I – Immunisations

Since the discovery of the smallpox vaccine in the late 18th century, it is still estimated that 20% of deaths in children under 5 years of age are due to diseases that can be prevented by current licensed vaccines (Lahariya, 2016). There remain many vaccine misconceptions, usually triggered by misinformation or viewpoints from those active in ‘anti-vaccine’ movements (Holford et al, 2024). Parents who are hesitant to vaccinate their child may choose alternative schedules, or refuse vaccines, and may depend on homeopathic or naturopathic practice (Anderson, 2015), so it is important that healthcare professionals are well informed regarding immunisations (Davies et al, 2021).

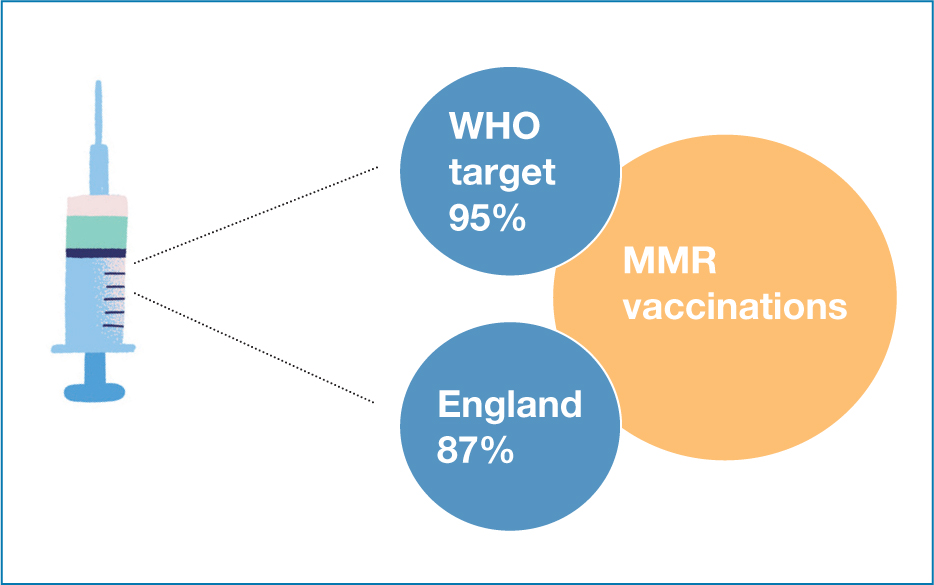

The measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine, given when a child is 1 year of age, and again at 3 years, 4 months of age (British Society for Immunology (BSI), 2023) has been the focus of safety concerns in recent years due to disproven theories associating the vaccine with autism. This has resulted in a decrease in the uptake of vaccines (see Figure 1), and an increase in the incidence of measles throughout Europe, although calls for vaccines to be mandatory may, conversely, harm public health policies (Kennedy, 2020).

Whooping cough cases are on the rise in the UK, also due to a decrease in vaccine uptake (GOV.UK, 2023a). Due to these dips in vaccine confidence, recent proposals have put forward the idea of targeting younger people, in the hope of building a new generation of well-informed adults with an accurate knowledge of vaccines (Burki, 2023). It is clear that vaccine development is not slowing down (Clutterbuck, 2015), which was demonstrated during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine commenced in 2008, initially targeting 12–13-year-old girls, and boys were added to the programme in 2019, with the introduction of single dose vaccines from September 2023 (GOV.UK, 2023b). However, recent surveys still demonstrate that around 10% of parents would not allow their child to have the vaccine (Waller et al, 2020). Prescribers must not forget that if they deem the child to be Gillick competent, and the child themselves wants the vaccine, then that child's rights need to be respected (Griffith, 2021) although, clearly, it is preferable to have discussions with the parents.

Prescribers themselves need to have accurate, up-to-date information regarding immunisations, and knowledge of current regimens is paramount (see: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/routine-childhood-immunisation-schedule).

Asking the child and parent or carer about their immunisation status is vital during history-taking; an answer of ‘up to date’ is not sufficient, as different immunisation programmes are in place for selected target groups. Particular focus needs to be given in emergency departments, as unvaccinated or overdue children may present more frequently, and evidence shows that questioning on immunisation status is poor (Nohavicka et al, 2013).

Adherence to the Royal Pharmaceutical Society Competency framework (RPS, 2021), with reference to competency 9.4 (‘Takes responsibility for own learning and continuing professional development relevant to the prescribing role’) is pertinent, as developments may progress for vaccinations for both respiratory syncytial virus and chicken pox (GOV.UK, 2023c; 2023d) in children.

The next article in the series will be L – Legal.