Prostate cancer is the most common non-cutaneous malignancy in men with more than 57 000 cases diagnosed in the UK each year. It is the second leading cause of cancer deaths (Kessel et al, 2021; Kinnaird et al, 2021). The majority of patients present with localised disease confined to the prostate, where the 5-year survival rate is up to 99%. In contrast, when metastatic disease develops, the 5-year survival rate decreases to 30%. Prostate cancer cells depend on the androgen hormone testosterone to grow and survive. The mainstay of treatment for metastatic castrate-sensitive prostate cancer has been androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), which controls the disease by lowering androgen levels. ADT was originally discovered by Higgins and Hodges in 1940. It is achieved using either surgical bilateral orchidectomy or medical gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (GnRH). The use of continous, rather than intermittent, ADT is recommended as data show this leads to a higher overall survival rate (Hussain et al, 2013). In the majority of cases of metastatic castrate-sensitive prostate cancer, tumours stop responding to androgen deprivation after 2–3 years, becoming castrate-resistant (Dela Rama and Pratz, 2015).

Castrate-sensitive metastatic prostate cancer (mCSPC) is prostate cancer that has spread beyond the prostate and can be controlled by ADT. Many patients develop advanced, recurrent or metastatic prostate cancer at a time when they never received or are no longer receiving ADT for localised disease in the adjuvant setting. In most of these cases, testosterone levels are higher than 50 ng/dl, whereas in castrate-resistant disease, testosterone levels are usually below 50 ng/dl. Traditionally, ADT alone was used in the treatment of patients with mCSPC. Significant improvement in overall and progression-free survival in mCSPC is now possible with the introduction of treatments earlier in the disease, such as novel hormonal therapies or docetaxel chemotherapy in combination with androgen deprivation therapy (Kessel et al, 2021; Hall et al, 2020; Laccetti et al, 2020). Current treatment by the NHS for hormone-sensitive metastatic prostate cancer is ADT alone or docetaxel plus prednisolone with ADT. In July 2021, NICE (2021) approved the use of enzalutamide plus ADT in mCSPC, providing patients with another treatment option.

Treatment of mCSPC changed in 2015, as a result of a number of large randomised phase 3 studies demonstrated improved survival with the addition of novel hormonal therapies or docetaxel to ADT. Three phase 3 trials looked at the addition of docetaxel to ADT in the mCSPC setting: CHAARTED 3805, STAMPEDE and GETUG-AFU-15, with both STAMPEDE and CHAARTED showing an improvement in overall survival (OS) compared to ADT alone. A meta-analysis of these three trials demonstrated that the addition of docetaxel to ADT resulted in improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) and OS, particularly in patients with high-volume disease (Hahn et al, 2018; Sathianathen et al, 2019). Current guidelines recommend docetaxel in patients with high-volume disease and state that the benefit may be less certain in patients with low-volume disease (NICE, 2021).

The treatment of prostate cancer progressed further in 2018 when three novel hormonal therapies, abiraterone, enzalutamide and apalutamide, received Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for the treatment of patients with mCSPC. The addition of abiraterone to ADT was evaluated in two large clinical phase 3 trials, LATTITUDE and STAMPEDE, with both trials demonstrating a reduction in all-cause mortality with the addition of abiraterone at 5 years.

The phase 3 ENZAMET trial evaluated the addition of enzalutamide to ADT. The ENZAMET trial randomly assigned 1125 men with mCSPC to ADT plus enzalutamide 160 mg daily or ADT plus a standard nonsteroidal antiandrogen. Patients were allowed to have docetaxel treatment (75 mg/m2) every 3 weeks for up to 6 cycles. The 3-year OS was 80% in the enzalutamide arm compared to 72% in the standard care group. The receipt of early docetaxel did not result in improvement in clinical PFS or OS but did cause more toxicities. Enzalutamide demonstrated significantly better OS and longer biochemical and clinical PFS (Davis et al, 2019). In the ARCHES trial, 1150 men were randomly assigned to ADT plus enzalutamide verse ADT with placebo. The enzalutamide arm was associated with significant improvement in radiologic disease-free progression, time to prostate-specific antigen progression and time to initiation of new antineoplastic treatment (Armstrong et al, 2019). Recently updated results from the ARCHES trial in the European Society of Medical Oncology (2021) demonstrated a significant improvement in OS with the addition of enzalutamide to ADT (Armstrong et al, 2021).

