Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a term that covers ulcerative colitis (UC), Crohn’s disease (CD) and IBD-unclassified (when the disease is not definitively UC or CD). Corticosteroids, such as prednisolone and budesonide, are regularly used in the treatment of IBD. Their mechanism of action is to suppress the inflammatory response that causes IBD symptoms.

Oral prednisolone is recommended as a treatment for exacerbations of moderate-to-severe UC or when 5-aminosalicylate (5-ASA) preparations have been ineffective or not tolerated (Harbord et al, 2017; Ko et al, 2019; Lamb et al, 2019). Prednisolone is similarly indicated for colonic CD or as an alternative to budesonide for inflammatory small bowel CD (Lamb et al, 2019). Prednisolone is rapidly effective at controlling symptoms in a majority of patients (Lennard-Jones et al, 1960; Truelove et al, 1962; Benchimol et al, 2008; Ford et al, 2011). Patients have reported clinical improvements in symptoms at 2 weeks following initiation in a prospective clinical trial (Rhodes et al, 2008). However, prednisolone is not effective at maintaining remission of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in the longer term when compared with placebo (Lennard-Jones et al, 1965). The use of prednisolone is also associated with significant side effects (including acne, insomnia, mood disturbance, diabetes and acid reflux), even with short-term use (Baron et al, 1962; Ford et al, 2011).

Following induction of remission, additional medications, such as thiopurines, methotrexate or biologic treatments, are used to maintain long-term clinical remission (Lamb et al, 2019; Feuerstein et al, 2020). Unfortunately, some of these medications can be slower to take effect and require significant screening tests prior to initiation to ensure patient safety (Lamb et al, 2019). Therefore, ensuring an efficiently managed transition on to these medications is important. Patients who do not receive treatment or do not respond adequately to treatment are at risk of deterioration (Jangi et al, 2020; Ungaro et al, 2020; Yoon et al, 2020). This increases the risk of hospital admission, as well as the need for more aggressive treatment or even for surgical intervention.

The IBD clinical nurse specialist (CNS) team is central to the care of IBD patients at our secondary care centre, in keeping with national recommendations (Kapasi et al, 2020). All outpatient clinic correspondence and endoscopy reports pertaining to IBD patients are copied to them. The CNS team maintains a registry of all patients using biologic medications, thiopurines and methotrexate. These registries allow the team to supervise drug monitoring, provide prescriptions as required and liaise with home-treatment services and the hospital infusion suite. The IBD CNS team also runs a helpline service for patients to call when experiencing flares of their IBD, chasing results or to making other enquiries regarding their IBD care.

The Toronto consensus for the management of non-hospitalised UC includes a recommendation for early evaluation at 2 weeks, for all patients with UC who are prescribed corticosteroids (Bressler et al, 2015). Furthermore, the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) guidance recognises that prolonged courses of corticosteroids when response is not achieved have a diminishing chance of leading to remission (Lamb et al, 2019). Given the clinical priority to achieve disease remission and significant prerequisites to initiation of maintenance therapy, this has the potential to be a high-value intervention.

Background

A system for evaluation of patients starting corticosteroids was established at the start of March 2020 by the IBD CNS team at the Dudley Group NHS Foundation Trust. This followed a route-cause analysis, in which a patient who did not respond to corticosteroids, and did not contact the team, required a colectomy. This system was established in addition to the usual CNS roles. All patients prescribed corticosteroids are contacted by telephone 2 weeks after initiation. A member of the IBD CNS team is then able to assess the patient based on their symptoms to determine if they are clinically improving in response to the corticosteroids. This is done following a treat-to-target approach (Agrawal and Colombel, 2019), ensuring that each patient has an individualised management plan. Response is not guided by a single scoring system but through taking a history including general wellbeing, number of bowel motions per day, the presence of blood and abdominal pain. If the trend in symptoms is not clear, the initial patient documentation from the time of prescription can also be reviewed.

In tandem with this, the team is able to check concomitant medication use, including Adcal (Kyowa Kirin) and 5-ASAs. Screening blood tests for maintenance therapy (including methotrexate, thiopurines and biologic drugs) can be confirmed to ensure that drugs are started or optimised as efficiently as possible. Adverse effects from the corticosteroids are sought, and any other pertinent aspects of treatment are discussed.

