References

A–Z of prescribing for children

Abstract

This series focuses on aspects of prescribing for neonates, children and young people, from A–Z. Aspects of pharmacokinetics will be considered, alongside legal considerations, consent and medications in schools

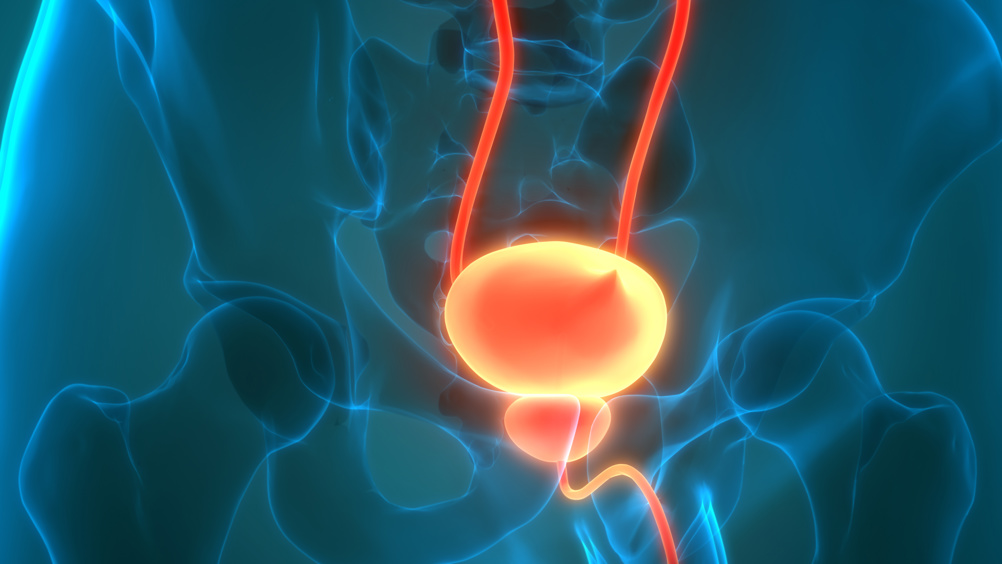

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are one of the most common bacterial infections seen in childhood. An understanding of the three categories of UTIs are useful for knowing the correct treatment and management (Tullus and Shaikh, 2020) (Table 1), and identifying the area affected also has an impact on treatment.

Bacteria is found in all UTI cases, with Escherichia coli (E. coli) detected in up to 90% of cases, originating from faecal flora, with vaginal flora also affected in girls. E.coli is a gram-negative bacillus, which is in the normal intestinal flora, causing intestinal and extra-intestinal disturbances.

Gram-negative bacteria show up as pink or red after gram testing. Gram testing (or staining) is used to differentiate between types of bacteria by looking at cell wall properties; gram-negative bacteria have thinner cell walls, typical of E. coli (Becerra et al, 2016).

Knowledge of the different antibiotics that are available is imperative, including those factoring in the type of UTI the patient presents with. Appropriate treatment is essential, but is challenging due to the increasing resistance to commonly prescribed antibiotics (e.g. amino-penicillins), and the increasing trend of multi-drug-resistant organisms that cause UTIs (Vazouras et al, 2020). Broad spectrum antibiotics increase the chances of covering and treat the causing pathogen, which results in the patient's recovery; yet, this does increase the overall expansion of antibiotic resistance (Diamant and Obolski, 2024). This has been demonstrated, for example, in Greece, where resistance to ampicillin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole has been cited as high as 51% and 29%, respectively (Vazouras et al, 2020). Therefore, antibiotic therapy should ideally be prescribed with a more narrow spectrum antibiotic, which can be based on local sensitivity patterns (Daley et al, 2020) and local antibiotic resistance data from Public Health England (NICE, 2018a).

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting Journal of Prescribing Practice and reading some of our peer-reviewed resources for prescribing professionals. To read more, please register today. You’ll enjoy the following great benefits:

What's included

-

Limited access to our clinical or professional articles

-

New content and clinical newsletter updates each month