Apalutamide was evaluated in the phase 3 TITAN study, which compared its addition to ADT versus ADT with placebo. The combination resulted in a 33% lower risk of death and a 52% lower risk of radiographic progression or death at 24 months (Chi et al, 2019).

The optimum treatment choice using these three agents has not been established. A recent meta-analysis of 7287 patients in seven randomised trials demonstrated the largest OS benefit was seen in abiraterone and apalutamide, while enzalutamide was associated with the largest radiographic PFS benefit with a longer need for follow-up evaluation of benefit. Docetaxel was associated with the highest risk of serious adverse effects (Wang et al, 2021). Sathianathen et al (2019) published a metanaalysis looking at these four treatments and concluded that all four agents improved OS compared to ADT alone. Additionaly, there was no statistical difference between the agent concerning OS. However, Ferro et (2021) concluded that androgen receptor-targeted agents may provide improved overall survival when compared to docetaxel. In 2021, the NICE approved the use of enzalutamide in the treatment of mCSPC based on the two randomised trials, ENZAMET and ARCHES, which demonstrated a benefit over ADT alone with the addition of enzalutamide.

The choice of treatment used is dependent on disease extent, potential toxicities, duration of therapy, comorbidities, performance status, age and patient preference, as well as cost and reimbursement (Laccetti et al, 2020; Olivier et al, 2021). Docetaxel chemotherapy is administered every 3 weeks for 6 cycles but can have significant toxicities, including febrile neutropenia and peripheral neuropathy. The use of novel hormonal therapies is continuous for months or possibly years but has fewer systemic side effects when compared to docetaxel. Each of these agents has its own specific side effects. Abiraterone causes elevation of liver enzymes, fluid retention and cardiovascular events, and requires concomitant administration of oral steroids. Enzalutamide can cause cognitive impairment, seizure, fractures, falls and hypertension, while apalutamide can cause hypertension and rash (Kessel et al, 2021). Understanding these treatment-related toxicities is essential when deciding on the best treatment option for patients (Hall et al, 2020).