The role of the IBD CNS team can also be explained if required, along with details of the helpline, including how the patient can access help if their symptoms return. Should patients find that their symptoms are deteriorating, they then have access to the CNS team so that treatment can be escalated rapidly without the involvement of primary care teams or unplanned hospital attendances. It is also an important opportunity for patients to ask questions, as many of these patients have been newly diagnosed with IBD. Each telephone call requires approximately 20 minutes to complete, including any required documentation.

Aims

The IBD CNS team implemented a system of early evaluation for all IBD patients receiving a new course of corticosteroids. The aim of this study was to assess the service provided and identify potential benefits for patients who are started on corticosteroids. At present, there is no published evidence to support this practice.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study describes outcomes identified in prospective audit of the new early evaluation service and compares them with a retrospective control group. This study is reported in concordance with the STROBE guidelines.

Outcome measures included hospital admission within 6 months of corticosteroid prescription, surgery within 6 months of prescription and surgery within 1 year of prescription. A post-hoc subgroup analysis was undertaken for comparing admission within 6 months of corticosteroid prescription in UC patients only between groups.

Additional outcome variables available from the prospective data set included Adcal prescription, 5-ASA use and drug education. Data were also collected on whether screening for biologics or thiopurines had been completed, as well as if results were requested but not yet complete. Data regarding these outcomes were not available in the cohort not receiving an early evaluation.

To collect data on patients receiving early evaluation, the IBD CNS team prospectively audited the new system of corticosteroid early evaluation between 1 March 2019 and 28 February 2020. All patients receiving early evaluation were included. Information was recorded at the time of the evaluation. Electronic records were subsequently audited at 3 and 6 months to identify outcomes and progress with treatment plans.

