problem is being treated | Delayed treatment of malnutrition with associated higher healthcare costsHigher cost of weaker strength ONS is a waste of NHS resources |

| Patient with a learning difficulty prescribed ONS with no review for > 5 years and excess weight gain of > 15kg | Reduced quality of lifeWaste of NHS resources |

| Tube fed patient prescribed a high cost fat supplement in addition to their high energy tube feed (1.5kcal/ml) due to weight loss. However incorrect tube feed (1kcal/ml) was prescribed originally | Delayed treatment of malnutrition with associated higher healthcare costsWaste of NHS resources |

| Infant IMD patient administered incorrect NBS | Brain damageLifelong care costs |

| Adult IMD patient given incorrect NBS | Metabolic decompensation and ITU admission |

Overall, analysis of the data and systems to support appropriate prescribing of NBS show that achieving it can be highly challenging. Nevertheless, there are areas which are within our ability to change or influence.

Potential solutions to the challenges of achieving appropriate prescribing of NBS

Ensuring digital systems support appropriate prescribing of NBS

There is a significant opportunity to use digital technologies to improve patient care, appropriate prescribing, and reduce costs. Regionally we have produced guidance encouraging inclusion of NBS on all electronic prescribing systems. This allows for reportable metrics on ratios of dietetic: other HCP-led prescribing at discharge, malnutrition screening and the potential for improved sharing of information across the care interface. Innovative work in Bradford using SystemOne has also been undertaken to improve the assessment, triage and diagnosis process, patient experience, care pathway and appropriateness of product choice for both malnourished patients (and recognised by SystemOne and PresQIPP) and infants presenting with suspected cow's milk allergy (South West Essex, pilot). Whether it is in a local hospital utilising e-prescribing controls to limit the risk that products are inappropriately continued in community when no longer justified, or a CCG building pathways on GP systems to improve quality and save money, there are examples that we can share and promote to encourage implementation.

‘Everyone responsible for prescribing NBS should do so appropriately, but lack of clarity and consensus about where that responsibility should ideally sit is likely to be contributing to the current financial challenge’

Education of the workforce

We undertook a regional survey (n=76) on ‘understanding the education needs of NHS dietitians on nutritional prescribing’. This demonstrated that the profession is keen for greater education on the principles and processes of appropriate prescribing. The development of online training to meet this need is underway. It is funded by and will be available free of charge to members of the British Dietetic Association (83% of the dietetic workforce are members). Consideration of how to reach all healthcare professionals (and administrative staff) who request, initiate, review or process and manage NBS across the healthcare economy is also needed.

There are a number of other strategies underway to improve education of dietitians and doctors on prescribing and nutrition that will take time to show the benefits. In the interim, promoting audit of prescribing of nutrition across the profession and encouraging Continuing Professional Development in these areas are activities that can be undertaken by individual HCP and teams. Resources detailing quality criteria for appropriate nutritional prescribing are widely available.

Resourcing the right workforce

Clearly everyone responsible for prescribing NBS should do so appropriately, but lack of clarity and consensus about where that responsibility should ideally sit is likely to be contributing to the current financial challenge. Change is underway in primary care, with the establishment and commissioning of practice-based pharmacists and physiotherapists as part of the creation of Primary Care Networks. Research is currently underway to evaluate the equivalent role in dietetics. Utilising the dietetic workforce to manage prescribing of nutrition would require a change in the law to allow independent prescribing rights for dietitians (either specifically for NBS, or unrestricted). Clarity about the legality of off-script models is also desirable, although this model is recognised to have the significant disadvantage of requiring significant investment in de novo establishment of an entire local supply chain and associated clinical and financial management and governance arrangements to support it. However this model, which aligns financial and professional management, should not be discounted.