Pharmacology of enzalutamide

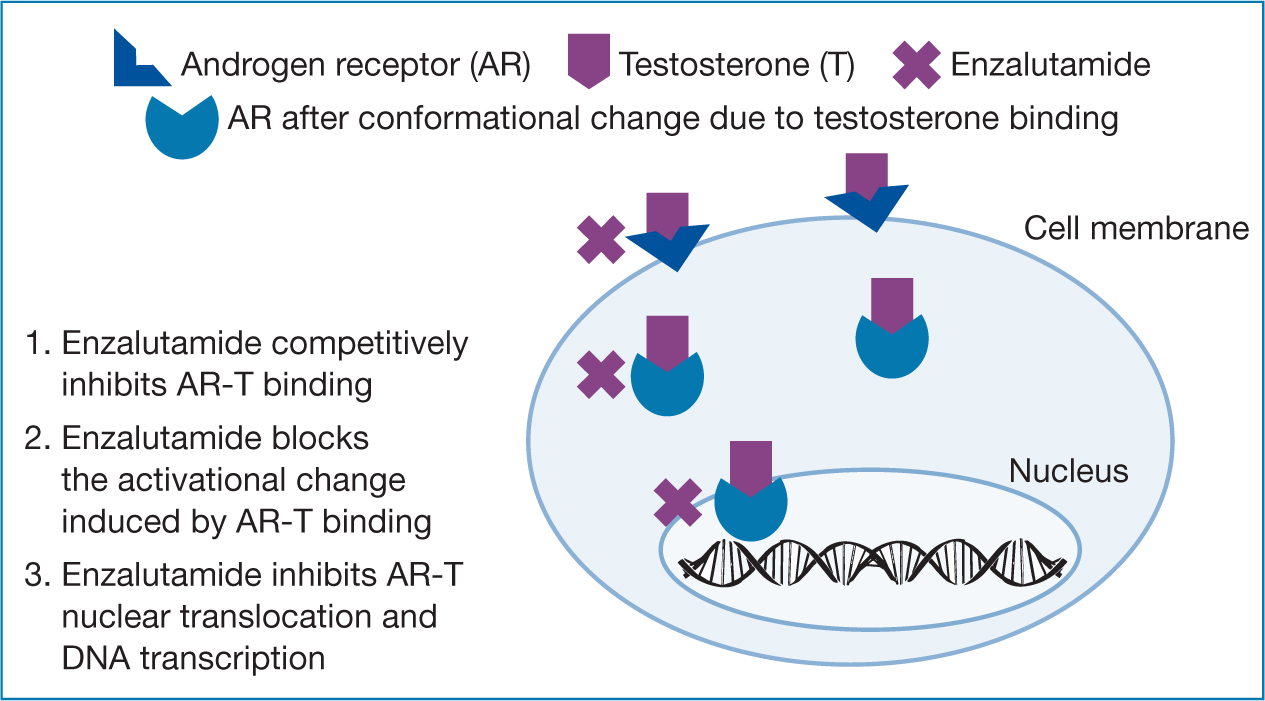

Enzalutamide is an orally administered, small-molecule inhibitor of the androgen receptors and is designed to overcome acquired resistance to first-generation nonsteroidal antiandrogens, including bicalutamide, nilutamide and flutamide. Enzalutamide acts as an inhibitor of androgen receptors, preventing binding of androgen and inhibiting androgen nuclear translocation and DNA interaction (Figure 1). It has a high affinity for the androgen receptors compared to first-generation antagonists (Hahn et al, 2018; Laccetti et al, 2020). Enzalutamide also decreases proliferation and induces cell death of prostate cancer cells. It is well absorbed following oral administration and is extensively metabolised by the liver. The half-life of enzalutamide is 5.8 days.

It should be used with caution in patients with a history of seizures, underlying brain pathology, cerebrovascular accident, transient ischemic attack with the past 12 months and brain metastases. The most common side effects include headache, weakness, hot flushes, loss of libido, diarrhoea, arthralgia and musculoskeletal pain. Less common side effects include cognitive impairment, falls, seizures, fractures, cardiovascular events and hypertension (Sternberg et al, 2020). Fatigue, falls and cognitive impairment was seen more in elderly patients, who account for a high percentage of prostate cancer patients, and can have a detrimental effect on quality of life and safety (Laccetti et al, 2020). Contraindications to enzalutamide include underlying seizure disorder, poorly controlled hypertension, clinically significant fatigue and cognitive impairment. It should be used with caution in patients over the age of 75 years, particularly because of the risk of falls, and patients with a history or risk of QT-interval prolongation (Laccetti et al, 2020; Joint Formulary Committee, 2022).

Dosing and administration

Enzalutamide is an oral treatment with a starting dose of 160 mg daily. Each capsule contains a 40mg dose and patients are advised to take four capsules, once daily by swallowing them whole with a glass of water. Patients should take the medication at the same time every day. If the patient misses their daily dose, treatment should resume the following day at their usual daily dose. If a patient experiences a ≥ grade 3 toxicity, the dose should be withheld for a week or until symptoms improve to ≤ grade 2 then resume at the same or reduced dose or discontinuation depending on the toxicity (European Medicine Agency, 2022).

Patients receiving enzalutamide should also receive a gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogue concurrently or should have had bilateral orchiectomy (Davis, 2019). The potential for drug-to-drug interactions for patients taking enzalutamide is considerable and requires careful monitoring before treatment initiation and throughout the treatment (Morgans et al, 2021).

Enzalutamide interacts with cytochrome P450, CYP2C8 and CYP3A4 inhibitors, which increase its plasma levels and risk of toxicities. Strong CYP3A4 inducers, including carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin and rifampin, may decrease levels and affect response. St John's wort should be avoided as it may decrease levels and response.

The prescribing information recommends that prescribers avoid simultaneous use or exercise caution if using enzalutamide with medications that are strongly affected by these metabolising enzymes. If concurrent use of potent inhibitors of CYP2C8 is unavoidable the dose of enzalutamide should be reduced to 80 mg daily (Joint Formulary Committee, 2022). It is recommended to consult with the product summary of product characteristics for comprehensive interactions and guidance (Astellas, 2019). The BNF (Joint Formulary Committee, 2022) has a comprehensive list of medications that can interact with enzalutamide available on its website and this should be consulted by prescribers and those caring for patients on enzalutamide.

The nursing assessment of patients on enzalutamide should include monitoring for seizures, hypersensitivity and for signs and symptoms of heart failure, including chest pain or tightness, fainting and dyspnoea. Patients should also be assessed for risk of falls before initiating treatment periodically during treatment.

Specific side effects

The main side effects of androgen receptor inhibitors include cardiovascular toxicities, metabolic syndrome, sexual dysfunction, bone changes, central nervous system toxicities and fatigue.