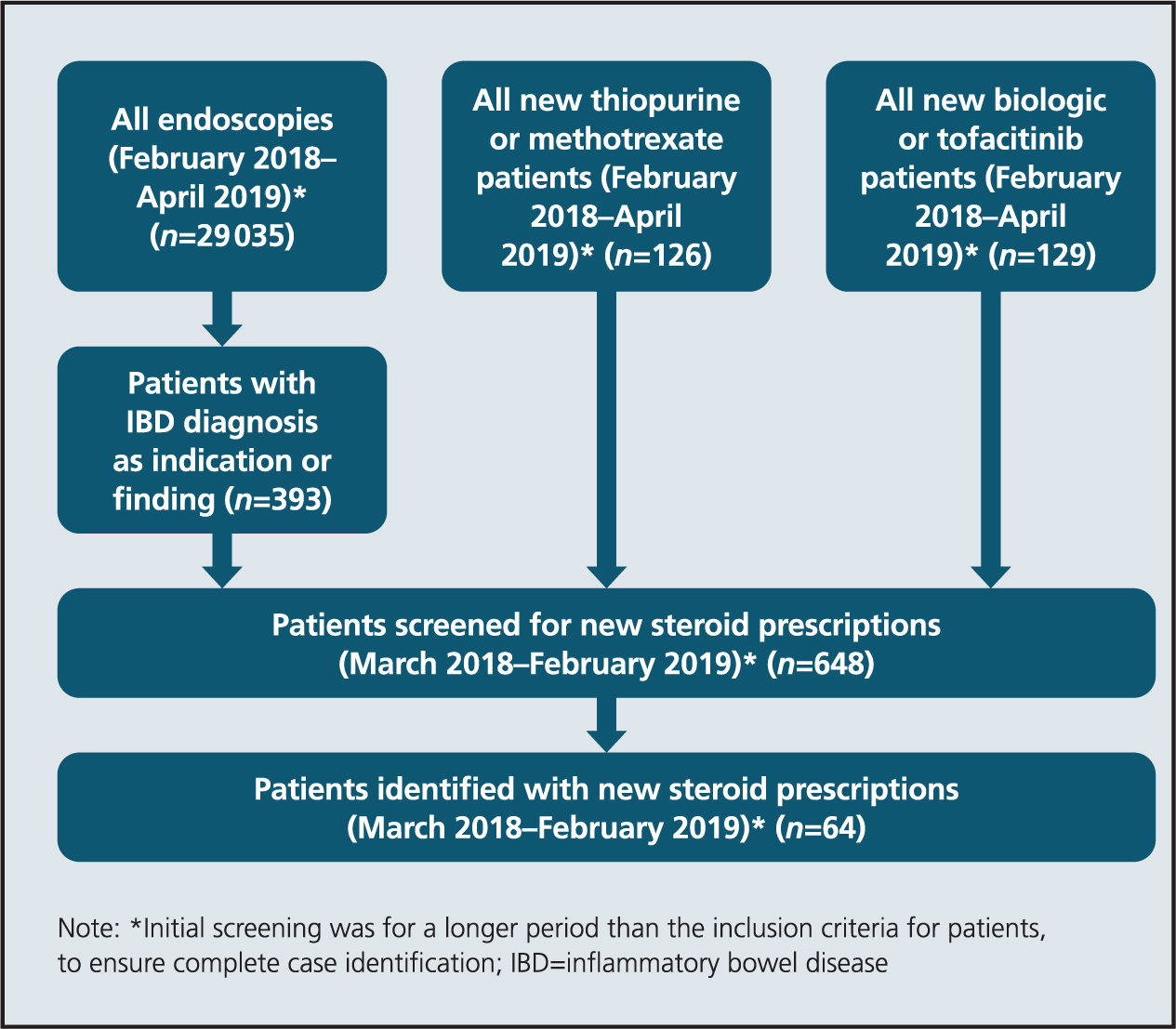

To collect data on patients not receiving early evaluation, a retrospective cohort of patients who had received a reducing course of prednisolone was identified between 1 March 2018 and 28 February 2019. This cohort was identified from three sources: all endoscopy reports including IBD as an indication or diagnosis, all patients starting thiopurine, methotrexate or biologic medications. Full details are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Retrospective case identification

Figure 1. Retrospective case identification

For selection criteria, patients prescribed corticosteroids as an inpatient were excluded, because their follow-up is potentially different compared with outpatient-initiated prescriptions. Patients later found to have a non-IBD diagnosis were also excluded.

Data regarding patient outcomes at 2 weeks were recorded at the time of early evaluation by the IBD CNS team as part of their routine documentation. All other variables were collected retrospectively from the hospital electronic patient records, including patient letters.

Demographic variables, including age at the time of corticosteroid prescription, sex and disease distribution, were collected for all patients. Medication use was recorded as those treatments the patient was already taking when prescribed corticosteroids.

Data are presented as numerical values and percentages or mean and standard deviation for continuous variables. Comparisons between cohorts were made using a chi-squared test or Student’s t-test for continuous data. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistics were undertaken in Stata version 15 (Statacorp, 2015).

Ethical considerations

As this study was evaluating a change in service provision, ethical approval was not required. Relevant approval for audit and service evaluation was granted by our organisation.

Results

Case identification

In total, 29 290 patients were screened from endoscopy results and patients starting thiopurines, methotrexate and biologic medications. Of those, 64 patients were identified as having been prescribed a reducing course of prednisolone between March 2018 and February 2019. Of patients, 79 were identified in the prospective audit data. However, three were excluded because they later identified as having an alternative diagnosis. A total of 76 patients were therefore included in the final early evaluation group.

Cohort demographics

In total, 140 patients were included in the study, of whom 76 (54.3%) received early evaluation telephone calls. The groups were demographically similar, with an average age of 46.8 years in the early evaluation group compared with 48.9 years in the unevaluated group. There were 32 (42.7%) and 24 (37.5%) women in each group respectively. A slightly lower proportion of UC patients were identified in the early evaluation group compared with the unevaluated group (54 (72.0%) vs. 56 (87.5%), p=0.0181). Descriptions of the cohorts can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Cohort demographics

| Feature | Early evaluation (n=76) | No early evaluation (n=64) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 46.8 (SD 18.0) | 48.9 (SD 17.3) | 0.485 | |

| Sex (female) | 32 (42.7%) | 24 (37.5%) | 0.580 | |

| Disease type (UC) | 54 (72.0%) | 56 (87.5%) | 0.018 | |

| Pancolitis (if UC) | 10 (18.5%) | 19 (33.9%) | 0.067 | |

| Colitis of unknown extent | 7 (9.2%) | 3 (4.7%) | 0.165 | |

| Disease location (if CD) | Ileal | 4 (19.0%) | 2 (25%) | 0.680 |

| Terminal-ileal | 13 (61.9%) | 3 (37.5%) | 0.295 | |

| Colonic | 15 (71.4%) | 4 (50%) | 0.361 | |

| Peri-anal | 2 (9.5%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0.783 | |