An alternative to utilising the dietetic workforce to oversee prescribing is further training for GPs, nurses or pharmacists (including technicians). Anecdotal reports vary in success, with workforce challenges frequently cited as a barrier. Triage and management protocols, which identify straightforward inappropriate prescribing can be implemented with dietetic support and supervision. Without adequately detailed protocols, training and dietetic oversight, problems have been reported including lack of confidence in making changes or, conversely, making changes which are inappropriate with associated harm to patients and management challenges. Overall there is a need to evaluate and publish work in this area, to establish effective approaches that ensure the principles of medicines optimisation are used, outcomes and cost avoidance or savings are fully evidenced. Regardless of local approaches, the relative costs of training and employing any new workforce must be considered. GPs and pharmacists are more expensive to train and are usually higher banded than a majority of dietitians. The Interim NHS People Plan (NHS England, 2019a) identifies that ‘it has proved difficult to ensure we have the right numbers of staff with the right skills in the right place to meet patient need’ and notes a ‘lack of alignment between workforce, service and financial planning at national and local levels’. This is very much echoed by the current challenges in managing prescription of NBS. Ensuring an appropriate skill mix to deliver optimal patient care in the community and manage the costs of prescribing of NBS, and further discussion of how this can be achieved is essential.

Developing our thinking about the value of health promotion and supply of NBS on prescription

The NHS Long Term Plan emphasises the need to improve prevention and reduce health inequalities, although it does not specifically identify malnutrition, it does highlight the need to support ageing well. A key part of this is to highlight the importance of maintaining weight, eating nourishing foods and avoiding frailty (Volkert et al, 2018), yet there is an inconsistent approach to health promotion in this area. An example where this approach has been adopted is Eat Well Age Well in Scotland. Public Health and social prescribing can support improved nutrition if patients have access to or are referred to community opportunities that support social eating and increase resilience to overcoming nutritional vulnerabilities (Public Health England, 2017). Without greater awareness of the importance of weight maintenance in older age many people continue to focus on the avoidance of weight gain that is widespread in our obesogenic era (So, 2019). With a public health led approach to prevention of malnutrition in older age, we could expect to see a reduction in malnutrition and frailty prevalence and its associated higher healthcare costs, and a reduced need to prescribe ONS. Although beyond the scope of support with NBS, consideration of the value of vitamin D fortification would potentially reduce the need to prescribe colecalciferol, was identified as a research recommendation (Public Health England, 2016).

Using an NHS Rightcare approach to understand ONS prescribing suggests that there is scope for improving value to individuals and systems. Suboptimal care in nutritional support is currently seen in two groups of people: unidentified malnourished patients and those diagnosed as malnourished whose main or only care is the prescription of ONS (frequently without ongoing review). Optimal care includes prevention, early identification of established malnutrition, a full nutritional care process with or without nutrition support on prescription, and (usage) reviews. The cost of the workforce needed to review patients is neutral or may be more than offset by savings, if cost effective prescribing choices are made and duration of prescription is optimised. We therefore need to question which we value most, the current system or one which provides treatment for a greater number of patients. Debate in this area is often reduced to a false dichotomy of ‘food first’ or prescribed ONS. Further high-quality, independent, research is needed to redress the imbalance between the number of randomised control trials comparing ONS with ‘food first/standard care’, and to elucidate differences in disease, healthcare encounter, quality of life, length of treatment and other relevant outcomes (Baldwin 2018). The quality of food based nutrition support also needs careful consideration as comparing very basic advice based on adding calories with a comprehensive approach is problematic. Difficult questions about the current evidence base, prescribing choices and perceptions of value need to be asked in order to develop a culture of safe, sustainable cost-effective and affordable prescribing of nutrition.

Conclusion

There are significant challenges to be overcome if we are to consistently achieve appropriate prescribing of nutrition as evidenced by Prescribing Cost Analysis, audit and analysis of the systems and workforce. The NHS can adopt a number of approaches to make prescribing of nutrition more appropriate but ensuring the alignment of finances, appropriately skilled appropriately skilled and resourced workforce, with supporting digital systems, will be key.

Key Points

- There are numerous challenges in delivering appropriate prescribing of NBS at scale: workforce, procurement and increasing costs

- Rates of dietetic led assessment of prescribing at discharge are highly variable and correlate with staffing levels but not policy

- Various approaches can be utilised to improve prescribing and value, including public health, focusing on primary care workforce development and utilising digital systems.

CPD reflective questions

- How do you ensure that your prescribing choices are both clinically and cost effective to support affordability per the whole health economy?

- When reviewing a patient's nutritional prescription, how would you decide if it was within your professional competency to change a product requested or prescribed by someone else, or if you needed to work with the patient or seek advice from another HCP?

- What can you do to support a culture of safety and sustainability for nutritional prescribing?