Fatigue

Fatigue is the most common side effect related to enzalutamide treatment, occurring in up to 37% of patients (dela Rama and Pratz, 2015; Armstrong et al, 2019; Davis et al, 2019). Fatigue can be a result of lower testosterone levels in patients or a side effect of the therapy. It is frequently an under-recognised adverse event and has been consistently described in the literature as enhancing in terms of severity, interference, and duration over the course of treatment.

It has been demonstrated that a greater number of baseline comorbidities and a higher baseline Gleason score correlate with worsened fatigue in men receiving treatment (Nelson et al, 2016). Patients receiving enzalutamide have a higher risk of all-grade fatigue. Assessment, grading and monitoring of fatigue using validated and reliable tools, for example the Cancer Fatigue Scale, is essential throughout treatment. It is important to educate patients on this side effect and its management. Patients should be advised regarding exercise, sleep, nutrition, stress management and cognitive behavioural therapy, which may help to alleviate symptoms (dela Rama and Pratz, 2015). Grade 3/4 fatigue may require dose interruption or reduction in dosage (Astellas, 2019; Joint Formulary Committee, 2022).

Cardiovascular effects

Cardiovascular toxicities, including arterial hypertension, ventricular arrhythmias, atrial fibrillation and myocardial infarction, have been associated with androgen receptor-targeted therapies. Abiraterone is associated with all-grade and high-grade cardiovascular toxicity, but not with all-grade or high-grade fatigue. Arterial hypertension is twice as common with enzalutamide and ADT compared to ADT alone (Morgans, 2021; Sternberg et al, 2020). Baseline cardiac assessment is recommended prior to commencement of therapy and the patient should have their blood pressure regularly monitored throughout their treatment to diagnose new events. The cardiology teams input may be required if severe toxicities develop. The oncology nurse prescriber should monitor for signs and symptoms of ischemic heart disease and ensure effective management of cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes or dyslipidemia. Enzalutamide should be discontinued if the patient develops grade 3–4 ischemic heart disease (Astella, 2018; Morgans, 2021; Joint Formulary Committee, 2022).

Metabolic syndrome

Metabolic changes associated with ADT include hyperglycaemia, increase in body mass, loss of muscle mass and fatigue, which may have a major impact on a patient's quality of life, self-care abilities, and psychological status. There is a significant correlation between body mass index, and increased inflammation and tumour growth. Patients on enzalutamide have been shown to have a shorter OS and PFS if they develop metabolic syndrome. Baseline blood glucose and body mass index should be assessed prior to treatment and regularly monitored throughout treatment. Patients should be advised to modify their lifestyle by increasing their level of exercise to 30 minutes each day, adopting a healthy diet and smoking cessation (Morgans, 2021).

Sexual dysfunction

Sexual dysfunction is a very common side effect of prostate cancer treatments and has a significant effect on patients' quality of life. The low serum testosterone levels caused by ADT result in the majority of patients experiencing reduced desire and function and erectile dysfunction. Patients can also develop gynaecomastia and penile shrinkage. Androgen receptor inhibitors contribute to these side effects. Many patients highlight an unmet need in sexual dysfunction management. Management includes lifestyle changes, including smoking cessation and weight loss, psychosexual support and counselling, as well as erectile devices and medications, including phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors and alprostadil (Kinnaird et al, 2021).

Central nervous system toxicity

Newer androgen therapies can cross the blood–brain barrier (Ryan et al, 2020). Enzalutamide is associated with a significant decrease in cognitive function and falls, especially in patients over the age of 75 years. It is also associated with increased risk of seizures; however, incidence is small, at 1% in the ENZAMET trial (Davis et al, 2019).

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) has been reported in patients receiving enzalutamide. It is a neurological disorder in which patients present with rapidly evolving symptoms such as headaches, seizures, lethargy, confusion and blindness. The diagnosis is confirmed on MRI and enzalutamide should be discontinued immediately in patients who develop it (Corona, 2015). In combined data of four randomised trials, falls occurred in 11% of patients treated with enzalutamide versus 4% in the placebo group. Fractures occurred in 10% of patients treated enzalutamide compared to 4% in the placebo group (FDA, 2019).

Cognitive impairment has the potential to reduce the patient's ability to make an informed decision about their management. It can also affect their social, psychological and physical wellbeing and thereby affect their quality of life (Ryan et al, 2020). A patient's cognitive function and risk of seizure and falls should be assessed prior to the initiation of therapy and monitored throughout treatment (dela Rama and Pratz, 2015). Referral to specialised teams may be required if deterioration is discovered in the patient's cognitive function (Ryan, 2020). Patients and their caregivers should be educated regarding the potential for seizures and cognitive decline. Patients who develop seizures should have their treatment discontinued permanently (Graff et al, 2016; Khalaf et al, 2019).