| Fistulising or structuring (if CD) | 7 (33.3%) | 4 (50%) | 0.361 | |

| Biologic use | 6 (8.0%) | 4 (6.25%) | 0.707 | |

| Thiopurine or methotrexate use | 16 (21.3%) | 14 (21.9%) | 0.906 | |

| Smoker | 9 (12%) | 3 (7.1%) | 0.124 | |

Medication use was similar between groups. Six (8.0%) patients in the early evaluation group were on biologics, compared with four (6.3%) in the unevaluated group. For methotrexate and thiopurine use, this was 16 (21.3%) and 14 (21.9%) respectively.

Benefits of early evaluation observed in the prospective cohort

At the time of the early evaluation telephone call, 41 patients (53.9%) had symptomatic improvement. In 27 (35.5%) of patients, it was identified that screening required for their planned maintenance therapy was incomplete, which could then be requested and chased up. Adcal was prescribed in 62 (81.6%) of patients, and 47 patients were on 5-ASA medications (61.8% of all patients, 87.0% of UC patients). Drug education was provided for all patients. All patients had the IBD helpline details following the early evaluation call, of whom 13 (17.1%) were given those contact details at the time of the call. Full detail of the outcomes from the early evaluation calls are given in Table 2.

Table 2. Benefits of follow-up

| Benefit | Early evaluation (n=76) | |

|---|---|---|

| Assessment of symptoms | Improved/corticosteroid responsive | 41 (53.9%) |

| Not improved | 35 (46.1%) | |

| Escalation screening | Complete | 35 (46.1%) |

| Completed for previous therapy | 9 (11.8%) | |

| Requested | 27 (35.5%) | |

| Incomplete/not required | 5 (6.6%) | |

| 5-ASA prescription | Yes | 47 (61.8%) |

| No | 5 (6.6%) | |

| Unable to tolerate/declined | 2 (2.6%) | |

| Crohn’s disease | 22 (28.9%) | |

| Adcal prescription | Yes | 62 (81.6%) |

| No | 13 (17.1%) | |

| Unknown | 1 (1.3%) | |

| Drug education | Yes | 76 (100%) |

| Adverse events to corticosteroid | Insomnia | 7 (9.2%) |

| Emotional disturbance | 5 (6.6%) | |

| Other | 1 (1.3%) | |

| Helpline details | Previously given | 63 (82.9%) |

| Given at time of call | 13 (17.1%) |

Objective outcome measures

Significantly fewer patients in the early evaluation group required admission to hospital in the 6 months after their course of corticosteroids, compared with those who did not have an early evaluation (7 (8.6%) vs 15 (23.4%), p=0.013).

A subgroup analysis was undertaken for admission for the UC patients only. Five (9.3%) of the early evaluation patients were admitted within 6 months, compared with 12 (21.4%) of the unevaluated group (p=0.0775). Full details of the objective measures are given in Table 3.

Table 3. Outcome measures

| Outcome measure | Early evaluation (n=76) | No early evaluation (n=64) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Admission within 6 months | 7 (8.6%) | 15 (23.4%) | 0.013 |

| Admission within 6 months (if UC) | 5 (9.3%) | 12 (21.4%) | 0.078 |

| Surgery within 6 months | 0 (0%) | 2 (3.1%) | 0.121 |

| Surgery within 1 year | 3 (3.9%) | 3 (4.7%) | 0.83 |

Discussion

In this study, fewer patients were admitted in the group that underwent early evaluation by telephone, 2 weeks after starting corticosteroids. This was over a period of 6 months following the initial corticosteroid prescription. Patients in the early evaluation group also benefitted from drug education and an additional review of screening tests that are a prerequisite of maintenance therapy. Almost one-in-five patients were provided with details of the helpline, because they did not have these previously.

This study suggests that the early evaluation is a valuable resource for patients. Patients prescribed steroid therapy are frequently newly diagnosed and receive a prescriptive without a face-to-face consultation with the IBD team. Therefore, the early evaluation is not only a chance for the clinical team to gather information, but also an opportunity to answer questions and begin building a therapeutic relationship with the patient.