Nursing considerations

Nurses have a significant role in the care and management of mCSPC patients taking enzalutamide. Patients are living longer and have to deal with the physical and psychological effects of their diagnosis and treatment (Kinnaird et al, 2021). They need to have a detailed understanding of the risk factors, side effects of treatment, complications from the disease and the disease trajectory. A nurse's role include prescribing within their scope of practice and local guidelines and policies (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2018), as well as providing patient and caregiver education, monitoring adherence and toxicities, assessing comorbidities and functional health status and managing drug interactions.

The code of professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses, midwives and nursing associates is structured around four themes: prioritise patients, practice effectively, preserve safety and promote professionalism and trust. These key principles provide nurses with a guide to the provision of the highest standards of care in nursing practice (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2018). Weeks et al (2016) found that non-medical prescribers can be as effective as doctors in aspects of prescribing, including adherence to treatment, overall satisfaction and patient quality of life.

Patients should have cardiac, bone, cognitive and metabolic assessments prior to, and throughout the treatment. Baseline tests should include full blood count, renal and liver profile, blood pressure and ECG in patients at risk of QT prolongation and INR for patients on warfarin. Blood tests should be repeated every 4 weeks or as clinically indicated. INR should be monitored weekly if the patient is on warfarin until a stable warfarin dose is established. Blood pressure and other cardiac monitoring should be carried out periodically and as clinically necessary. Patients without bone metastases should have a baseline bone mineral density scan prior to treatment and be assessed using the WHO FRAX tool. Disease monitoring should be in line with the patient's treatment plan and any other tests as directed by the supervising consultant.

A comprehensive examination of comorbidities and patient medications including prescription, over-the-counter and complementary medicines, as well as recreational drug use and performance status is essential to minimise and manage toxicities and interactions (Paterson and Nabi, 2016; Morgans, 2021; Olivier et al, 2021). Patient and family education should include written and oral instructions regarding administration, side effects and management of toxicities while taking enzalutamide. The importance of involving family caregivers, especially with elderly patients, is essential for ensuring compliance and continuity of care (Banna 2020). Initial education prior to the commencement of enzalutamide and ongoing monitoring has been linked to improved adherence in patients while poor adherence may decrease efficacy and impact survival (Zerillo et al, 2018; Banna et al, 2020).

Oncology nurses provide holistic care for patients working with members of the multidisciplinary team by addressing the biological, social, psychological and spiritual wellbeing of the patient. They should combine their expert knowledge, advanced practice, holistic assessment and advanced communication skills as part of the multidisciplinary team to improve the cancer patient experience (dela Rama and Pratz, 2015; Hand nee Davies, 2019). A multidisciplinary approach in the management of prostate cancer patients ensures safe and effective prescribing practice (Hand nee Davies, 2019). Comprehensive holistic assessment, monitoring and education throughout the treatment journey is essential in the provision of the highest standard of care. The use of validated assessment tools, for example, common terminology criteria for adverse events 2017 (CTCAE) allows for comprehensive assessment and grading of toxicities. The monitoring of potential treatment toxicities, especially cardiovascular, metabolic syndrome, bone health, falls risk, cognitive function and fatigue, will help to improve patients' quality of life. The early identification and management of toxicities can improve medication adherence (Zerillo et al, 2018). Nurses should actively educate their patients on lifestyle changes, including daily exercise, healthy diet, weight management and smoking cessation, which will help to minimise side effects and improve quality of life (Morgans, 2021; Olivier et al, 2021).

Conclusions

The treatment of mCSPC has evolved rapidly over the last 10 years with the introduction of chemotherapy and newer hormonal therapies earlier in disease progression. These therapies have been proven to prolong OS and PFS when used in conjunction with ADT, compared to when using ADT alone. These agents have different administration requirements and toxicity profiles and are suited to different cohorts of patients. Nurses have an important role in the management of prostate cancer patients through comprehensive assessment, monitoring and early intervention and management of toxicities.

Nurses must ensure their knowledge is up-to-date and must be committed to continued professional development to ensure the highest standard of care for their patients. With the growing use of oral therapies in the treatment of mCSPC, there is an urgent need to develop safe and effective systems to administer and manage these agents.