Based on the results of this study, it is plausible that the early evaluation call led to a reduction in admissions in the following 6 months. A combination of ensuring a smooth transition to maintenance therapy; a helpline for patients to call rather than present to the hospital or their GP; and early identification of patients who are not responding to corticosteroids; all likely contributed to medium-term admission avoidance.

The new service was undertaken by members of the CNS team in addition to their regular duties. Taking 79 calls over a 1-year period will require approximately 30 minutes per week. However, many patients having an early evaluation telephone call who are awaiting escalation to new medications will need a conversation with the CNS team at some stage. Furthermore, patients who were not improving with the corticosteroids would likely have needed a greater time investment at a later date when they had become more unwell. Therefore, the time committed to extra telephone calls for the early evaluations is potentially time-neutral and may even be time-saving in some patients.

At the time of writing, there is no literature to report the value of an early intervention for patients prescribed corticosteroids for IBD. Several studies have looked at early evaluations by CNS teams after exacerbations of COPD (Smith et al, 1999; Cotton et al, 2000). These suggest that early CNS support was beneficial and was associated with reduced use of hospital services. Although the situation and chronic disease are different, this study supports the principle that early CNS support after initial treatment may be beneficial and can reduce hospital admission in keeping with the findings of the present study.

The historical comparison group is a potential source of bias, due to the comparison of prospective and retrospectively collected data. Specifically, case finding may also be incomplete, and comorbidities were not collected. However, extensive efforts were made to ensure that all patients were identified. Any patient with an exacerbation of their IBD would likely undergo endoscopic investigations and might then be started on a new maintenance therapy. All such patients would be identified in this study. However, considering that there were fewer CD patients in the retrospective cohort compared with the prospective cohort, it is possible that some patients may have been initiated on corticosteroids following a different investigation, such as an MRI scan of the small bowel, that highlighted active disease. To address this, a subgroup analysis of UC patients only was undertaken for the admission outcome. The groups were almost equal in number (54 vs 56), and the numerical reduction in hospital admissions remained (5 (9.3%) vs 12 (21.4%), p=0.078). The lack of statistical significance likely results from the small sample size, both in this particular analysis and in the wider study.

The COVID-19 pandemic introduces a potential source of bias into this study. Those patients given corticosteroids in the second half of the early evaluation period may have had a short period in the 6 months following their prescription when they felt uncomfortable attending hospital. This would artificially reduce the number of admissions in this group. However, considering that this only represented a 3-month window in the UK within the follow-up period, and a majority of admissions will have been unavoidable, this is unlikely to account for the almost three-fold increase in admissions in those without an early evaluation compared to those with. Furthermore, the pandemic may have led patients to stop their own immunosuppressant medications, which would instead be expected to precipitate additional admissions.

The early evaluation and unevaluated cohorts were similar in composition and baseline medication use. The exception to this is the proportion of cases with pan UC, which was 10 for early evaluation (18.5%) and 19 unevaluated (33.9%) (p=0.0667). It is also important to note that a larger group of the early evaluation group had not undergone full colonoscopy, that is seven (9.2%) vs three (4.7%), respectively. This is likely due to reduced endoscopy capacity due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Had all these patients undergone full colonoscopy, then it seems likely that the difference might have been reduced. The proportion of UC patients was also slightly lower?

CPD reflective questionsin the early evaluation group, potentially due to identification method, as identification from endoscopy reports is less likely to identify patients with CD being started on prednisolone if disease is localised to the small bowel or terminal ileum, compared with UC.

Conclusions

The early evaluation service implemented at our hospital provides tangible benefits to IBD patients. These appear to include a smoother transition to maintenance therapy, early identification of corticosteroid non-responders and an opportunity to develop a therapeutic relationship with new IBD patients, resulting in an association with reduced hospital admissions. Such services would benefit from further evaluation at different hospitals with larger numbers, outside of the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic, and they could be expanded to include patient-reported outcome measures. Despite these limitations, this study endorses the implementation of the early evaluation recommendation in the Toronto consensus for non-hospitalised patients.

CPD reflective questions

- How do you identify a patient who has poorly controlled inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)?

- What information would you share with a patient who is prescribed prednisolone for the first time?

- How could your IBD team improve the care given to patients receiving prednisolone?

- What are the benefits of early identification of a patient who is not responding adequately to prednisolone?